Worcester is universally recognized as being home to the first Armenian community in the United States. Armenians have been coming to Worcester for nearly 150 years now. In the early years, Armenians predominantly came from the “golden plains” of Kharpert. Later arrivals came from Chemishgadzak, Kghi, and other nearby regions. They should not always be thought of as immigrants, as many simply came to work before returning to their hometowns.

One hundred years ago, the onset of the genocide created a great divide between those who were trapped in America and their loved ones in Armenia. While we all know the stories, and our own family histories, how many of us really take a moment to contemplate what that must have been like? If you are a parent, pretend for a moment that you are separated from your spouse and children without any hope of reuniting or even knowing what has become of them and the unspeakable horrors they are enduring. As a child of any age, imagine the loss of security a parent supplies and the lasting psychological trauma of witnessing the death of loved ones and the destruction of one’s home.

If you are able to stretch the limits of your imagination, then maybe you can begin to understand the magnitude of the crime that was committed against our people. It is not a crime that ends in a moment; rather, it is a crime that endures for a lifetime, and beyond.

On Sept. 14, 1909, Ohan Der Davidian arrived in New York City on the S.S. La Gascogne. Ohan was like so many Armenians coming to the United States. He was from Kharpert and traveling to Worcester. He was coming to join his brother Haroutiun. The passenger list also indicates the closest relative he had left behind was his wife, Turan Magarian.

What the passenger list does not indicate was that Turan was 6 months pregnant with their first child.

Ohan and Turan were married on Dec. 13, 1907, in Kharpert. Before traveling to far-off places to earn money, it was common practice at the time for young Armenian men not only to be married but also to have either children or a pregnant wife. Experience had shown that such requirements were necessary to ensure the return to the hometown of young men who represented the future of both family and community.

On Dec. 24, 1909, Turan gave birth to Vartanoush, sweet Rose. It would be 10 years before Ohan would see his daughter for the very first time.

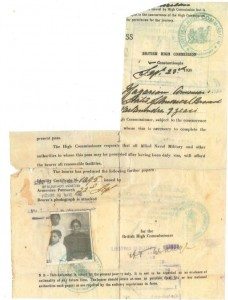

A fragment of a document issued by the British High Commission, along with a partial photograph, remains.

When Ohan left for the United States, Turan remained under the protection of her brother, Asadour Magarian. Asadour was a baker with his own wife and children. In 1915, Asadour escaped imprisonment and death by running through the countryside. Their experiences over the next three years are vague and uncertain. Turan and Rose spent some time in a camp, and it was Asadour who somehow rescued them. They escaped to Russia and spent four years there. Rose lost her hearing in one ear when a man slapped her so hard on the side of the head that her eardrum burst.

Asadour, Turan, and their families ultimately made it to Constantinople after the end of the war. A fragment of a document issued by the British High Commission, along with a partial photograph, remains. They then made their way from Constantinople to Marseille, France.

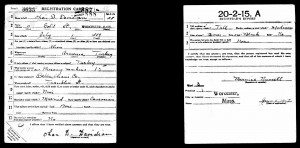

It is unknown whether they had any communication with Ohan during these years. Ohan’s World War I draft registration indicates he is married, but he states there is no one that is solely dependent on his support.

On Dec. 12, 1920, the entire surviving Magarian clan arrived in the United States on the S.S. Canada. Turan entered the country as the wife of Baghdasar Magarian of New Britain, Conn., while Asadour stated that Baghdasar was his brother. In truth, today no one knows exactly how Baghdasar was related to Turan and Asadour. By 1930, Baghdasar was living alone as a boarder in Connecticut, while the Magarian and Der Davidian families were in Worcester.

In the desperation of the times, it was common to misrepresent oneself to enter the country. Ohan had not yet become a citizen of the United States. My assumption is that Baghdasar, who had come to the United States in 1901, was a citizen and, thus, by using his name it was possible for “his family” to enter the country. I do not have proof of this, but it is a reasonable assumption to make based on many similar stories of immigration to the United States that I have documented.

Thus, finally in 1920, Rose and her mother Turan were reunited with Ohan. He met them as they disembarked the boat in Providence. Rose ran to her father’s outstretched open arms and, while the adults talked, he would not let her go.

Turan and Ohan would add another daughter, Mary, to their small family. Sadly, a son would die in childbirth. They lived out the rest of their lives in Worcester. Today, sweet Rose is the last known survivor of the Armenian Genocide in this special community.

At noon on Sat., April 18, the greater Worcester Armenian community will be commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide with a march down Main St. to Worcester City Hall. A tree planting and plaque dedication will also take place. Sheriff Peter Koutoujian, Congressman James McGovern, and Mayor Joseph Petty as well as other civic leaders will be in attendance to offer remarks. Following the ceremony, there will be an Ecumenical Service at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

***

The March begins at noon at Lincoln Tunnel at Salisbury St. (end of Main St.). For more information, readers may contact the Armenian Church of Our Saviour at (508) 756-2931; the Armenian Church of the Martyrs at (508) 753-7650, the Holy Trinity Armenian Apostolic Church at (508) 852-2414; or the Sp. Asdvadzadzin Armenian Apostolic Church of Whitinsville at (508) 234-3677.

The post The Last Survivor in the First Community appeared first on Armenian Weekly.