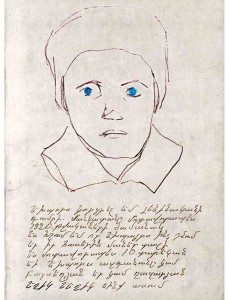

Last week, I received an email from a friend, asking that the Armenian Weekly publish a notice about a woman in Armenia searching for her older brother. The woman is 109 years old. She lost her brother around 1920. A photo of a drawing of a young boy was attached to the message.

When I saw those pools of blue where his pupils ought to be, I was floored. A simple sketch of a brother long lost erased the past 10 decades or so—and there it was: a river of blood, an orphanage, and a sister looking for her older brother. She used to call him “Yeghig-Yeghig.”

When I saw those pools of blue where his pupils ought to be, I was floored. A simple sketch of a brother long lost erased the past 10 decades or so—and there it was: a river of blood, an orphanage, and a sister looking for her older brother. She used to call him “Yeghig-Yeghig.”

It’s not every day that we publish a missing person’s alert, certainly not 100 years later. But here she is: Yepraksia Gevorgyan, a 109-year-old grandmother—a survivor of the Armenian Genocide—looking for a brother she lost almost a century ago.

She remembers when she was 10, riding high up on her brother’s shoulders… She remembers crossing the blood-red waters of the Araks River.

Fragments of memory frozen and transmitted through a couple of simple words violently hurl what’s pure and innocent into that horrific Disaster—that Crime that is beyond words and comprehension.

It was around 1920 when she lost him. They were separated at an orphanage in Alexandropol (now Gyumri); he was presumably adopted by a family who took him to the U.S.

“We used to call him, Yeghig-Yeghig,” she wrote beneath the sketch.

I looked from one blue stained pupil to the other, muttering “Yeghig-Yeghig” to myself.

And here is what’s perplexing yet fully understandable and beautifully human: Almost an entire century later, she is still hopeful. At 109, she is looking for her older brother.

The truth is, that sort of hope never really dies.

And here is what’s perplexing yet fully understandable and beautifully human: Almost an entire century later, she is still hopeful. At 109, she is looking for her older brother.

The truth is, that sort of hope never really dies.

There was a time when the Hairenik Weekly—our Armenian-language sister publication, founded in Boston in 1899—frequently ran notices like this in its pages. Survivors were looking for their immediate and distant relatives and friends.

I bring out the 1920 issues of the paper and begin flipping through the pages…

Thurs., April 1, 1920

“I am looking for my brother Bedros Koorajian from the village of Shiro Keferdiz in Kharpert. He was in Alexandropol in the Spring of 1918. If you have any information, please contact K. Koorajian…”

“I am looking for my sisters Yeghsa and Anna Taboian from the village of Mour in Kharpert. A few years ago they were in the Garin and Erzinga area. If you have any information, please contact Hovhannes Taboian…”

“I am looking for my wife Yelmo, and my children Baydzar, Mkhitar, and Mariam Derderian from the village of Gamis in Sepasdia. I promise a reward of $25 to anyone with information. Lousarev Derderian…”

“I am looking for my wife Elmas, my children Siranoush and Suren Mergerian, natives of Sepasdia. I haven’t received any news from them since the deportation. For anyone who knows where they are or if they are alive, I promise them a decent reward. Hovagim K. Mergerian…”

There are 11 such listings on that date, each followed by a one-sentence appeal: “We ask newspapers abroad to reprint this.”

The Hairenik Weekly was a daily newspaper back then. Day after day, the entries continue.

And I look back at Yeghig-Yeghig—his features sketched the way Yepraksia remembers him, and his blue-blue eyes like the waters of Lake Van on that sun-kissed day last May, when a group of us hiked up to remote churches and monasteries, all marked by a glaring, frightful absence…

One hundred years, and the past is so chillingly close.

The post A Century through a Boy’s Eyes appeared first on Armenian Weekly.