The Story of Two Armenian Midwives

Below is the text of a lecture delivered by scholar and former Armenian Weekly editor Khatchig Mouradian at the first commemoration of the Armenian Genocide in Aintab, held on March 21. The talk was delivered in Turkish. The commemoration was organized by the Greens and the Left Party of the Future. Party spokesperson Sevil Turan, writer Attila Tuygan from Istanbul, and translator Murat Uçanar also spoke. Celal Deniz delivered the opening remarks.

I want to tell you a story.

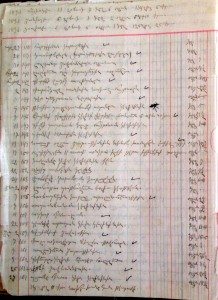

Siphora, an Armenian woman, worked as a midwife in Aintab from the late 1800’s to 1922. She kept a notebook detailing information on the babies she delivered beginning in 1890. By the time she left this city, she had helped deliver 4,274 children.

Four thousand. Two hundred. Seventy-four.

Siphora’s sister Nuritsa began practicing midwifery, also here in Aintab, in 1905. She, too, kept a detailed notebook.

Initially, many of the families they served were Armenians in the city. Siphora helped deliver a child for Rapael’s wife Zaruhie (January 1892, then March 1893), kuchuk (small) Nerses’s daughter Ovsanna of Nizib (October 1895), saddle-maker Avak’s child (March 1897), pilavji Nerses’s child (April 1897), deli (crazy) Gullu’s child (February 1898), carpenter Minas’s bride Khanum (June 1899), goldsmith Harutyun’s child (October 1899), and hundreds of other Aintab Armenians.

Then, after 1915, we encounter fewer and fewer Armenians in the notebook.

You know why.

Their clients were now primarily Muslims and Jews: gendarmes commander Kemal bey’s child (1916), Salonica refugee Mahmut effendi’s child (1916), Cabra’s wife Sara’s child (March 1918), and others.

Almost abruptly, in 1922, Siphora’s notebook has a simple entry: Antep’te işimiz bitti (We are done/our work is over in Aintab). Nuritsa writes in her notebook that on Nov. 29, they rushed to the train station with a number of orphans and escaped to Aleppo.

There, Siphora and Nuritsa continued their work, helping deliver children of survivors of the massacres.

A simple note at the end of Siphora’s notebook informs us that she passed away on May 28, 1940. Her sister continued working as a midwife for another decade and a half.

People of Aintab:

It is symbolic that the first time these notebooks are ever being publicly shown is in Aintab. Through these notebooks, today, the two sisters return to Aintab.

As I stand here today and look at you, I can’t help but think that there are many among you who are grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those Nuritsa and Siphora delivered a century ago.

Recall that number: 4,274 babies—Siphora’s alone.

It is likely that Nuritsa and Siphora were the first to hold your grandparents and great-grandparents.

Those two women, who served this town for decades, left with pain in their hearts and with three words on their tongue: Antep’te işimiz bitti.

You know why.

Like Nuritsa and Siphora, thousands upon thousands of Armenians left this town, never to be able to return again. But they took a piece of Aintab with them. How could they not? Their memories of their hometown. They lived with longing for their town until they died.

The few who had the opportunity to visit after they were forced to leave had a bittersweet experience rediscovering their ancestral home. George Haig was one of them. He left Aintab in December 1919 “for the United States to study agriculture and return to improve our properties: pistachio, olive, fig groves and vineyards and grain crops.” He wouldn’t return again.

You know why.

Only after 40 years, as a retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army, was George Haig able to visit Aintab. He wrote:

“… I was standing in front of our house. What a thrill, what a feeling, what ecstasy to be back home after so many years. Still, I did not yet realize fully that I was in front of someone else’s house. When I knocked at the door I was still under the impression that the door would be opened for me by one of my brothers or sisters. You can dream, can’t you? But when the door was opened by a 12-year-old girl, I woke up to the realization that I was now an outsider.”

Today, those who committed the massacres against Armenians in 1895, 1909, and then 1915 are long gone. Gone are also those who survived those massacres. Siphora, Nuritza, and Haig are all dead. But they did not take their memories with them. Through their accounts, their stories, and their notebooks, they passed their memories on to generations of Armenians growing up far from Aintab.

The grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Siphora and Nuritza are alive. They gave me the notebooks, which I am currently using in my research.

And the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the people of Aintab whom Siphora and Nuritza delivered are also alive.

Some may be sitting right here in this hall. Look around. They may be right here.

A hundred years after the Armenian Genocide, it is time for their memories to also be your memories.

It is time for you to tell the grandchildren of George Haig, Siphora, and Nuritsa that you are committed to truth and justice.

And that the time has come for us to change those three words ringing in our ears today, and say, instead: Antep’te işimiz başlıyor! Our work in Aintab is beginning anew.

The post Mouradian Speaks at First Genocide Commemoration in Aintab (Full Text) appeared first on Armenian Weekly.