On Jan. 18, the Toronto-Armenian community gathered to commemorate the 8th anniversary of the assassination of editor and journalist Hrant Dink, who was murdered in Istanbul on Jan. 19, 2007, in front of the “Agos” newspaper offices.

More than 700 people filled the Armenian Community Center to hear keynote speaker Fethiye Cetin, one of the most prominent lawyers in Turkey. Cetin was Hrant Dink’s lawyer while he was alive, and continued to serve as his family’s lawyer after his assassination, relentlessly pursuing and investigating the perpetrators of the still-unsolved murder.

I was the master of ceremonies of the event. The commemoration started with a candlelight vigil and a moment of silence remembering Hrant Dink, as well as the latest victims of intolerance toward free press, the murdered journalists of the Charlie Hebdo magazine in Paris.

Clik here to view.

Hrant Dink

I explained how Hrant Dink became a target of Turkish ultranationalists within the “deep state” that planned his murder, and how officials in the intelligence bureaucracy and state police didn’t move a finger to prevent his murder, even though there was overwhelming evidence related to its preparation and implementation. After a beautiful rendition of Gomidas’s “Andouni” and of “Anin Desnem ou Mernem” (words by Hovhannes Shiraz, music by Majag Toshikyan) by young soprano Lynn Anoush Isnar, accompanied by pianist Lena Beylerian, I introduced Fethiye Cetin.

Cetin was born in Maden, Elazig province, and studied law at Ankara University. She is recognized as being the foremost human rights lawyer in Turkey, specializing in minority rights cases. She defended Hrant Dink against charges brought by the state for “insulting Turkishness,” only because he dared to speak about the Armenian Genocide. In 2004, Cetin wrote a book, titled My Grandmother, revealing her Armenian roots. In it, she explained how her Armenian grandmother was captured as a nine-year-old orphan by a Turkish soldier during the death march of 1915. Although her grandmother was Islamicized—and her name changed from Heranoush to Seher—she kept her Armenian roots secret until she was 70 years old, and opened up to her granddaughter, Fethiye Cetin, asking her to find her long-lost brother. After years of searching, Fethiye did find her Armenian relatives in New Jersey, but only after her grandmother had passed away.

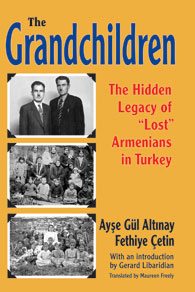

Clik here to view.

Cover of ‘The Grandchildren’

My Grandmother has been translated into more than a dozen languages. It immediately became a best-seller in Turkey, and opened the floodgates to hundreds of similar stories about hidden, Islamicized Armenians. As a result, Fethiye Cetin, in collaboration with Ayse Gul Altinay, edited another book, called The Grandchildren, a compilation of dozens of stories of hidden Armenians. She also initiated a restoration project for destroyed Armenian fountains in her hometown village of Habap in 2009; several Armenian, Turkish, and Kurdish youth from Turkey, the United States, and France came to Habap to collaborate with local villagers and reconstruct the historic fountains that supplied water to the village.

After Hrant Dink’s assassination, Fethiye Cetin represented his family in the murder trials and investigations, which are still unresolved and continue to this day. In 2013, she presented the failure of the judicial system in finding and sentencing the real perpetrators of the Dink murder, as well as the gross negligence and cover-up of state officials, in a book titled, I Am Ashamed: The Trials of the Hrant Dink Murder Case.

In a moving speech at the Jan. 18 event, Cetin explained the struggle between individuals’ memory and conscience versus state pressure to make people forget past crimes. Below are excerpts from the speech.

***

“My grandmother was about 70 years old when she told me her story, as seen by her as a 9-year-old girl, about the 1915 disaster, the death march, followed by silence, pain, and loneliness. Nearly 60 years had passed after the terror that she experienced, but my grandmother still remembered very clearly her village, her house, all the names of her relatives, including her grandmother, her grandfather, her cousins, even the name of the village official. Despite all the external attempts to make her forget, she remembered everything that she and her family had lived through. It was as if she had kept repeating the story to herself for 60 years, in order not to forget.…

Clik here to view.

Fethiye Cetin (Photo: Hetq.am)

“The official state version of history in Turkey is also subject to a similar policy of permanent amnesia regarding the 1915 events. A typical example is a statement given by Sevket Sureyya Aydemir, the author of Mustafa Kemal’s biography: ‘I believe the fighting and settling of accounts between Turks and Armenians is a page of human history best to be forgotten. Which side was responsible? Who was guilty? I think it is better not to find out answers to these questions and forget these events forever.’…

“But unfortunately, despite all attempts, laws, and pressures to make people forget these events forever, this policy cannot be implemented.…

“On the other hand, the state which forces individuals to forget the past keeps all the information, records, documents about the past under its control, in locked safes and rooms, in places beyond the reach of the public, in order to bring them out and use them as discriminatory policies against the minorities, the ‘sword leftovers,’ the ones defined as ‘others.’ In other words, in one hand the state uses every means to make people forget the past, but on the other hand the state never forgets the past and keeps reminding the people about the differences in the minorities. As a result, the forced amnesia policy becomes converted to a policy of continuous remembering.…

“With the emergence in recent years of many stories about the past, with biographies, books, films, documentaries, panels, and conferences, one can conclude that the monopoly of the state in controlling the past has come to an end.…

“Local memories have started a revival because the great crime was witnessed by all local people. Despite the attempts to wipe out traces of the past, it is impossible for the local memories to be forgotten.…

“Remembering and facing the past is now a must for the Turkish people.…

“Truth and justice are deadly fears of the perpetrator. The perpetrator attempts to hide the truth with all its might, mechanisms, and institutions. This is why memory is the enemy of the government.…

“In my country the most important name of this resisting force is Hrant Dink. Because Hrant Dink, with his stand, kept on reminding them of their past full of crimes, the past which they desperately tried to make people forget. Because Hrant Dink not only kept reminding them of the truth about the past, but everyone that he touched with his words—his readers, his listeners, his followers, people in the street—everyone believed him. They murdered Hrant Dink, because he stood right where the state had drawn the red lines, the taboos that it feared. Hrant Dink became the only visible target for the historical hatred against Armenians, and he stood in the crosshairs of both opposition and government forces.…

“The hatred for Armenians also became quite apparent in all the trials and investigations following the murder, as the perpetrator of the crime—the state—ensured that all the state officials would be exempt from any investigation. During these eight years since the murder, the competing forces in the government still use the murder as war material against each other.…

“I am one of the closest witnesses of Hrant Dink’s murder. I was with him in the court cases throughout the long preparation stage of the murder. My evidence is based on my eyewitness account. I presented and continue presenting to the judiciary and prosecution all I know, I see, I think about this murder. But unfortunately, all my efforts so far have ended up in countless binders or in notes attached to desk calendars. They were not included in formal prosecution inquiries, evidence that I pointed out was not investigated, suspects that I pointed out were not questioned.…

“The history of this country is full of cases where criminals are not tried, even if tried are not punished, where the perpetrators do everything possible to make the society forget the crime. Our history has countless political assassinations and unsolved murders.…

“I acted as Hrant Dink’s lawyer before his murder, and I am his family’s lawyer after the murder. Obviously I do not possess the force and resources of the prosecutor to uncover the real planners and perpetrators of this murder. I don’t have intelligence organizations at my control either, which could provide me with clues and information. I base my case only on what I witness, and what I see in the trial documents.

“Yes, our history is full of shameful events, unaccounted crimes, unsolved murders. We inherited this shame from the past, but we are responsible not to pass it on to future generations. I want to pledge, with you as witness, that I will try to bring to account all the shame and present a clean future to the next generations. My promise is a promise to Hrant, that I will continue to seek truth and justice, to the utmost of my abilities and until the end of my life.”

***

The Toronto commemoration was more proof that Hrant Dink’s legacy lives on and gains more momentum every year, both within Turkey and in all four corners of the world, with demands of truth and justice to prevail for 1.5 million Armenians plus one—for Hrant Dink himself.

The post Fethiye Cetin Speaks at 8th Hrant Dink Commemoration in Toronto appeared first on Armenian Weekly.