The following is the text of the speech given by Eric Nazarian in Ankara, Turkey, on Jan. 17, 2015, for the conference, ‘1915, Hrant and Justice.’ Henry Theriault, chair of the Philosophy Department at Worcester State College, also participated in the conference.

Thank you for being here today and for inviting me. When I was a kid I loved the Aladdin fairy tale. What child doesn’t want a genie in a bottle to grant three wishes? I remember my conversations with the imaginary genie walking home from school. I had a wish list that I would write down in my secret notebook. My wishes would vary from “I wish I could grow wings and fly” to, as I got slightly older, kiss Sophia Loren and sing like Charles Aznavour. Since 2007, my wish to the genie has remained the same around this time of year: I wish all of us today were celebrating Hrant’s Nobel Peace Prize with him and not commemorating the 8th year of his assassination.

Clik here to view.

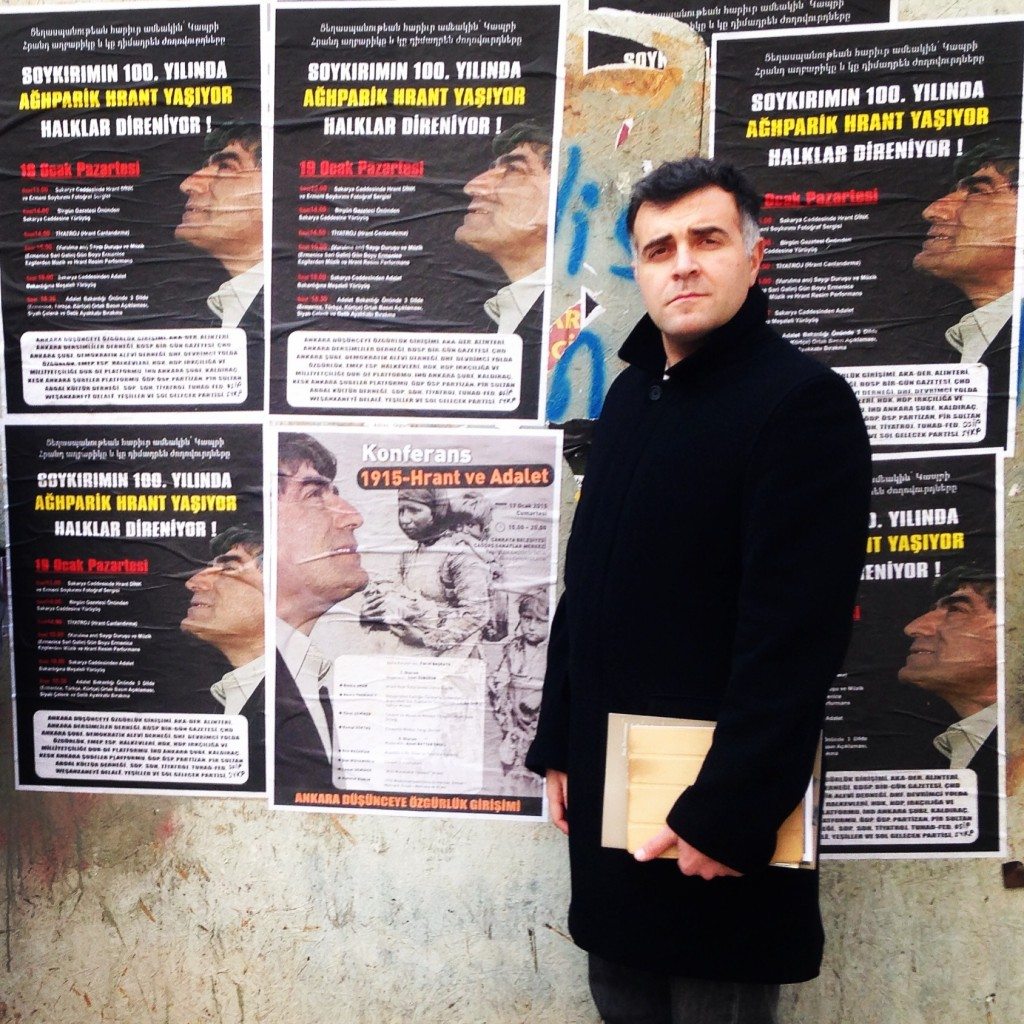

Eric Nazarian stands in front of posters for the conference, ‘1915, Hrant and Justice,’ in Ankara.

A lot has changed since those childhood days under the spell of Aladdin, Tom Sawyer, and Hovhannes Toumanian. Fairy tales, classic Hollywood movies, poems, and paintings all came to life on the dinner table of my parents’ and grandparents’ home in Los Angeles. My parents were born in Tehran, I was born in Armenia, my brother was born in Hollywood. As we say in Armenian: Vorteghits vortegh—from where to where—did we land? That is the eternal story of the Armenians.

Following in my father’s footsteps, I fell in love with the movies and books of his youth and grew up to become a filmmaker and writer. Black-and-white images were everywhere in our home. Marlon Brando, Stanley Kubrick, Simone Signoret, Albert Camus. These legends became windows into the world away from our working-class apartment, yet at the same time, they seemed so close and relative. They were inspiring, beautiful, and “harazat,” which means familial.

One of my earliest memories is of a wall in my family home with Charlie Chaplin next to a painting of Mount Ararat and Little Ararat. Laughter and majesty were side by side. The other image I remember wasn’t a painting or a film; it was one word in a poem by the magnificent Yeghishe Charents that my relatives would recite. The word was “arevaham.” Literally translated, it means “taste of the sun,” but it’s honestly lost in translation. I will never forget that word because it evoked the taste of sun-dried apricots. That’s what Armenia was to me—a sun-drenched ancient paradise where we came from. Charents taught me that poems, like images, could also make us see and feel things just like in the movies and music. As a child, this word and the images of my father’s favorite artists, including Martiros Saryan, Hakop Hakopian, Gabriel Garcia-Marquez, Federico Fellini, and Hovannes Aivazovsky, illuminated our daily lives. Before homework, after dinner, and during coffee and cigarettes, stories of these mythical artists, pictures, and movies on VHS continued to enrich our little apartment in Glendale. Art was the world and music was a universal tie that bound all cultures. These were the lessons I was taught as a child. To love culture, art, knowledge, creativity and to go beyond borders as a global citizen.

Then I learned of the Armenian troubadour and ashugh Sayat Nova, who composed and sang in all the languages of the Caucasus. Kani Vor Janim, Yar Ki Ghurbanim…

The voice, timbre, lament, and deep soul of those songs always evoked goose bumps and a teenage melancholia in my heart that I could not name. There was a warmth in that sadness wrapped inside Sayat Nova and Komitas’s blanket of music, and the images of the magnificent image makers that my father taught me about, among them Henri Cartier Bresson, Ara Guler, and the great photojournalists of the world.

Clik here to view.

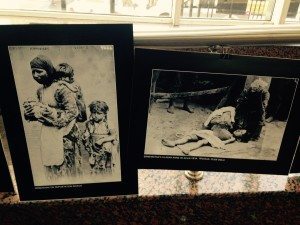

Black and white photographs from the Armenian Genocide lined the hallways leading to the conference in Ankara. (Photo by Eric Nazarian)

The honeymoon period during my “Arevaham” childhood in America inevitably came to an end in my teenage years when I discovered a different kind of image that was far from the well-composed glamour shots of Elizabeth Taylor, the vibrant oil on canvases of Martiros Saryan, and the sweet Parisian fragments of Cartier-Bresson. The image of my teenage years was a faded and scratched black-and-white photograph of eight beheaded Armenians piled on top of one another. This was when I learned of the Armenian Genocide and what had happened on April 24, 1915. This image opened a Pandora’s Box in my consciousness. Never again would I be able to look at images in the same way.

The photographer of this image was not Ara Guler or Yousuf Karsh or Cartier-Bresson. It was an anonymous person who clicked the shutter and, without realizing it, immortalized one fragment of unimaginable horror that has traveled 100 years, and will travel well into the future long after we are gone.

And with the sighting of this image, a psychological and personal journey began that lasted more than 20 years until this very day of a painful and endless education about the immensity of the Armenian Genocide and its immediate and long-term aftereffects globally. I learned of the name Armin T. Wegner and the images he secretly photographed of the deportations in the provinces he witnessed. Each image told a different fragment of a much bigger story about the people in them, and we have no way of knowing who they were or what eventually happened to them.

From Armin Wegner and the anonymous photographers that remain unknown until today, we have visual documentations of what happened on these lands 100 years ago. The deeper I went into photographic research, the mountain of stories got bigger and I found myself in a labyrinth of countless narratives. Survivors upon survivors. Orphans upon orphans. Horror upon horror. Similar narratives told by people on opposite sides of the earth who had managed to escape the inferno of genocide. I discovered them in books, in the letters and dispatches of American and European missionaries, in the wrinkled eyes of survivors and descendants that spoke volumes with their silence in documentaries. From Adana to Beirut to Los Angeles…vorteghits vortegh.

Clik here to view.

Conference goers walk by photographs depicting the horrors of the Armenian Genocide. (Photo by Eric Nazarian)

Well into my teenage and university years, my consciousness was very clearly split in half like a karpuz: On the one hand there were the celluloid heroes of my childhood and the glamour of Hollywood’s dream factory where everybody was happy and sexy. On the other hand, the darkness lingered over the ancient paradises of Historic Armenia where one and a half million of my people were annihilated in the hills, valleys, and deserts of the Ottoman Empire.

When the subject of Armenians came up in school, my teachers would tell me nonchalantly, “When I was a child if I didn’t finish my food, my grandmother always reminded me of the Starving Armenians.” Those two words, every time I heard them, erupted a burning feeling of humiliation I tried to keep buried inside. But I couldn’t.

In school, my American teachers didn’t know about Sayat Nova or Komitas or the word “arevaham.” Everything they knew about Armenians was relegated to a pop culture phrase that was seeded in America after World War 1 and well into the 20th century, continuing to this very day. When the subject of Armenians came up in school, my teachers would tell me nonchalantly, “When I was a child if I didn’t finish my food, my grandmother always reminded me of the Starving Armenians.” Those two words, every time I heard them, erupted a burning feeling of humiliation I tried to keep buried inside. But I couldn’t. One time I remember I ran out of class crying. At home, I would stare at the dinner table stuffed with Dadeeg’s delicious dolma and saffron rice and ponder the mountains of bones in the Der Zor desert. Why did the Turks do this to women and children? Who took the photo of the eight Armenian heads? The buried apparitions and visions eventually instilled a need to tell the story of my people and hopefully find catharsis through cinema.

And here we are in 2015, 100 years after the start of the genocide. Back then the Armenians were atop Musa Dagh fighting for their lives. And just a few months ago, the Yezidis were forced up Mount Sinjar fighting to survive. A lot has changed and a lot has stayed the same, unfortunately. In this quagmire that the Middle East has become in the past few years, lately I wonder a lot: What is my role as a storyteller? Why make images of suffering? Do stories and images even matter when tens of thousands of people are being uprooted, exiled, and deported just like the Armenians in 1915? What is the significance of images and stories during this very critical year that marks the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide? What images will come tomorrow that can hopefully heal and help us to face our pain and anger of being forgotten?

As an Armenian, we tell our stories and make images not to be forgotten. We build monuments worldwide to commemorate and immortalize through stone and mortar the martyrs for the nameless travelers of tomorrow’s generation. We film stories, put ink to paper, and digitize faded black-and-white photographs by Armin Wegner hoping that the preservation and knowledge of the genocide’s past atrocities can lead to the prevention of future ones. We also seek justice for a monumental crime against humanity that Hitler used as an example on the eve of invading Poland in 1939. This very same crime against humanity was an impetus for a young lawyer named Raphael Lemkin to coin the word “genocide.”

Empires and kingdoms draw lines on the earth that continue to shift based on impermanent power structures, but the truth remains rooted and untouchable, regardless of time, ravage, and injustice. The themes of justice and healing and the threat of erasure have evolved into themes central to the Armenian psyche worldwide since the genocide. It informs our art, music, images, poems, and daily yearnings to find wholesomeness within the broken root of our homeland that has been restricted to us. One century or several, the stones in Akhtamar, Palu, Soradir, Sassoon, Bitlis, Kars, Moush, and Diyarbakir continue to tell our stories and remain standing as a testament that the past will never fade and the truth is to be found within that past.

Today, I landed in Ankara by way of Los Angeles and Bolis. I first came to Turkey in 2010 when I was invited to make a film about the Armenians of Istanbul for an omnibus called Unutma Beni Istanbul (Do Not Forget Me Istanbul). The title of my film is “Bolis,” the Armenian word for Istanbul derived from the Greek name “Konstantinopolis.” Again, as a storyteller I was drawn to themes of memory and not being forgotten. I wanted to make the film a love letter to Old Bolis, Eski Bolis, as seen through the eyes of an ambivalent Diaspora Armenian oud master returning to Kadikoy with only a photo of his grandfather’s oud shop on a street called Tellalzade.

Just before docking in Istanbul, I experienced a silent panic attack in the plane above the skies of the Bosphorus. My mind suddenly became raided by images of Komitas, Daniel Varoujan, Siamanto, and Krikor Zohrab being arrested in the dark April night and driven to the interior on trains. I thought of Zabel Yesayan fleeing in the night. I thought of my American teachers uttering the words “Starving Armenians.” I thought of the ocean of bones in Der Zor…What the hell was I doing returning to the epicenter of the genocide?

Just before docking in Istanbul, I experienced a silent panic attack in the plane above the skies of the Bosphorus. My mind suddenly became raided by images of Komitas, Daniel Varoujan, Siamanto, and Krikor Zohrab being arrested in the dark April night and driven to the interior on trains. I thought of Zabel Yesayan fleeing in the night. I thought of my American teachers uttering the words “Starving Armenians.” I thought of the ocean of bones in Der Zor…What the hell was I doing returning to the epicenter of the genocide?

Clik here to view.

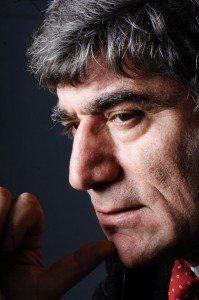

Hrant Dink

The answer, tragically, was simple and current. Hrant Dink. What he stood for and what he fell for became the third awakening in my life. I needed to see the city he loved so much. I needed to breathe in the air of Istanbul, despite my silent panic upon seeing the city for the first time from a bird’s eye view. We landed but the dread hung over me as I roamed the streets of Istanbul with a group of filmmakers who fast became friends—and helped me realize my cinematic mission to make a film about the long-term effects of the genocide on a Diaspora Armenian with an oud and a mission to find his grandfather’s music store in Kadikoy. He searches to find something that no longer exists and ultimately finds something he did not expect: a brief moment of friendship and empathy. Perhaps my film reflected my own journey. I came here to find the echoes of old Bolis. But I was really looking for empathy. I was looking for Hrant.

In the film, Armenak, the lead character, is asked by another character if he likes Istanbul. He replies ambivalently that “the demons of the past will never let me forget what happened here in 1915.” For us Armenians returning to this ancient city, we see the majesty of the surface geography, but everywhere we turn we are haunted first by buried apparitions of faces, places, and histories that have been erased from the collective consciousness and the history books.

This is why it is important, now more than ever, in the wake of Hrant, to continue to tell the stories and live to see the stories told. Through storytelling, we can rectify the lies that have polluted the truth of the ravaged and buried histories of this region’s minorities: Kurds, Greeks, Jews, Assyrians, and Armenians.

And in telling our stories, we nurture the need and hopefully fulfill the first steps of attaining justice. Telling stories is an act of civic rebellion as much as a protest.

Refusing to be silenced, refusing to be dehumanized, refusing to be forgotten, singing louder and clearer and more resolute all the truth that must be told is where I find the courage in men and women in this region and worldwide still suffering from the plagues of genocide, injustice, displacement, exile, and racism.

The broken record player of history has been repeating itself in strange and ugly ways this past year. I hope that through civil society groups, open hearts, and a refusal to dilute or distort the suffering of indigenous minorities, there may be a deeper justice and a new awakening found. With citizens waking up to the nightmare that was our history on these lands 100 years ago, may they combat intolerance and the denial of the Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian Genocides with empathy, open hearts and knowledge that dispels the lies.

If I could convince myself today that the genie of my childhood would come alive again on my shoulder and grant another wish for tomorrow, I would wish for every child in the world to know the story of this beautiful human being named Hrant Dink, and for his message of peace and sincerity to be sowed in our hearts to guide us toward a true path of reconciliation through truth, justice, and empathy. The memories of the Tigris and the Euphrates are very long and the pen will always be mightier than the sword.

The post A Wish for Aladdin and the Future of Atonement appeared first on Armenian Weekly.