Special for the Armenian Weekly

Travellers visiting the bustling city-state of Singapore may not be aware of the great impact made by the Armenians who form one of its smallest minorities. Between 1820 and 2000, fewer than 700 Armenians ever lived in Singapore. Although most were transient, with a mere 12 families residing for three generations, they have left a legacy incommensurate with their numbers. Along with the Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator, the oldest existing church in Singapore and its parsonage, there are other reminders of the Armenian presence. These include Raffles Hotel, the Straits Times newspaper, and Singapore’s national flower, Vanda Miss Joaquim.

Clik here to view.

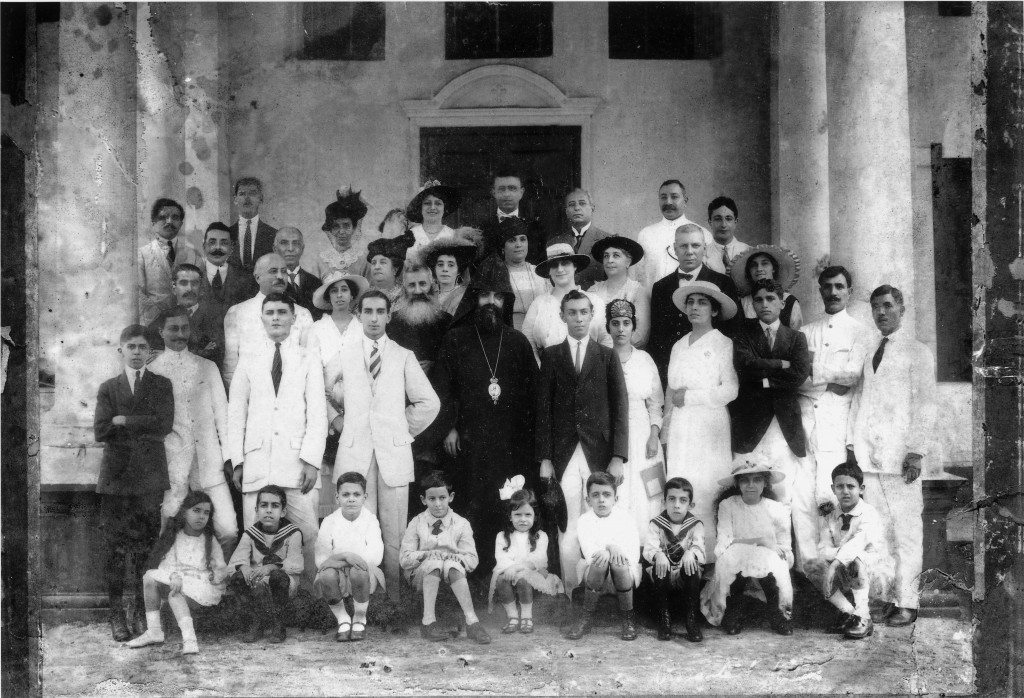

Members of the Armenian community of Singapore in 1917

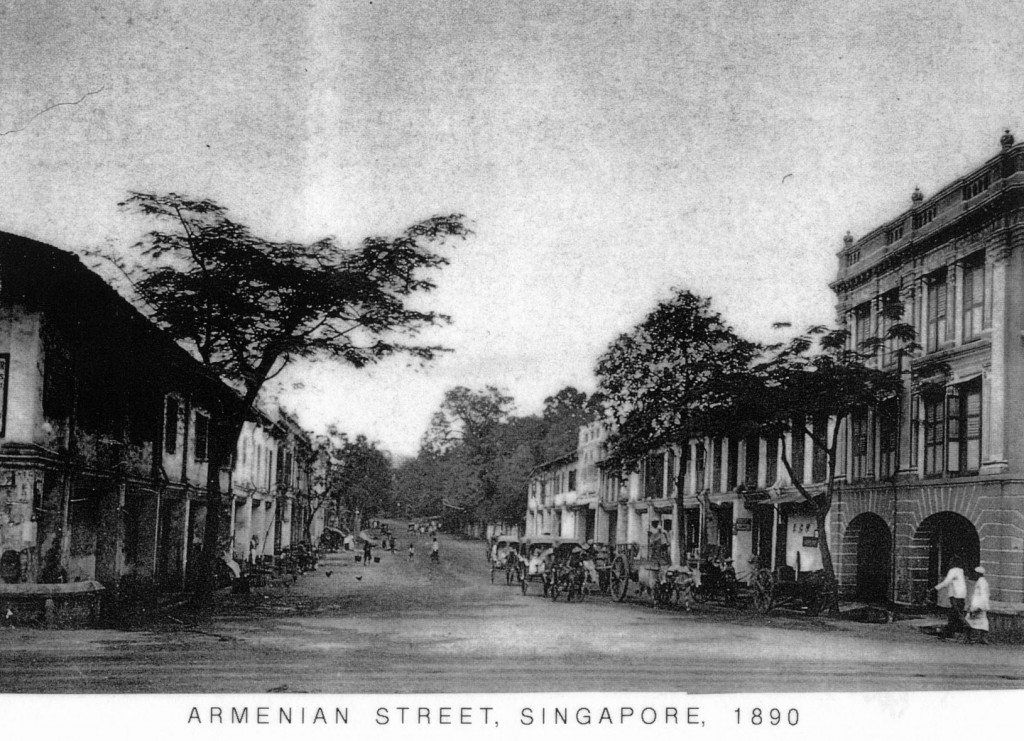

As in most cities where Armenians settled, there is an Armenian Street. In Singapore, this short street gained its name because it bordered the back of the church property. Three other streets attest to the Armenian presence: Sarkies Road, named after property owner Regina Sarkies; Galistan Avenue, which recognizes the work of Emile Galistan of the Singapore Improvement Trust; and St. Martin’s Drive, which commemorates the philanthropic Martin family who once owned a mansion and substantial property along Orchard Road. Stamford House, built by the firm of Stephens Paul in 1904, still stands offering insights into Edwardian architecture.

Clik here to view.

Armenians in Singapore in 1960

So, when and why did Armenians arrive in Singapore and what happened to them?

They were descendants of Armenians from Persia, in particular those deported from Julfa to Isfahan by Shah Abbas in the early 1600’s. In later years some of those Armenians migrated to India, the Dutch East Indies, Burma, Malacca, Penang, and lastly to Singapore, thus forming an extensive trading diaspora. To better assimilate, most Persian Armenians Anglicized their names; thus some surnames are not recognizable as Armenian. For example, Mardirian became Martin, Stepanian became Stephens, and Yedgarian became Edgar.

Clik here to view.

The tombstone of Sarkies A. Sarkies who passed away in 1849

In 1820, one year after the British opened a trading post in Singapore, the first Armenians, the apparently unrelated Aristarkies Sarkies and Sarkies A. Sarkies, arrived from Malacca. They were soon joined by Carapiet Phannous, Mackertich Moses, the Seth brothers, and the Zechariah brothers. All were traders or commercial agents. By 1824, there were 16 Armenians out of a population surpassing 10,000. More arrivals trickled in hoping to make their fortunes in the new duty-free port.

Before long, the Armenians wanted their own priest rather than relying on visits from the priest in Penang. In 1825, Isiah Zechariah, on behalf of the community, wrote to the archbishop in New Julfa asking that a priest be sent to Singapore, and in 1827 Reverend Gregory Ter Johannes duly arrived. The next step was for the Armenians to have their own church. Having been granted land by the governor, the community, which was basically comprised of 10 families, raised most of the construction costs. In 1836, the Armenian Apostolic Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator was consecrated, and for the ensuing century met the needs of the growing community.

Between 1820 and 1983, Armenians in Singapore operated more than 85 commercial enterprises. Most set up as traders, specializing in importing textiles and exporting regional produce. Such firms included Andreas & Company, Edgar & Company, Demetrius & Company, Arathoon Brothers, and Chater & Company. The Calcutta-based Armenian shipping line Apcar Brothers was patronized by the Armenians, and was also the main carrier of the then-legal opium into Singapore from the 1860’s until the 1880’s.

Some firms petered out after a short time, whereas Sarkies and Moses, founded in 1840, lasted until 1913. Others developed into multinational import and export firms, including Edgar Brothers (1912-68), Stephens, Paul, and Company (1896-1941), and A. C. Galstaun (1957-83).

Clik here to view.

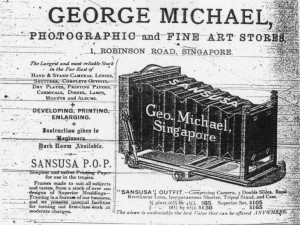

George Michael ran Singapore’s leading photographic studio until 1919

A few individuals owned law firms, restaurants, watch-making, and jewelry shops, auction houses, small factories, and photographic studios. The legal firm of Joaquim Brothers was well known throughout Malaya until its closure in 1902, while George Michael was running Singapore’s leading photographic studio when he left in 1919.

The hospitality industry attracted many Armenians, their ventures ranging from small boarding houses to the grandest of hotels: Raffles Hotel. This future icon was the initiative of Tigran and Martin Sarkies, who were already running two successful hotels in Penang: the Eastern Hotel and the Oriental. Propitiously, they named their hotel after Sir Stamford Raffles, Singapore’s founder, whose statue had recently been unveiled amidst much pomp and splendor.

Clik here to view.

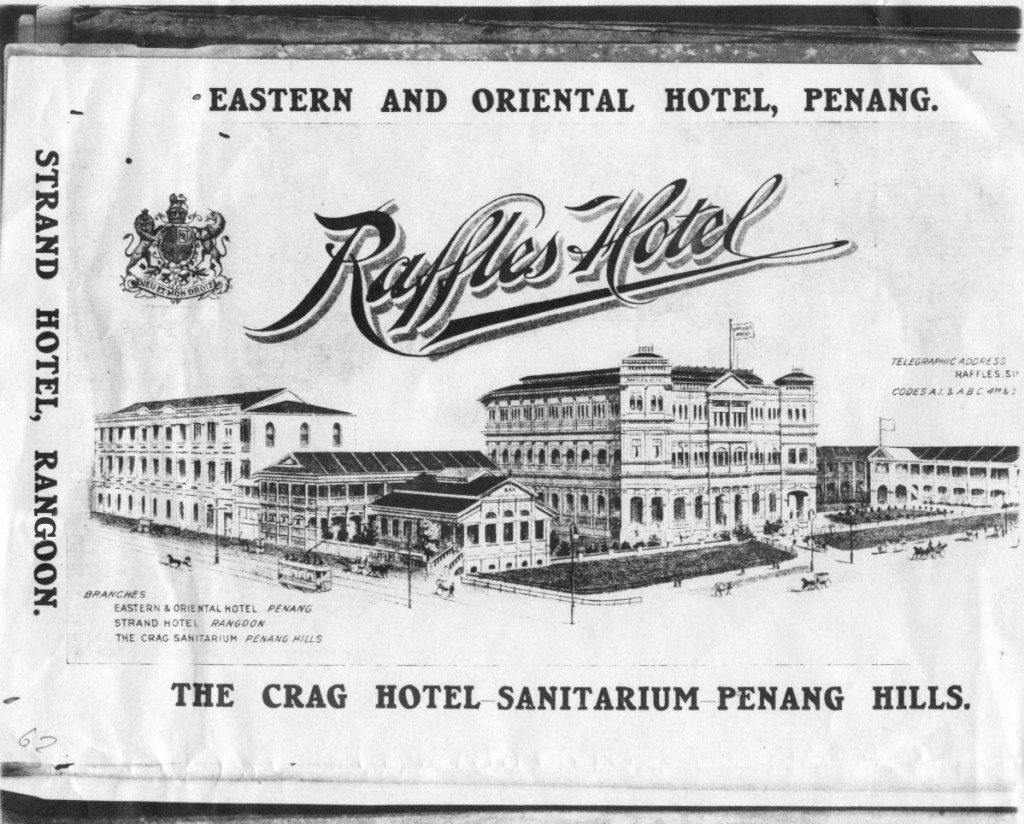

An advertisement for Raffles Hotel

Opened in December 1887 and managed by Tigran, Raffles Hotel quickly established a reputation for its dining innovations. Its fame escalated after its magnificent new Renaissance-style block was opened in 1899. The grandest balls and banquets were hosted at Raffles, and guests included royalty and celebrities such as Somerset Maugham and Noel Coward.

Managed by Tigran for nearly 20 years, then his younger brother Aviet for another 10, the hotel reached its halcyon days in the 1920’s under managing proprietor Martyrose Arathoon.

Clik here to view.

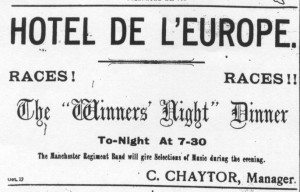

Advertisement for Hotel de l’Europe

For a short time at the turn of the 20th century, the three major hotels in Singapore were managed or owned by Armenians. Competing with Raffles was the Adelphi Hotel run by Johannes and Sarkies, while even the exclusive Europe Hotel was being managed by Joe Constantine. Before that, there had been a series of Armenian hoteliers operating smaller hotels, including Moses’ Pavilion and Bowling Alley, St. Valentine’s Bath Hotel, and Goodwood Hall and the Sea View Hotel, which was finally acquired by the Sarkies brothers. The Oranje Hotel, in today’s Stamford House, which was run in the 1950’s by Klara van Hien, was the last of the Armenian hotels.

Some of the pioneering merchants built or acquired magnificent houses, and played a significant role in the educational, economic, civic, and social life of the colony. They served on various committees including the first Chamber of Commerce, which met in 1837. In 1895, two out of the eight elected municipal commissioners were Armenian: a very high ratio for such a small community.

A notable individual was prominent lawyer Joaquim P. Joaquim (Hovakimian) who served as president of the Municipal Commission, a member of the Legislative Council, and was appointed deputy U.S. consul in 1893. Another prominent figure was George G. Seth, who rose to become solicitor-general of the Straits Settlements in the 1920’s and later served as acting attorney-general.

Clik here to view.

Agnes (Ashkhen) Joaquim

One Armenian who received posthumous fame was Agnes (Ashkhen) Joaquim. In the 1880’s she hybridized an orchid by crossing the Vanda teres with the Vanda Hookeriana, thus creating the flower named after her: the Vanda Miss Joaquim. Propagated by cuttings, this orchid proliferated not only in Singapore but in the other tropical countries where it had been introduced. It became especially popular in Hawaii, where it is better known as the Princess Aloha orchid. In Singapore, the orchid was selected as the nation’s national flower in 1981.

The Armenians were very loyal to Britain; Hoseb Arathoon, for example, donated an aeroplane to the British War Office in 1915, and young men volunteered for both World Wars. The community was also acutely aware of the suffering of their brethren in Turkey and raised large amounts of money for the victims of the massacres of the 1890’s and later the genocide.

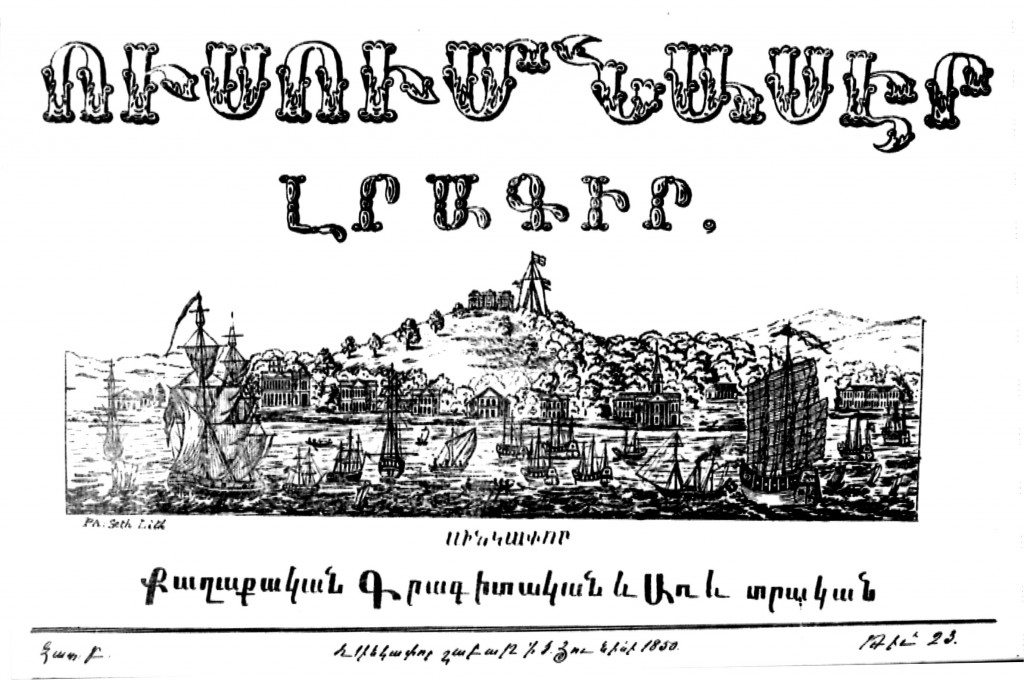

Although the community was too small to run its own school, an Armenian newspaper was printed for a short time. Gregory Galastaun published “Usumnaser” (“The Scholar”) from 1849 until 1853, with his friend Peter Seth creating an exquisite etching of Singapore for the masthead.

Clik here to view.

Gregory Galastaun published ‘Usumnaser’ (‘The Scholar’) from 1849 until 1853, with his friend Peter Seth creating an exquisite etching of Singapore for the masthead.

Clik here to view.

In 1845, Catchick Moses established the ‘Straits Times’ newspaper

In 1845, Catchick Moses had established the “Straits Times” newspaper, which today is the leading newspaper of Southeast Asia. Moses had acquired the printing press to help out his beleaguered compatriot, Martyrose Apcar, but soon sold the newspaper to the paper’s editor, Robert Woods.

‘Armenian numbers peaked at just over 100 in the 1920’s. A branch of the AGBU was up and running, Raffles Hotel was in full swing, and the trading firms were busy and all employed young Armenian men often from other Armenian communities. However, this was the calm before the storm. First came the Depression, which adversely affected the trading companies in particular; then in 1938, the last resident priest returned to New Julfa; and in 1942 Singapore fell to the Japanese. The Armenians suffered diverse fates: Some women and children escaped to Australia, while their menfolk enlisted. Civilians who were British subjects were interned, while those who were classified as Persians were not. Death struck both soldiers and civilians.

After the war, a new Singapore emerged: one in which Armenians faced limited prospects. The few Armenian firms included Edgar Brothers and Arathoon Sons, and A. C. Galstaun, which was the last of the Persian-Armenian firms. Gradually the families migrated mainly to Australia, the U.S., or Britain.

By the 1970’s the community had virtually disappeared; only a handful of the old families who still spoke Armenian remained. The very smallness of the community, which had helped it to integrate, also helped cause its demise: It was demographically unviable. Intermarriage and the consequent assimilation into a larger culture, death, and emigration had taken their toll. In 2007, Helen Metes, the last of Singapore’s Persian Armenians, died.

But not the Armenian community of Singapore. This has been revitalized by the recent migration of Armenian entrepreneurs from Armenia and Russia. Along with other expatriates they are creating a new, vibrant, and growing young community, building on the past to secure a sound future for Armenians in Singapore.

Clik here to view.

Armenian Street, Singapore, 1890

Clik here to view.

Armenian Street today

The post The Armenians of Singapore: An Historical Perspective appeared first on Armenian Weekly.