Special for the Armenian Weekly

“Before traveling to Europe, [Armenian writer Yeghishe] Charents visited this city with his good friend, Avetik Isahakian. It’s unclear as to how long he stayed; perhaps 10 or 15 days. I’m not completely sure. It is said, however, that he stayed in this building, which used to be a hotel. This is a historic building belonging to the Karagozian Foundation. He also mentions the Pera Palace in his poem entitled ‘Istanbul,’ so he might have stayed there too. The details don’t really matter. What is certain is that he roamed around these streets. That we know. In that same poem, he calls the city an ‘international whore,’ and he was right. It sure as hell is an interesting place to live.”

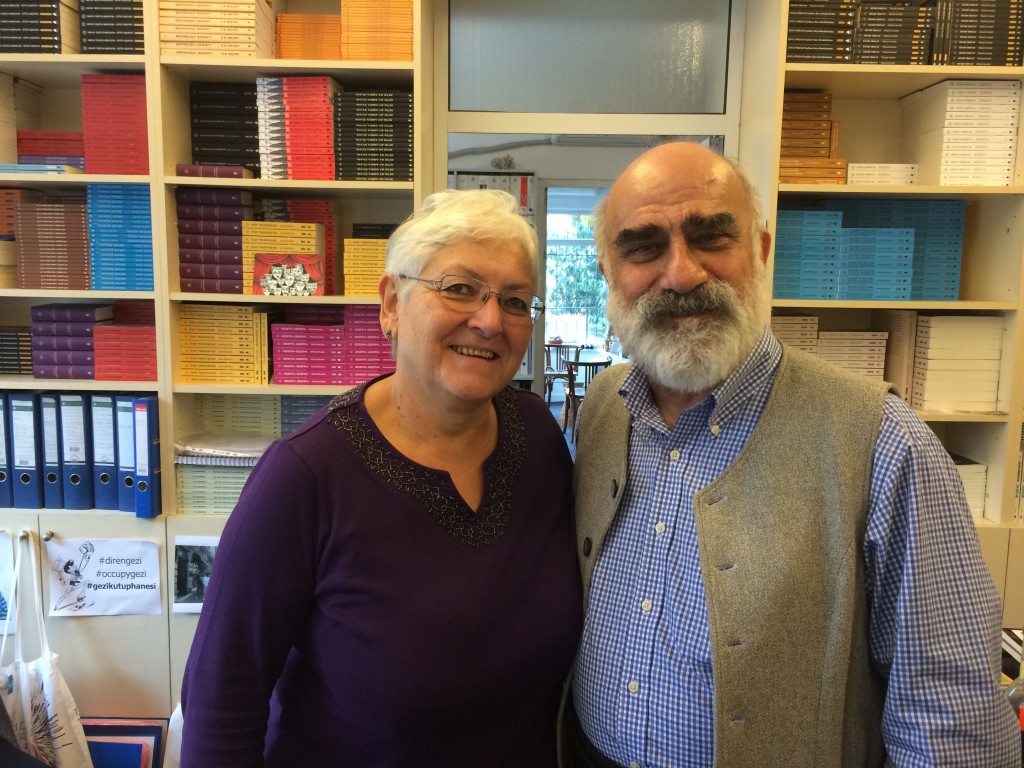

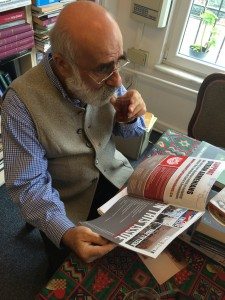

Meet Tomo of Istanbul: a 65-year-old man with a glorious beard and about a thousand stories. He sits in his office in the district of Beyoglu sipping on his dark tea and ready to share. Born Yetvart Tovmasyan in 1949, he is a staple in the Armenian community of Istanbul.

He doesn’t like to be called by his real name; only his wife, Payline, who he boasts has been with him for 45 years now, has that privilege. He prefers to be called Tomo.

“There were three Yetvarts in my class at the Tbrevank in Iskudar, so we had to differentiate. First they called me Tovmas, then, in pure Armenian fashion, it was shortened. Sarkis becomes Sako, Dikran becomes Diko, and I guess Tovmas becomes Tomo.”

Tomo studied classic philology at the University of Istanbul, where he focused on Classical Greek and Latin. During that time, he also studied and mastered Classical Armenian (Krapar) at the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul. After graduating, he got married, and along with his wife voluntarily worked at the Armenian daily newspaper Marmara, where they published the children’s page every Friday. It was during those years that Tomo and a group of intellectual friends, which included renowned Istanbul-Armenian author Mgrdich Margossian, began publishing books. They would translate Armenian books into Turkish and Turkish books into Armenian, and print them with the little money they could put together. Their first publication, Margossian’s Mer Ayt Goghmeruh, quickly became a hit among the Armenian community. Years later they decided to open a publishing house for real.

“Hrant Dink had a bookstore those days. I suggested to him that he should start a publishing house with Margossian. Initially, I wasn’t interested in being a part of it. They had a few meetings about it and decided they wouldn’t go ahead with the project if I wasn’t going to take part. Apparently giving the idea wasn’t enough.”

And thus, in 1993, Aras Publishing officially opened its doors. Its three founders, Margossian, Dink, and Tomo, rented a small space on the second floor of the same building the publisher occupies today and began their little operation. Dink would leave the team three years later to pursue his dream of publishing a Turkish-language weekly, which focused on Armenian and other minority issues. Tomo admits that he wasn’t happy to see Hrant go, but is now glad he did.

“There was a need for both Aras and Agos in Turkey, and I think we both successfully filled that void. We’re still sister operations today. We both have one similar purpose.”

The purpose, according to Tomo, is simple: to help bring together Turks and Armenians to solve the 100-year-old elephant in the room.

“We know about the genocide…We were all affected, one way or another. But the public in Turkey is unaware. It is our duty to teach the public about our history, our literature, and our culture. I’m often asked, ‘Where have you Armenians come from?’ and I tell them that we’ve been on these lands for thousands of years. I don’t blame them. They don’t know about us. They have never been taught the truth.”

According to Tomo, the best way to educate is through the arts. “If we can teach the general public about our people through our literature, our songs, and our dances, then the peace process will commence much easier. If the Turkish people learn the truth about the past, they will surely demand their government to do the right thing and acknowledge their history. These people have a voice and a vote in this country. It is our duty to educate them properly; they will do the rest.”

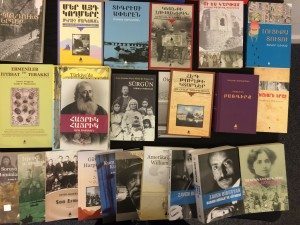

And the Aras Publishing House is doing just that. Over the past 21 years, they have published 150 books: 40 in Armenian and 110 in Turkish. Some have even been translated into other languages, including Kurdish. Every one of the books published has either an Armenian author or an Armenian theme.

Unfortunately, the business is not very profitable, but Tomo doesn’t seem to care. He believes that the work he does serves a higher purpose.

“Our problems won’t be solved without dialogue. Turkey is changing. Just 10 or so years ago, there was a conference organized here by Armenians and Turks who wanted to start talking about coming to a peace. People threw eggs and tomatoes at the presenters, posters were torn down, and the conference was quickly canceled. Today, there are conferences being organized not only in Istanbul, but even at Ankara University, about opening the borders and discussing our history. The books we publish are a small part of this dialogue that is beginning to take shape here.”

Istanbul is changing and so is its Armenian community. Tomo says there are about 3,000 Armenian students attending the 20 or so Armenian schools left in the city—a student body that has been steadily dwindling over the years. People don’t attend church as much as they used to, and the pews are at full-capacity only at Easter, Christmas, and a few other religious holidays throughout the year. Armenian isn’t spoken much among the community, which was once the hub of Western Armenian literature. The community is now made up of people from smaller towns and villages where Armenian schools didn’t exist, Tomo explains.

“Most of our community learns Armenian when their kids go to Armenian school. They learn the language with their children. Armenian is not spoken half as much as it once was in this city. We print 500 copies of each Armenian book we publish and can barely sell them all in 4 or 5 years. We print twice as many copies in Turkish.”

But Tomo is not worried about his beloved city and the Armenian community.

“I often read articles written 50 or even 100 years ago. The problems were much the same then as they are today. People were always complaining about the community dying and disappearing. The fact remains that we’ve been living here for thousands of years and enjoying all this place has to offer. I consider myself very lucky to have been born here and in this great civilization of Armenians. We will always complain and criticize, but life goes on as usual. We are still here and we will remain. This is our home.”