Special for the Armenian Weekly

When my son was born in 2007, I named him Armen simply because I could. When I was born in 1978, as Armenians in Baku, Azerbaijan, my parents were too scared to name me Anoush. That was the name they really wanted for me, the name of both my paternal great-grandmothers from Zangezur. But it was too Armenian for an Armenian minority in Azerbaijan. Instead, they settled for Anna—a safer version, one that would not project a spotlight on me from birth. But in 2007, in the United States of America, I could name my child anything I wanted. And I named him the most Armenian name I could find. It was a tribute to my ancestors.

Twenty-two years in the U.S. as Baku refugees were not easy, either financially or emotionally. We came here with $180 and 4 suitcases, and eventually built a successful life. But my pain, my longing for normalcy, and my memories were too much to handle head on. I worked hard to become a normal teenager, a normal young adult, a normal American, hoping to blend in and forget. But I never really fit in. Not with Americans and not with the local Diasporan Armenians. Mine was a refugee fate. Two decades were spent hiding from what happened to my people. Two decades were lived avoiding the news from my homeland Azerbaijan, my ancestral home Armenia, and the heartache in between—Nagorno-Karabagh, whose people demanded their rightful independence from Azerbaijan and triggered the retaliation against innocent Armenians in Azerbaijan and Karabagh. My job was to blend in and build a good life for my children, my parents told me.

But the years of throwing myself into everything but Armenia were ending. As I began to read through the pages of the book I wrote so many years ago, at age 14, I ended my self-exile. The words of that child seemed so untarnished, clear, and innocent. As I read my own words, I remembered them, but felt like a stranger to my own memories. I was struck that they were mine. We lived liked this? The feeling of outrage took over me: a child, me. A child went through ethnic cleansing and exile. My maternal instincts kicked in. This book needs to be printed, read, and understood. I have to go back and find the people that were left behind. The Armenian people of Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabagh, dead or alive, deserve to be known globally.

After a two-year tour of the U.S. with my book, Nowhere, a Story of Exile, a diary I kept as an Armenian child in Baku, I was ready to return. It was September 2014. The flights were booked. The bags were packed. There cannot be a better way to return to your ancestral home than with love and forgiveness, I thought to myself, surrounded by the proud but quiet humming of your ethnicity in every aspect of your life.

The fact, though, is not so simple. Is it ever simple for an Armenian? When we left Baku in 1989, we came to Yerevan with nothing. We were refugees. The country was in no condition to receive us after the earthquake, with the blockade and the impending war and independence from the Soviet Union. The people were also in no condition to receive us, including our own family members. Anger, fear, and darkness had taken over everyone. A handful of relatives helped us. Many didn’t. Some were ashamed to seat us for dinner with other guests. I received violent threats of beatings from Armenian teachers and heard obscenities yelled at me in public markets for being from Baku. As adults, my parents were happy to be safe from the ethnic violence. They found jobs, but there was nothing to buy with the money we saved. We couldn’t find food day to day, let alone a decent place to live. There was no future for us in Yerevan. The conditions we lived in were subhuman, and there was no other choice but to leave my grandparents’ homeland.

As a child, the resentment that drenched my little heart from this treatment in Yerevan stayed with me for years. And it’s not isolated. It stays with many Baku Armenians in Russia, Western Europe, and United States. It often overshadows other reasons why conditions were so bad—because we saw humans at their worst in Baku, and then were seen as traitors or un-Armenian by many in Yerevan. That is one of the reasons why some from the older generation became isolated from the larger diaspora communities. And they continue to view Armenia in the same light they viewed it in the early 1990’s. However, I’m beginning to notice that the younger generation is past that. Many view Armenia as their ancestral homeland. Baku is a distant detail in their family’s history. And I am somewhere in between the two.

As the airplane landed in Zvartnots, I was disappointed that my emotions didn’t overwhelm me. Armenia, especially Zangezur, after all, is the place where my roots go back thousands of years and the place I often dream about and relate to, more so than Baku where I was actually born. Even as I recognized the faces of the aged and changed relatives in the greeting area of the airport, I was teary-eyed but composed. As we drove through Yerevan close to midnight, nothing seemed like it was. So much was built; so much changed. Maybe Westernized, I thought, looking at the colorfully lit streets and storefronts. Perhaps I was tired, jetlagged, or emotionally barricaded, but aimlessly I kept searching deep for a connection.

After spending several days with my relatives for the first time in more than 22 years, one of the first of many official events I participated in was sponsored by the Armenian Ministry of Diaspora. Minister Hranush Hakobyan and the staff graciously welcomed me and my book in their offices close to the Republic Square in Yerevan. The presentation was well received, and the great emotion and love shown by the audience and fellow presenters after my speech was stunning. Many accepted my honesty and conceded the tragedy of the Baku Armenians both in Azerbaijan and in Armenia. I was welcomed as an Armenian, despite my inability to speak Armenian, or not being born there. I was surprised—and unarmed—immediately. This was all too new for me.

That evening, my father and I walked out of our hotel and strolled along the streets in the warm Yerevan night air. We walked to the Republic Square, through the crowded yet surprisingly relaxing streets, and I was completely taken aback by the scene that unfolded in front of me. Thousands upon thousands of people were on the square enjoying the musical fountains and lights. Children of all ages were dancing to the music with flowers and balloons. Lovers were holding hands by the fountains or strolling around in this bright darkness. Tourists and Yerevan residents alike were walking around enjoying the scene. The center of the independent Armenian Republic was blooming.

And that’s when it happened.

I bent down in uncontrollable sobs. My father was confused, trying to help me. I cried for a good few minutes. When I was able to speak, I said:

Look at these people, Papa, look at them. They are never going to be destroyed. When we lived here, there were no celebrations, no colorful Armenian flags, and the fountain pools were used by children to cool down in the heat in the middle of a blockade. We had no electricity, now look at these color fountains. We had no food, now look at these filled stores and markets. We had no coats and shoes, now look at all these wonderful clothes people are wearing. Everything was grey, now it’s so colorful. Their faces are smiling. Do you remember anyone smiling on the streets back then?

I tried to explain the pride I felt in the achievements of this little country in the most horrible circumstances that could befall a nation. Genocide, earthquake, war and blockade. My father hugged me. He understood; he didn’t need an explanation. My parents were the ones who suffered to provide us with food and shelter and clothing as refugees. As an adolescent I was just a helpless observer.

Since that moment at the heart of Yerevan, my experience in Armenia was an awe-inspiring rollercoaster of emotions and color. I visited relatives, historic sites, and the dungeon-like room where all four of us lived as refugees for more than two years. I spoke to students in Yerevan in both Armenian and American universities and noted the optimism and worldliness in their view of Armenia’s future. Many of them can’t understand the animosities I encountered in Yerevan, or the violence I encountered in Baku. That is progress. It all starts with the new generation of leaders, with their ideas and courage.

I met with non-governmental and governmental leaders alike and got inspired by their words, plans, and actions. They were thankful for the work I was doing to better relations between the diaspora and Armenia, and to gain recognition for the Nagorno Karabagh Republic. The journalists who interviewed me were interested in my story and the story of so many Armenians from Azerbaijan. Perhaps 25 years late, but our story is being told by my generation and slowly by the bigger, global Armenian community. Our parents are too pained to revisit our past, and all of us need to help them memorialize it. The fact that we are talking about it is progress, and I encourage my fellow Bakintsi to memorialize and publish their family stories in books and songs and paintings, as I know many of them are currently doing. I also encourage them to visit Armenia and experience it the way it is now. You will be surprised.

While in Yerevan I tried to gauge the mood of the country through random conversations with hotel staff, taxi drivers, and store clerks, along with new and old friends. The in-depth discussions with my Yerevan relatives also gave me a glimpse into the frustrations of the capital city, the stories of the outrageous spending habits and actions of oligarchs and the general feeling of frustration and inability to succeed. Many Baku-Armenian refugees still live in horrendous conditions despite two decades of pleading for governmental help. Their lack of adequate housing is still an ongoing issue, just like it was when we lived there 22 years ago. Many professionals work in blue collar jobs because their professional jobs don’t pay well enough to live. Many have left the country for work in neighboring countries such as Russia. Clearly many issues still exist.

With all that, nevertheless, there is also such pride in the progress. “Anna, don’t you feel like it’s a true European city?” I often heard from family members when discussing Yerevan. Yes, yes I do. And more. Aside from all the luxury cars, iPhones, brand name clothing, and abundance of food and everyday products we never even dreamed of in the 1990’s, it’s a European city of an ancient country where love saturates every stone and every stream, where history intertwines with the future, and children dance in the streets until nightfall. This is the land where life is simple and beautiful despite the country’s stagnating problems with Soviet-era corruption and bureaucracy. There is deep pride in every new building that’s built, every new road that’s paved, and every 100th tourist bus that rolls in daily. There is pride in the country’s growing IT field and the talent that graduates from its universities and colleges. There is personal pride in the successes of each family member, little at a time. And you can sense this pride in the changes the country has made throughout the land.

While visiting the rest of the country, especially the rural areas, the needs of the people appeared different. It was generally more positive: simple, hard working people were happy, purely because there was no more war and there was food to feed the children. One such experience was in Khndzoresk, the village where my paternal grandfather was born, the region where my paternal grandmother was from, and where my father spent summers as a child. The history of the region deserves a separate book, let alone a mention in an article. The old Khndzoresk village, a breathtaking marvel of Armenian history, is visited daily by tourists from all over the world. The caves, which were hand-carved into the rock over a thousand years ago tell a story of resilience and survival of my paternal bloodline. When I saw the caves for the first time, my skin shivered. I recognized it with my whole body as if I’ve been there before, yet I have never laid my eyes on it.

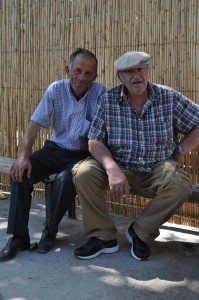

We were welcomed by the village’s school and together we planted apricot trees in the school’s yard with Armenia Tree Project – a symbolic gesture of love for my roots. The school was small and the kids looked happy and beautiful in their adorable uniforms. The Principal of the school, Valentina Balayan, was smiling with pride that she picked out the uniforms. After a brief coffee break at the school the elders of the village took us to the Old Khndzoresk, lower in the canyon, carved into the side of the mountain. This was the original village, abandoned for better housing in 1950s. Earlier my father told the villagers that he remembered playing with a little boy named Hovik in the old village. On the way there, the village mayor phoned someone and the friend my father remembered showed up to greet us. They had a great time talking about their childhood summers together.

We took the Khndzoresk hanging bridge down to see the old village where my grandfather grew up. We did this twice, an amazingly terrifying at first and yet not so terrifying experience. I didn’t slow down enough to appreciate the view from the hanging bridge to the villagers’ hilarious jokes at my expense. The trip across the bridge was worth it. These artificial caves that are over a thousand years old were surreal and walking through the village was a life-altering event. The village elders fed us a delicious feast of traditional khorovatz and I tried to take in the clean, intoxicating air of the region as much as I could.

The hospitality and sincere affection we felt from the people of Khndzoresk makes me proud to belong to them. The village mayor, Sergey Hayrapetyan, was wounded in Karabagh, and so were many of the villagers. During the Karabagh War, civilians defended the village from Azerbaijani military advances and won. The words I can try to use to describe the pride they feel in their homeland would not do it justice. There were no words in Khndzoresk; just love and appreciation from them for my work in the United States for Armenia and Artsakh, and from us for their efforts in defending of our land and preserving our history.

I left Khndzoresk smiling with an expanded family circle. But there was no time to process it emotionally because we were on our way to Artsakh—where the independence movement of the free civilians sharply shifted the trajectory of my peaceful childhood through Azeri crimes against humanity and uprooted my entire life. I wanted to see it for what it was, and once again I was left in awe.

***

What I didn’t understand about Artsakh was made clear once the car passed the checkpoint on the border with Armenia. It was hard to feel it through photos and stories. When I fight for Artsakh, I fight for my people. But when I stepped onto its soil, it was clear to me that the land was humming through me, speaking to me as it did for hundreds of generations of my people. There was something majestic about it and while I heard this said about Artsakh and Syunik before, I never took it too seriously, until the moment I experienced it myself, in my veins, both in Khndzoresk and in Artsakh.

Our guides, Saro Sarksyan and Yervand Hajiyan, took us to wonderful places in Stepanakert and Shushi, and spoke of the history and infrastructure before and after the war, and of the people that live here now. But the land spoke so much more. Aside from its beauty and richness, the land is connected to Armenians, and many people we met spoke of this connection. That is why thousands of Baku Armenians came to Artsakh after the ethnic cleansing in Baku and fought in the war for its independence. This is the reason why I met so many Baku Armenians at my event in Stepanakert who were proud of the accomplishments that their country, the Nagorno Karabagh Republic, had achieved in the last two decades.

Life is hard for Artsakhtsis, there is no doubt of that. Jobs are scarce and pay little. They are isolated from the rest of the world not only because of the irrational blockade imposed by Azerbaijan, but also because of the threat of military attacks on its airport and its civilian airplanes by the Azerbaijani government. You can still see the damage of the war as you drive through the city of Shushi and in some sections of Stepanakert. But the obliterated cities are rebuilding. Stepanakert is absolutely gorgeous. Shushi is full of life and activity. People spend their evenings outdoors, walking in pairs or sitting on benches while the children play in the parks. Many people, including Baku Armenians, own businesses and are settled there. New schools have been built, and little kids in their pristine new clothing and shoes have no concept of the war-torn streets like their parents do.

The most significant message I received from Artsakh residents—unanimous and consistent—was that they are their country, every single one of them. The message wasn’t confrontational or aggressive, just calm, positive, and a matter of fact. Nothing will take them away from their ancestral land; nothing will tear it apart again. Their sons and daughters are guarding the border just like their parents did in their youth. No one but they will govern their land, no matter what anyone says outside of its borders. The democracy and transparency of its government is the love they pour into the country through a long struggle to overcome aggression, war, and oppression.

The Artsakhtsi spirit is strong and independent; after all, they defeated the Azerbaijani military with hand-designed and hand-made weaponry. But they are not too proud to value the work people are doing around the globe on their behalf. The appreciation and love I received from the people of Artsakh will fuel my continued efforts toward recognition of Artsakh’s independence. The faces of the Armenian children reaffirmed why I decided to go public with my story and my diary: The children of Artsakh deserve a future just like any other child of the free world, and I am not going to stop until it happens.

***

To say that my experience returning to Armenia and Artsakh was life-altering would be an understatement. Every Armenian who goes to Armenia has his/her own spiritual connection to the land. I believe mine was severed, over and over again, by the history of the region and the tragedies within my family: first, in 1915, when my grandfather fled the Syunik region to Baku; then again when his family was the target of ethnic cleansing in Baku in 1918 and had to travel to Turkmenistan; and then within my lifetime, when we fled Baku and left for the United States in 1992. But a loving mother always welcomes her child back, and I’m thankful for all the love I have from her despite our fractured history.

My reactions of the two weeks in Armenia and Artsakh are of someone who hasn’t seen the country in two decades. Some may argue it’s not enough to gauge progress. I disagree. I think it’s easy to miss progress when trips are frequent and gratification isn’t instant.

It is also incredibly easy to fall into the trap of complaining about Armenia and her “backwardness,” which is understandably frustrating, especially for someone who grew up in the West. I lived in Armenia in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. What I have seen is monumental, in both the voices of the people and the structural changes within the country. Let me emphasize to you just how miniscule two decades are in building a strong nation after a history of genocide, war, and independence from the Soviet grip. It will take several generations to weed out corruption and the Soviet mentality, and to build up the economy. It will take people of Armenia, supported by the global Armenian nation, to push the country forward, an inch or two at a time.

We don’t have the luxury of oil, but we have a global network of Armenians—a powerful force to reckon with. Our enemies wait for any opportunity to destroy Armenia.

They want to establish cracks between Armenia and its diaspora, especially to maintain the separation between global Armenia and Baku Armenians and to silence the personal tragedies these families endured at the hands of Azerbaijan. I’ve seen this strategy of divide-and-conquer with my own eyes and I’m beginning to see it backfire. Any time the Azerbaijani government spreads lies around the United States, for example, you can guarantee the Baku-Armenian community will come to their legislators to speak the truth. And they are only getting stronger as time goes on, and the Armenian Diaspora needs to recognize this. Our unity is vital to our motherland’s survival, one decade at a time. And our motherland will always wait for her children, despite the time and pain.

The post Baku to Yerevan: My Voyage Home, Despite the Pain appeared first on Armenian Weekly.