Special for the Armenian Weekly

Knowledge of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941 is etched into the American psyche. Less known are the simultaneous attacks on the Philippines, Hong Kong, the Straits Settlements, the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), and within a week, Burma (Myanmar). Even more obscured is the devastating impact the ensuing Japanese conquests in Southeast Asia had on the Armenian communities there. The largest of those had been thriving in Singapore, the Dutch East Indies, and in Burma. None ever recovered, as this article will show.

Readers may be surprised at some of the Armenian surnames that will be mentioned. Most of the Armenians who came to Southeast Asia were Persian Armenians, and many had been educated in Calcutta. Their surnames were thus Anglicized. For example, Yedgarian became Edgar, Setian became Seth, and Hovakimian became Joaquim.

On Dec. 8, 1941 Japanese troops landed in northern Malaya and began to battle their way south towards Singapore. Despite fierce opposition, they proved unstoppable and crossed the narrow causeway to the island of Singapore on Feb. 8, 1942. After intense fighting and bombing, Singapore, once dubbed the “impregnable fortress,” surrendered on Feb. 15.

The community of some 95 Armenians, augmented by refugees from Hong Kong and Malaya, faced great uncertainty. Armenians had settled in Singapore since the early 1820’s. Some were classified as British as they were born in a British colony. Others from Persia had become naturalized British subjects. Thus the fate of most was sealed once Singapore surrendered. What befell the Armenian community was a microcosm of the larger British community.

With surrender inevitable, women and children joined the frenetic rush for travel documentation that would enable them to leave Singapore. They met with diverse fortunes. Kathleen Seth, Sarah Joaquim, along with Ida, Hazel, Norma, and Maurice Johannes were evacuated to India. Others including Marie and Josephine Joaquim family were lucky enough to get passage on evacuation ships to Perth, Australia. They joined other evacuees in the suburb of Cottesloe. Mary Catchatoor, along with those who fled to family in Surabaya in the Dutch East Indies, were not so fortunate: They ended up in camps. Regina Anthony, aged 85, and her daughter Barbara Teeling were on board the Giang Beesunk by the Japanese off Banca Island; they died at Palembang camp in 1942. Regina’s other daughter, Catherine Dyne, and her 10-year-old son Henry had left on the Mata Hari, which surrendered to the Japanese; they found themselves in the Palembang camp, but survived. Mary Joaquim and her daughter Frances no doubt counted their blessings when they made it to shore on Pom Pong island after their vessel, the Kuala, was bombed by the Japanese on Feb. 14. They were picked up by the Tanjong Penang only to lose their lives when it was attacked and sunk three days later.

At least 23 of the Armenians who could not escape the island were interned in Changi Prison. After the Japanese opened the Sime Road camp for women and children, seven Armenians were sent there. Three died: brother and sister Galstaun and Désirée Hacobian, and their 76- year-old grandmother Mary Anna Martin.

Men joined the Straits Settlements Volunteer forces, and seven ended up as POWs in Changi. Thomas Joaquim had earlier joined the Leicestershire Regiment. This 19-year-old officer fought the Japanese from their landing near Kota Baru all the way down the Malay Peninsula and over to Singapore. There, he was taken prisoner, the moment being captured in a widely disseminated surrender photograph. After the war, his father Basil tried in vain to discover Thomas’s exact fate.

Phillip Seth and Andranik Edgar were sent as slave laborers to the infamous Thai-Burma railway. Like thousands of others, they succumbed to inhumane living and working conditions. Andranik died from gangrene and Phillip from typhoid. Andranik’s memorial plaque rests in the Thanbyuzayat War Cemetery in Burma, while Phillip’s lies in the Chungkai War Cemetery in Thailand.

In Changi, Mackertich Hacobian, formerly a deacon in St Gregory’s Church, helped form an ecumenical group. He lectured fellow internees about the Armenian Church and wrote a book that was later published as The Armenian Church: History, Ritual, and Communion Service. His eldest son Steve produced a collection of pencil portraits of important internees. Although these were compiled into a booklet, it was never published.Two other prisoners of Armenian descent stand out. Kenneth Seth, later to become a prominent lawyer in Singapore, risked his life to hide a radio and pass on news. Gordon van Hien (of the Paul family) was later awarded an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) for his work in maintaining camp moral by forming an orchestra and choir.

A handful of Armenians who held Persian passports escaped internment; they were given armbands classifying them as neutral. At times the distinction seemed arbitrary, as some born in Singapore were lucky enough to be deemed neutral. Martyrose Arathoon, who held dual citizenship, used his Persian passport to avoid internment for himself and his family. He later earned the wrath of the British authorities, who angrily withdrew his British citizenship. This decision was overturned by a judge who ruled that in war, one had to be pragmatic.

Those who survived the camps were sent to England or Australia to recuperate. Gradually families regrouped—the Johanneses, Martins, Hacobians—but they realized they had better futures elsewhere and left Singapore. It was mainly the elderly who remained.

The Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator, the parsonage, and church grounds were damaged in the war. British field artillery units occupied the church grounds, thus attracting enemy fire. Looters stole irreplaceable treasures, including the priceless Bible, hymnbooks from the 1850’s, and prayer books printed in 1846. After the war, the Martin family bore most of the repair costs, but no permanent priest was appointed.

Turning to the Dutch East Indies, it surrendered to the Japanese in March 1942. There were about 500 Armenians living in the colony, mainly in the commercial city of Surabaya. Others lived in the capital Batavia (Jakarta), in Macassar, Bandung and elsewhere. The Dutch and other Europeans were quickly rounded up and interned. Armenians were among the thousands of civilian internees. In Surabaya, a small number of them remained free allegedly by a quirk of fate. The late Mackertich Martin recounted that two Armenians had worked for the Japanese before the war, and thus were imprisoned by the Dutch when the war broke out. Released by the Japanese, they were questioned by the Japanese governor who was curious about them. On hearing their history, he apparently advised them to change their nationality on their identity cards to Armenian. Those who did so were allowed to remain in their homes. The rest were imprisoned, suffering alongside other internees in notoriously bad conditions in camps at Cimahi, Bandung, and Malang. Memoirs of the survivors give horrific and heart-wrenching accounts of deprivation, starvation, disease, beatings, torture, and death.

At least 40 Armenians died in Japanese internment camps on Sumatra and Java. They included Marcar David and Thaddeus Galestan. Others (for example, Lucas John, an invalid, and his son Harold) died in Surabaya prison after brutal interrogations. Manuel Petrossian was beheaded by the Japanese, while Charlotte and Flora Martin were murdered by them. The end of the war did not mean the end of killings. At least eight Armenians were killed by Indonesians in their struggle for independence from the Dutch. While Ara Sarkies died in Cimahi Camp in 1945, his brother Albert survived, only to be killed by Indonesians in October 1945. The same fate awaited Arsen Zorab and his brother Joseph. The brutal treatment endured by some led to their deaths—at home, in the hospital, or en route to Europe.

The late Armen Joseph, an Armenian researcher who survived internment, estimated that 10 percent of the community had perished, while the late Elias Ellis suggested 13 percent. The survivors were sent to Singapore, then on to Australia, Britain, and the Netherlands to recuperate. Very few settled back in Indonesia; instead, they made their homes in Europe, the United States, or Iran. It was the end of the Armenian community in the Dutch East Indies, which could trace its genesis to the 1640’s. The individuals who perished are not forgotten. The Dutch War Graves Foundation has commemorated each with a white cross in remembrance cemeteries.

The roll call of victims’ family names includes Apcar, Arathoon, David, Gasper, Johannes, John, Lucas, Martin, Michael, Minas, Peters, Sarkies, and Zorab, names repeated in Singapore and Burma.

The third country where Armenian communities were devastated by the war was Burma. Armenians had been trading and residing there since the mid-1500’s. Those early merchants had come from Armenia, but from the 1800’s, arrivals were mainly from Persia. Records suggest that at least 300 Armenians and their descendants were living in Burma in 1941. Most resided in Rangoon (Yangon), but others lived in Maymo and Mandalay.

After the Japanese attacked Burma in mid-December 1941, and captured Rangoon in early March, there was little chance of escape by sea or air. The only way out was a long and dangerous overland trek into India. Over 200,000 residents, mainly Indian, British, and others including Armenians, saw this as their only hope of survival.

Their gradual exodus is often referred to as the Trek. Ill prepared for its physical rigors and dangers, more than 4,000 refugees died of exhaustion, accident, disease, and starvation. They had cut paths through the jungle, forded flooded rivers, picked their way along treacherous mountain paths, battled leeches, snakes, and malaria, and even fallen to attacks by tribesmen. For safety, they traveled in small groups of family and friends. The shorter East-West route route to Manipur took up to several weeks. The longer and more dangerous northerly route up the Hukawng valley and over the Chaukan Pass lasted up to three arduous months. Some exhausted trekkers arrived more dead than alive in India. Indeed, a few died from their ordeal after reaching India.

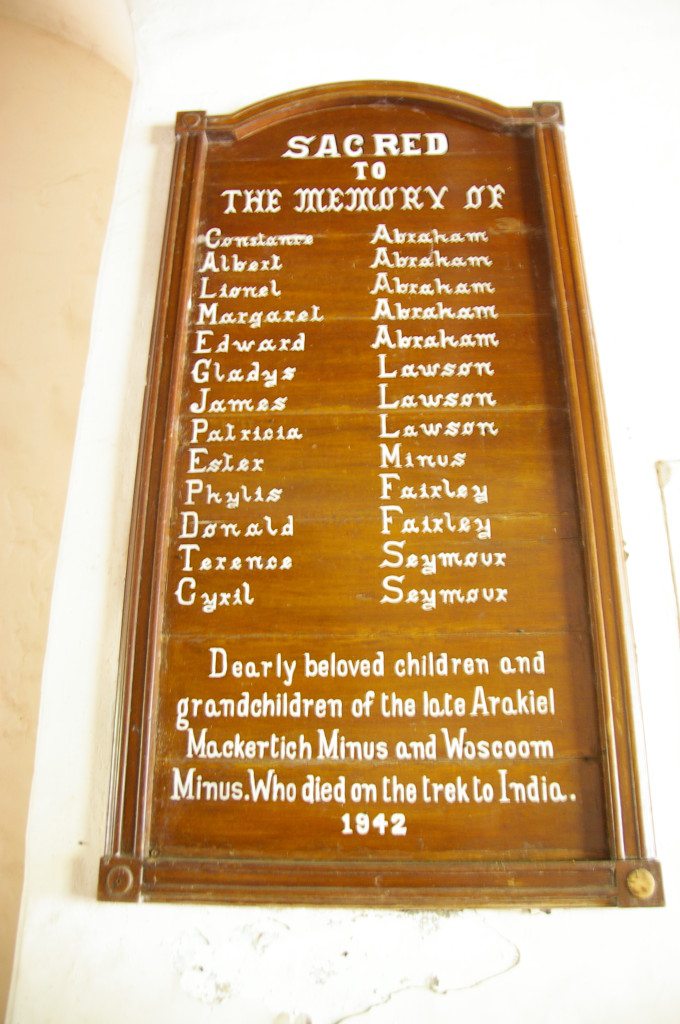

The evacuation lists collated by the Anglo-Burmese Library shows at least 75 Armenian family names among the evacuees. Sadly, another 32 family names are listed among the dead, while another 25 were interned. The names are familiar to the region and include Apcar, Aganoor, Chater, Emin, Gasper, Gregory, Johannes, Minas, Shircore, and Vertannes. Epitomizing the terrible losses to individual families is the plaque in St. John’s Church in Yangon, which commemorates seven members of the Minus family who perished on the Trek.

The stories of the Armenians who suffered under Japanese occupation, like those of all victims, are tragic, grim and thought-provoking. What happened to the Armenians in Singapore, Surabaya, and Burma was replicated on a smaller scale in the communities in Hong Kong, Shanghai, Tientsin, and Harbin. A few sentences cannot do justice to the sufferings of those victims. Some survivors spoke little, if at all, of their ordeals. Their descendants are uncovering glimpses and gradually new information is emerging that will allow a more complete picture of the Armenian war victims to be created.

Poignant stories of survivals and deaths, as well as other details, can be found on the following websites: the Malayan Volunteers Group at www.malayanvolunteersgroup.org.uk; the Netherlands War Graves Foundation (Oorlogsgravenstichting) at www.ogs.nl/pages/home.asp; the Anglo-Burmese Library at www.angloburmeselibrary.com/lists.html; the Commonwealth War Graves Commission at www.cwgc.org; and the Changi Museum and Chapel at http://www.changimuseum.sg.

See also the book Respected Citizens: A History of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia by Nadia Wright.

The post Fallen but Never Forgotten: Armenian Victims of the Pacific War appeared first on Armenian Weekly.