Special for The Armenian Weekly April Magazine

A personal memoir

Four score and 15 years ago, “Ravished Armenia” (or “Auction of Souls”), the silent movie where Aurora Mardiganian (1901-94) played her own story of survival of the Medz Yeghern (Great Crime), came onto the silver screen as the earliest example of a genocidal crime embedded into a Hollywood production. The outcome was not very enlightening, as film historian Anthony Slide, one of its most knowledgeable students, has argued: “Despite the high moral tone surrounding the production (…) it is obvious that ‘Ravished Armenia’ was really nothing more than a carefully orchestrated commercial production.”1

Clik here to view.

La Razon, Buenos Aires, August 31, 1920 (Photo courtesy of Eduardo Kozanlian)

Nevertheless, its PR impact as “a frank straight-forward exposition of sufferings of Armenia, which makes a sincere and powerful appeal to every drop of red blood in America’s manhood and womanhood,”2 as well as its vanishing from worldwide film vaults—a metaphor of the wall of silence that for decades surrounded the wholesale extermination—have aroused widespread interest.

The story had already caught my eye as a high school senior in Buenos Aires. My father had a few collections of Armenian newspapers, including the independent Armenian Argentinean biweekly Hamazkayin (1964-68, in Armenian and Spanish), where the early Spanish translation of Aurora Mardiganian’s story was serialized in 1965. Years later, a very informative article by Armenian-American book collector Mark A. Kalustian in The Armenian Mirror-Spectator helped complete the picture.3

After some time, I passed the article on to a friend of mine, Eduardo Kozanlian, who had been hunting down all sorts of Mardiganian-related materials for a very long time. Seventy-five years after the first screening of 1919, he discovered the surviving fragment of approximately 15 minutes. One night in 1995, in my Buenos Aires home we watched those silent images that had once tried to represent the Aghed (Catastrophe). Over the years, I would urge him to write down an account drawn from his extensive collection of memorabilia, but, for different reasons, it never happened.

Attorney Siruhi Belorian-Piranian in 1999 sponsored a reprint of the Spanish translation of “Ravished Armenia” in Buenos Aires on the 80th anniversary of the first edition. Kozanlian loaned his own copy and provided pictures and other materials. He was asked to write an introduction to this second edition, but for unknown reasons and without further explanation, the text was dropped from the final printing.4

In late 1996, Kozanlian had traveled to the United States to pursue his research. He presented VHS copies of the film segment to people interested in the subject or who had helped him in his endeavors. Anthony Slide was likely referring to those copies in 1997 when he wrote, “Rumors abound of a videotape representing 10 percent of the production circulating in the Armenian-American community.”5

One of the copies was probably “pirated” for an anonymous VHS commercial release of the segment circa 2000, without identification of publisher, place, or date; I saw it on sale in 2002 at the Sardarabad bookstore in Glendale, Calif. The back cover of the jacket only mentioned “a researcher in Buenos Aires, South America.” Some footage appeared in Andrew Goldberg’s PBS documentary “The Armenian Americans” (2000), which included Kozanlian’s name among the credits, but did not identify the movie as the ultimate source.6

There was no reference to the story in the DVD released in 2009 by the Armenian Genocide Resource Center of Northern California, spearheaded by late genocide researcher Richard Diran Kloian (1939-2010). It included the fragment cleaned up, edited, and captioned after the titles of the book, with Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” as background music—the same music of the VHS—and the addition of a slideshow of the stills. Filmmaker Zareh Tjeknavorian’s “Credo,” a 22-minute video of the film together with Armin Wegner’s photographs from the genocide, footage of the 80th anniversary of the genocide in Yerevan, and the music of Loris Tjeknavorian’s “Second Symphony,” was uploaded on YouTube in April 2009. The accompanying note stated: “Incredibly, all copies of ‘Ravished Armenia’ were lost until a 15-minute fragment resurfaced in France in the 1960’s. The reel was preserved by a cinematographer named Yervand Setyan, and is presented here in full.”7

As the second Spanish edition of 1999 was out of print, researcher Sergio Kniasian in 2011 published a digital version of the Spanish translation on a CD, which also included his article on the discovery and another by film scholar Artsvi Bakhchinyan on early cinematography on the genocide, together with many illustrations.8

I revisited those silent images in April 2010 at the screening of the DVD in St. Leons’ Armenian Church of Fair Lawn, N.J., and talked about the discovery during the question and answer session that followed Anthony Slide’s lecture. Upon his request to write down the story, I started to draft an article that would include other pieces of information I had uncovered over the years.9 The 20th anniversary of the discovery is an opportunity as good as any to write the last word and to set the record straight.

Armenian reception of the film

A few quotes from Armenian-American newspapers in 1919 have appeared in Bakhchinyan’s encyclopedic study of Armenians in world cinema.10 Otherwise, those collections do not seem to have been scrutinized by researchers of “Ravished Armenia,” at least in the United States. There were very few English-language newspapers—Arshag D. Mahdesian’s The New Armenia, an independent monthly, and The Armenian Herald, a monthly briefly published by the Armenian National Union. Party organs published their newspapers in Armenian: Hairenik (Armenian Revolutionary Federation, or ARF) in Boston; Azk (Armenian Constitutional Democratic Party), the predecessor to the now defunct organ of the Armenian Democratic Liberal (Ramgavar) Party, Baikar, also in Boston; Yeridasart Hayastan (Social Democrat Hunchakian Party), in Providence at the time; and Asbarez (ARF), then in Fresno.

Apart from a few other short-lived publications in Armenian, whose collections are more difficult to trace, we must make particular mention of Gochnag (renamed Gochnag Hayastani in 1919 and Hayastani Gochnag in 1921), published by the Armenian Educational Foundation in New York, which represented the views of the evangelical section of the community and widely supported charity work, particularly by the Near East Relief, which was presided over by missionary James L. Barton, under whose auspices the book had been published and the story filmed. A search of the collection of this weekly between November 1918 and May 1920, nevertheless, did not yield references to Mardiganian’s book (of which two American editions were released in 1918-19), or to the movie, which was premiered at the Plaza Hotel of Manhattan in February 1919 as “the official photo-drama of the National Motion Picture Committee of the American Committee for Relief in the Near East.”11 Such a glaring omission is odd; the promotion of the film claimed that “although it is probably the most sensational film ever produced, the best people, including churches, in every community, are giving it their unqualified support because of its overwhelming truths.”12

Clik here to view.

La Nacion, Buenos Aires, August 29, 1920 (Photo courtesy of Eduardo Kozanlian)

Only a brief report of the screening of the film in Worcester, Mass., on June 2, 1919 appeared out of the blue. Even today, a reader unaware of the existence of the film would not realize that it alluded to it. The report noted the “presentation called ‘Ravished Armenia’ that depicts the Armenian misery, whose heartbreaking scenes could not awaken but sad feelings in the hearts of any Armenian. Watching those images representing the calamitous state of our sisters, s/he seemed to hear a voice in his/her soul, the voice rising from the wounded hearts of thousands of miserable Armenians who called for help.” Fourteen Armenian young girls wrapped in Armenian and American flags—their names were listed—served as ushers and worked in the fundraiser that followed. Another young girl played the piano.13 The word nergayatsum (literally “presentation”) may also mean “performance,” “play,” or even “exhibition,” and ‘Ravished Armenia’ could be taken for a slideshow of photographs of the Medz Yeghern.14

A cursory and partial look at the issues of Hairenik, Azk, and Yeridasart Hayastan has not revealed negative reactions from the community. Nevertheless, there were reports about problems of censorship due to the graphic nature of the images on the eve of the commercial release (May 1919):

“To make ‘Ravished Armenia’ a source of profit, its moving picture [շարժուն պատկեր] was made to be exhibited. The New York newspapers devoted wide pages to it and confessed that no moving picture leaves such a horrifying impression as ‘Ravished Armenia’ does; judging from the images that have been brought out, we admit that these moving pictures invited more compassion and pity than the descriptions of ‘New York American.’15 Today, however, the government has set a prohibition and does not allow the moving picture ‘Ravished Armenia’ to be exhibited, because many girls and women could not contain their shock during the showing and fell and fainted. How should we not remember here and ask: What happened to those who were the spectators and the unfortunate subjects of all that? Of course, we cannot say with certainty that the cause of this suspension is emotion or some political motive. This will be known in the future…”16

Mardiganian’s story during and after the production of the movie mixed stardom and exploitation. According to Slide, who explored the issue in detail and was fortunate to interview her in 1988, “No more sorrowful exploitation by the film industry of a tragic event in world history exists than that of the filming of ‘Auction of Souls.’”17

It is not known, however,that the community actually took an interest in the young survivor’s troubles and tried to help her. We have at least one documented reference from the Armenian National Union, an umbrella organization founded in 1917 in Boston to pursue the Armenian Cause. This was a branch of the homonymous organization founded earlier that same year in Egypt as the outcome of an inter-party agreement. It was initially comprised by six main organizations: two churches, the Armenian Apostolic Church and the Armenian Evangelical Church; three parties, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, the Social-Democratic Hunchakian, and the Reorganized (Veragazmeal) Hunchakian (the 1896 splinter that became one of the founding parties of the Armenian Democratic Liberal Party in 1921); and a charity, the Armenian General Benevolent Union. Divergences arose within the organization in the beginning of 1919, after the all-community vote to elect delegates for the Armenian National Congress held in Paris the same year. As a result, first the ARF and later the Hunchakian Party left the Union.

The Union lobbied to stop the exhibition of “Auction of Souls.” The whereabouts of its files are unknown to us, but fortunately there is a copy of its four-year report (1917-21), published in Armenian. It contains the following paragraph: “The Union worked to suspend the performances of the photoplay [պատկերախաղ] ‘Ravished Armenia’ or ‘Auction of Souls,’ shown to the benefit of the American [Near East] Relief everywhere in the United States, whose features hurt Armenian feelings.”

A footnote to the paragraph clarified: “An Armenian girl who was the main actress of this photoplay had come to America and was being exploited. The known chemist, Dr. Moosheg Vaygouney18 [Մուշեղ Վայկունի], came from San Francisco to New York to make the same protest to the American Relief, both to stop the movie and the exploitation of the girl.”19

This may have not been the only case of opposition and outrage. An article by Karekin Boyajian in Hairenik spoke of an unnamed film, promoted throughout the community as a depiction of “the real picture of the Armenian tragedy.” Three people had protested to the Armenian Prelacy, while others had been a hindrance to the screening: “However, the exhibition of the images…did not give the real value of our national profile and moral principle. … In their dishonest role of exploitation, the Armenian members of the Armenia Film Company came to our wounded hearts to open new wounds. … Shame on such Armenians, who wanted to show once again to [the] Armenian and foreign public the Turkish impudent barbarism on our virtuous sisters’ honors.”20

Quoting these excerpts, published in April 1921, Bakhchinyan has suggested that the article may have referred to “The Hero of Armenia,” a film with Armenian national hero General Antranig as the main character (and seemingly containing real footage of him), produced by Armenia Film Company. The announcements in the press that the film, otherwise unknown, was ready in April 1920 did not make any mention of genocide scenes, though.21 It is also possible, then, that the company actually rented and showed “Ravished Armenia” to make a quick buck, as the vague description seems to fit Aurora Mardiganian’s film better.

Negative reactions, which need to be further explored, were likely motivated by the realization that, “while the text tried to sanitize the brutalities of the Turkish gendarmerie, the film went as far as to deliver a sensational exposé of sexual transgression that objectified women and girls, thus downplaying the gravity of the committed crimes.”22 The infinite violence of the Medz Yeghern had broken all moral standards. The exhibition of such scenes was seen as a continuation of that violence.

‘Ravished Armenia’ in Buenos Aires: 1920s

Mardiganian’s memoir had reportedly reached 360,000 copies in circulation by 1934.23 It was translated twice into Armenian before the release of the movie, and serialized in Hairenik and Yeridasart Hayastan, but none of those translations were turned into a book. Both were published in 1918, after the serialized version in the Hearst newspapers and not after the book, whose first edition was in December 1918.24 Other translations would be published in book form much later, in the 1960’s (Western Armenian) and 1990’s (Eastern Armenian).25

It seems that the second edition of the memoir was simultaneously reprinted and translated into Spanish, as both publications were printed in 1919 by International Copyright Bureau, a literary agency based in New York. The Spanish translation bore the title “Razed Armenia. Auction of Souls. The Story of Aurora Mardiganian, the Young Christian Girl Survivor of the Terrible Massacres.”26 There was a subtle change in the title: while the English ravished presented a double meaning (“raped,” in the usage of the day, now old-fashioned, or “damaged and robbed,” also today), the similarly sounding Spanish arrasada plainly meant “razed” or “destroyed,” without any sexual connotation.

A Spanish translation of an English book outside of Spain and Latin America was not a surprising event, even a century ago. There were also precedents of Spanish translations of French books published in Paris. As far as we know, this was actually the third translation on the topic in Spanish. The previous two such translations, Arnold Toynbee’s Atrocities in Armenia (1916)27 and Faiz-el-Ghusein’s Martyred Armenia (1918),28 were published in Great Britain.

The movie reached Latin America and was shown in Mexico, Cuba, and Argentina.29 Its title, “Subasta de almas o Armenia arrasada,” was a combination of both Spanish titles of the book. It was premiered in the Callao Cinema of Buenos Aires on Sept. 1, 1920. Advertisements appeared in the dailies La Nación and La Razón, and there were likely others. After the title of the film, the ad in La Nación quoted a lengthy paragraph from the book—the scene where a blonde girl delivers herself to the soldiers, in vain, to try to save her mother—followed by a picture of a crucified woman (suggesting that the girl was her) and the conclusion: “Aurora Mardiganian, the Christian young girl surviving among so

many undefended women, narrates scenes like this, which the public may learn watching the film…”30 An ad in another newspaper, La Razón, published the day before the premiere, highlighted that the film was a “remarkable cinematographic work which recounts the sad story of Aurora Mardiganian, the Christian young girl miraculously saved from death, who in the book Auction of Souls, dedicated to all parents, says (. . .).” The same picture of the crucified woman was interposed, with a quote from the memoir, a note on the movie theater and the date of release, and mention that the film premiered in New York at $10 per ticket and that Mardiganian herself was the protagonist. The distributor of the film, Manuel Sáenz, and his address were also given.31

Unfortunately, we know nothing about the echoes of the film. Besides, there were no Armenian newspapers to chronicle any reaction from the community. La Nación, after giving a summary of the film in its column on new movies, had concluded before the premiere: “It is, then, the story of a true scene that serves as plot to the whole history of Armenia. And the film can be judged only with it. In its scenes, in its various episodes, one must see the development of a document which is the protest of an oppressed people.”32

The print of the film was still available in 1926, when the Buenos Aires chapter of the Armenian General Benevolent Union organized a screening.33 The minutes of the board meeting of July 21, 1926 recorded: “Although the board had decided to organize the performance of a play, due to the absence of an appropriate script, it decided to make a contract with a cinema to show two films from Armenian life: ‘Miss Arshalus [sic] Mardiganian’ and ‘Oriente.’” The minutes do not mention who owned them. After various inquiries, they finally found a movie theater in the neighborhood of Boca, the Teatro José Verdi, quite close to the Armenian-populated areas of the city, and rented both films, “Subasta de almas” (60 pesos) and “El Oriente” (80 pesos); the name and origin of the latter, as well as its actual relation to Armenian themes, is unknown. The minutes from Sept. 29 noted, “Both films being sad ones, it was decided to rent a comic one too.” The screening was scheduled for Oct. 24, and 800 tickets were put on sale.

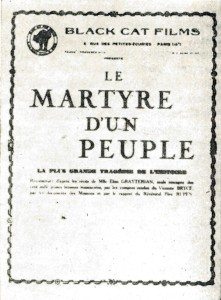

Clik here to view.

French brochure about Le martyre d’un peuple

Unfortunately, we do not have any further information about the event, or the reaction of the public; a few short-lived newspapers existed in the community between 1922 and 1925, but 1926 marked a gap in the history of the press. The Armenian-Argentinean community at that time, unlike its North American counterpart in 1919-20, was mostly made up of newly arrived people who, after enduring the genocide, had escaped either the massacres of Cilicia in 1920-21 or the catastrophe of Smyrna in 1922. The Argentinean weekly Caras y Caretas wrote in 1923 that they “only speak of war, of crimes, of fires, of deportations, of political assassinations, of the death of Enver Bey or Talaat Pasha…and find in these red themes their favorite conversation, while the children entertain themselves playing incendio [fire] in one of the corners of the house.”34

‘The Despoiler’ and ‘Châtiment’

In a book on the 100th anniversary of the first Armenian movie, Bakhchinyan called attention to “The Despoiler,” a film by American director Reginald Barker (1886-1945), with screenplay by J. G. Hawke and famous actor-director-screenwriter-producer Thomas H. Ince (1882-1924), “which reflected the tragic events and episodes of Armenian resistance” and whose scenes “took place at the Turkish-Armenian border.” It was filmed in August-October 1915 and released by Triangle Film Corporation in the United States on Dec. 15 of the same year.35 This film had a very intriguing and trouble-ridden history, which has not been entirely clarified.

“The Despoiler” (also registered as “War’s Women”) had a pacifist tone, the same as Ince’s important anti-war movie, “Civilization” (1916), which he co-directed with Barker and others.36 It ran into problems with censorship from the beginning: 10 days after its release, on Dec. 24, 1915, George H. Bell, the commissioner of the New York Department of Licenses, judged the film to be “indecent, immoral, contrary to public welfare, and not fit to be exhibited in a licensed theatre.”37 The screenings ended in late January 1916; the film was sold to the Fulton Feature Film Corporation (a subsidiary of the Triangle), re-issued in early 1917 in a revised version due to an injunction by the New York State Court on charges of immorality, and re-released in January 1920 as “The Awakening..” Barker established his credentials as a daring filmmaker: “‘War’s Women’ was in effect banned because of its perceived attitude toward sex and sexuality but it was as much a film sending out a message about female liberation and social, political, and cultural freedoms about to come, as it was a movie designed purely for titillation.”38 However, the synopsis does not show any Armenian connection. In war-torn Europe, Colonel Damien (Charles K. French) seizes an enemy town and the Emir of Balkania (Frank Keenan), the commander of the supporting native troops, threatens to unleash his men on the women who are staying in the town abbey to persuade the defeated soldiers to give up their ill-gotten money. Damien gives the captured men a payment deadline and falls asleep on a chair. Meanwhile, the emir goes to the abbey where Sylvia (Enid Markey), the colonel’s daughter, is secretly staying. He offers to free the other women in exchange for her sexual favors, but she shoots him after complying with his demands. When Damien discovers the emir’s corpse, he orders the assassin shot. Covered by a veil, Sylvia is promptly executed. The colonel is overcome with grief after her body is identified. Finally, he wakes up in his armchair and, realizing that the tragedy was only a dream, orders his troops to leave the town in peace.39

The Armenian connection appeared in the French version of the film, “Châtiment” (Punishment), released in Paris on May 18, 1917. Thomas Ince was introduced as the director, something that happened frequently with films he produced. The critic of the weekly La Rampe wrote: “Ince’s ‘Châtiment’ is a marvelous and poignant film. Ince, a great artist, has given his measure once again. One has to watch ‘Châtiment,’ which represents superbly the bestiality of Armenian persecutions and shows the risk of the Boches in exciting vile passions among the Kurds.”40 The specialized weekly Ciné pour tous, in an extensive article about the productions of Triangle Film Corporation, characterized Châtiment as a film-à-thèse in 1921, writing, “the situations are of rare power and, as always, the many psychological notes on the margin of the intrigue make ‘Châtiment’ much more than a successful drama.”41

It is not clear how and where the film changed setting and plot. The only available copy of “The Despoiler,” shorter than the American original and with some losses, was restored by the Cinemathèque Française in 2010 (a five-minute trailer is available at its website). The fact that the movie was silent allowed the modification of the montage and the title cards. And thus the American original, set in an imaginary European area, with the main villain being a colonel with a vaguely French name, was turned into a realistic film of anti-German propaganda. The Kurdish troops of Khan Ouardaliah, led by German colonel Franz von Werfel, are operating on the Turkish-Armenian border. Both bandits enter Armenia and terrorize Kerouassi. Women and children take refuge in an abbey, while the notable men of the town are arrested; if they do not yield their assets and properties, their women and daughters will be sent into captivity. Beatrice, the daughter of the colonel, who was looking for her father, also reaches the abbey. The blackmail has no effect and von Werfel leaves the abbey spurring Ouardaliah’s rage, who covets Beatrice. The young girl accepts to give herself to the khan, on condition that her unfortunate companions are spared. After the horrible sacrifice, the half-mad girl kills her sleeping torturer with his weapon. Vvon Werfel sends the killer to the firing squad without realizing that she was his own daughter. Guilt-stricken, he spares the unfortunate women and takes his mercenaries elsewhere.42

It is ironic that the name of the German colonel is similar to Franz Werfel’s, the author of The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, who was a soldier in the Austrian army during the war. But the coincidence ends there.

Clik here to view.

Yervant Setian (a.k.a. Cine Seto, 1907-1997)

Film scholar Marc Vernet has recently remarked: “In any case, it does not look likely that the French distributor of ‘Châtiment’ had the possibility of reworking the material of 1915 to update it; it is much more likely that the French version of 1917 comes in fact from the American version of 1917, after the retreat of January 1917 and in the moment of entrance of the United States into the war in April 1917. Basically, the version of 1917, both American and French, just erases a little the self-imposed censorship of 1915 (fuzziness of locations, names, and procedures of the main character who just dreams) maintaining the imposed censorship (the scene judged blasphemous).”43

The film had its name and contents changed for its commercial exploitation in France; there seems to be no evidence that the American original also changed its plot at the time of its re-release as “The Awakening” in 1920. It shows a remarkable parallel with the fate of “Ravished Armenia,” which changed its name and presentation in France some time between 1920 and 1925.

Le martyre d’un people

The first frame of the extant segment of “Ravished Armenia” offers a puzzle that only makes sense for readers of the Armenian language: the title is spelled in Soviet Armenian orthography and has nothing to do with the original film itself. This is a silent reminder of where these fragments were found: Yerevan. The story has a long and fascinating thread.

In October 1988, the Soviet Armenian monthly Sovetakan Hayastan (1945-89), a publication for the Armenian Diaspora by the state-run Committee for Cultural Relations with Armenian Abroad, featured an article by Gevork Mirzoyan in its section, “In the Shelter of the Motherland,” which included stories of repatriates who had successfully lived and thrived. It profiled Yervant Setian (1907-97), a survivor of the Medz Yeghern born in Adapazar, who had worked as a cameraman in Marseilles, France, before settling in Armenia during the post-World War II repatriation, where he continued his career in the Armenfilm studios over the next 30 years, with credits in popular movies like “Aurora Borealis,” “I Know Personally,” “Why the River Makes Noise.” The quotations below are taken verbatim from the translation, which appeared simultaneously in the English and Spanish digests of Sovetakan Hayastan—presumably in other languages, too—called Kroonk. The English publication included the photograph of Setian in his old age, as well as a picture of him in 1945 filming the unveiling ceremony of the statue of General Antranig in the Parisian cemetery of Père Lachaise.

In the summer of 1925, Setian, then 18 years old, watched a film called “Le martyre d’un people” (The Martyrdom of a People) in a movie theater in Marseilles. “To the solemn accompaniment of the piano, scenes of the Armenian deportations and of the unprecedented atrocities they were subjected to were shown on the screen. In the cinema hall, the film aroused the fury of the audience. Not only Armenians but foreigners as well burst into tears and were beside themselves with rage protesting vociferously against the perpetrators of the slaughter,” wrote Mirzoyan. He quoted Setian: “I was filled with thoughts of desire for revenge, which bound [me] more closely to the cinema. I made up my mind definitely to become a camera man.”44

Meanwhile, Black Cat Films screened a double program on May 11 and 18, 1928, at the Omnia-Pathé movie theater of Paris. It included the films “Poupée de Vienne” (The Vienna Doll) and “Le martyre d’un people.”45 The headquarters of this production and distribution company were in the 10th arrondissement of Paris, an area densely populated by Armenians; it had moved from 44 Rue de l’Échiquier to the second floor of 5 Rue des Petites-Écuries on Sept. 15, 1926.46 Its directors were Messrs. Desmet and Malbrancke, who had established a solid reputation and represented six production companies, including Black Cat Films.47 It was listed at the same address in 1931 together with other French producers, renters, distributors, and agents.48

However, in the same way that the plot and location of “The Despoiler” had changed from the United States to France, the plot and the location of “Le martyre d’un people” would change within France, as the commentary of Les Spectacles reflected. The Armenians were replaced by the Balkanic peoples in the Paris screenings:

“We are here in a grandiose evocation of the troubling times when the Balkanic people fought each other to the profit of the third neighbor, who meanwhile grabbed the wealth of the warring people.

“We attend in this Martyre d’un peuple to the massacres that, regrettably, bloodied Eastern Europe towards the middle of the world war. These are authentic documents patiently collected or sometimes reconstituted following the reports of the embassies.

“One has to see this poignant misery, the torments that endure an entire hungry people, dying from thirst, whose residences are robbed, women are kidnapped, and young girls are ignominiously tortured amid the storm, while the little children sow their bodies along the tough road of exile and slavery.

“All the episodes of this vivid tragedy are found in this production of a shocking realism, which the Black Cat Film may feel proud of having in order to show to the people who want peace all unknown horrors that happened in faraway countries, where it seems that civilization should plant less ferments of hate and more happiness for people of good will.”49

Here we have a puzzle. Accepting that Setian had watched “Le martyre d’un people” as an Armenian-related production in 1925, we find that it was turned into a non-Armenian movie in 1928 and, a few months later, it became an Armenian-themed movie once again. The newspaper Aztag of Beirut in January 1929 informed of the screening of «Մարտիրոս ժողովուրդ մը» (Martiros zhoghovurd me, A Martyr People) at the movie theater El Dorado of Marseilles, based on the testimonies of James Bryce and Henry Morgenthau, and “according to the witness testimonies of an Armenian woman who survived the deportations.” The short report noted the absence of identification of both executioners and victims.50 Abaka, another Armenian newspaper based in Paris, wrote in February 1929, probably after another screening, that the film “was a martyrdom, a cumulated and enriched combination of terrible scenes taken from a Life of the Saints or a Synaxarion. It was a true suffering for an Armenian to be present, and a foreigner would have thought how a people allowed such savagery to be enacted over themselves, their women, and children.”51

Yervant Setian, known by the nickname Ciné Seto, went on to film several documentaries related to Armenian community life in France during the 1930’s, including “Faces of Armenian Scientists,” “Memorial of Armenia,” the consecration of the Armenian church of Marseilles, the burial of ARF intellectual Mikayel Varandian, the departure of 800 repatriates to Armenia, and others.52 The silent film era was already history when he stumbled upon a copy of “Le martyre d’un people”: “I used to attend the cine-photo exhibition of Paris held in February every year, and in 1938 as usual I was there. After visiting the exhibition I went to George Miller’s film company. He welcomed me warmly and said: Mr. Setian, I have to inform you about an interesting film dedicated to Armenian life, or to be more accurate to the 1915 Armenian tragedy. I believe you’ve seen it, it’s called ‘Martyrdom of a Nation’ and was shot in England.

I told Miller I had seen it in 1925 and asked him to give me a special viewing. The lights went down and I saw the scenes I had seen several years ago. After the show Miller told me that he had come across the film while putting the old film library in order. He had remembered me. George mentioned the price which was quite a big sum for those years, but you could not bargain with Miller. I did not possess the required amount so I told him I’d buy it in a few days’ time. This treasure could not be lost. I borrowed the money from a Parisian friend of mine and after two days I was with George again. He told me he didn’t have a license to release the film and so it could be shown only in close circles with special invitations. He advised me to take a 16 mm copy from the 35 mm one, to change the title and make some changes in the structure of the film itself. I thanked George and asked him to give me a brochure of the film. A week later he handed me a photocopy of a brochure from the archives, on the front page of which one could see the emblem of the British ‘Black Cat’ Film Studios, then read the following: ‘Martyrdom of a Nation – the greatest tragedy in history,’ and beneath it, ‘This film is shown on the documentary evidence of Eliza Kreterian, one of the survivors of the tragedy of a hundred thousand Armenian girls, as well as on the testimony of Reverend Father Rouben and 1st Viscount James Bryce of England.’ The inside pages contained four stills from the film. Neither the director nor the camera man’s name were mentioned. On the last page only the emblem of the film studio was printed.”53

The Armenian original of the article gave the correct translation of the French original film title («Մի ժողովրդի մարտիրոսութիւնը», The Martyrdom of a People). Nowhere does Setian give any indication of having changed either the title or the structure of the film, as Miller had advised him, or having showed it in France. The war and the German occupation probably prevented him.

Mirzoyan’s article in Sovetakan Hayastan included a picture of the front page of the French brochure, missing from the English translation in Kroonk. The explanatory note beneath the logo of Black Cat Films shows some significant differences with the English-mediated translation, starting from the name of the purported narrator of the story. Most likely, Setian provided a paraphrase in Armenian rather than a textual translation. The short description spells the name of the narrator differently, claims that she was the only survivor of a wholesale massacre of young women (without identifying their nationality), and mentions an additional source:

LE MARTYRE D’UN PEUPLE

LA PLUS GRANDE TRAGÉDIE DE L’HISTOIRE

Reconstituée d’après les récits de Mlle. Elise Grayterian, seule rescapée des cent mille jeunes femmes massacrées, par les comptes rendus de Vicomte BRYCE, par les documents des Missions et par le rapport du Réverend Père RUPEN.

Or,

The Martyrdom of a People

The Greatest Tragedy of History

Reconstituted after the accounts of Miss Elise Grayterian, the only survivor of a hundred thousand massacred young women, through the reports of Viscount Bryce, the documents of the Missions, and the report of Reverend Father Rupen.”54

Miller’s statement that the movie had been filmed in Great Britain made Setian think that Bryce had thrown his influence behind the shooting of the film: “Beyond doubt, only through the efforts of a great and influential statesman could the film studio consent to shoot such a film, which is indeed of paramount importance for us as it is made by a foreign company, a representative of Great Britain at that! But alas, it was too soon withdrawn from the market for which two explanations only could be made; either the studio received a great amount of money from the Turks to destroy all copies of the film, or British Diplomatic Circles ordered its withdrawal. I was glad, however, to be able to save one copy of it and bring it safely to Soviet Armenia.”

Mirzoyan concluded: “Yervant Setian, together with other French-Armenian emigrants, repatriated to Soviet Armenia in 1947. Bringing this and other films to the Motherland, he handed them over to the Yerevan cinedocumentary archives.”55

The discovery of ‘Ravished Armenia’

The year 1988 saw a national awakening with the beginning of the Nagorno-Karabagh movement. Very few people had watched a two-part film that was said to contain documental images of the genocide. The only copy was in the Film Archive of Yerevan, located in the suburban area of the city.

Film scholar Vladimir Badasyan watched the film in 1988 and wrote about it three years later. For unknown reasons, he identified the 20-minute long film as Der Zor, the name of the Syrian desert that had become the ultimate Armenian slaughterhouse. Much of the available information was hearsay: “They say that it is a film of four to six hours of duration. I have to say that I barely believe it. Moreover, I do not discard that we have the entire film, perhaps with some loss of frames. But I have to say that very few claim that what is represented has a documentary nature. I think that even the eye of the non-specialist will realize that most of the scenes are performed.”56 Following Setian’s claim, Mirzoyan had written that the film “combined documentary footage with the testimonies of witnesses who had survived the genocide.”57

It was believed that the film had been shot in the first half of the 1920’s, wrote Badasyan (he gave the date 1926 in the title), and that it was based on the recollections of the young girl seen at the end hanging from a cross; the still was printed along with the article. Setian had spoken about himself and the film in Ara Mnatsakanyan’s 10-minute “Yervand Setyan, 82nd Spring,” released by Hayk Documentary Film Studio in 1988, but without giving further details.58

In 1947, after his arrival to Yerevan, the cameraman had followed Miller’s advice and made a film montage of “Le martyre d’un people” with war footage. Bakhchinyan has quoted two flyers of this newfangled movie, which we assume the cameraman himself wrote—the language is in Western Armenian—and probably circulated among the repatriates; it stated sensitive issues for those times: the film “had been brought out thanks to American Ambassador Mr. Morgenthau and Viscount Bryce of England,” while it also included “the promises of the Allies and the history of the boundaries of Armenia.” Such statements were safe in the period between 1945 and 1947, when the Soviet Union had briefly affirmed its claims towards territories of Western Armenia, now in Turkey. The national awakening of the 1960’s allowed the making of Soviet Armenian TV films about the genocide, which made use of the surviving scenes, the same as Artavazd Peleshyan’s critically acclaimed film-essay, “We” (1967).59

The article in Sovetakan Hayastan makes crystal-clear that Setian never suspected the actual identity of the film he had purchased in France. On the other hand, Badasyan had rightfully noticed that the film was not a documentary. “Le martyre d’un people” was the retitled copy of “Ravished Armenia” and “Elise Grayterian” was Aurora Mardiganian. One may only speculate whether this reconversion was done in England, where the film had been censored and released with cuts in 1920.60

An Armenian from the other side of the world would solve the puzzle. Born in Bucharest, Romania, Eduardo Kozanlian migrated to Argentina in 1952, at the age of five, following the Communist takeover. He found a copy of Aurora Mardiganian’s Spanish book in his father’s library when he was a high school student, at the age of 13 or 14, and was enthralled by the account. Years later, he started to amass a collection of materials related to the book, the film, and their heroine.

He would strike gold during a trip to Armenia in 1994. An academic recommended that he speak with the director of the Film Archive. There he came across the film that Badasyan had identified as “Der Zor,” but the opening frame was different. It showed the date “1915” and the title, in Soviet Armenan spelling, “Հայ ժողովրդի ամենամեծ ողբերգությունը” (Hay zhoghovrdi amenametz voghberkutyune, The Greatest Tragedy of the Armenian People). Setian had apparently merged the original “The Martyrdom of a People” and the description “The Greatest Tragedy of History” of the French brochure.

The first two and half minutes and the last 55” did not belong to the original. Kozanlian compared the remaining 14 minutes with the stills he knew and identified it as part of “Ravished Armenia.” The harrowing scene at the end corresponded to the picture published in the Argentinean newspapers of 1920. The coincidence of this scene with Aurora Mardiganian’s reference to crucifixion in the book—an American sanitized version of actual impalement, as she told Slide61—was a solid confirmation that the segments belonged to the movie, as hers was, as far as we can ascertain, the only such testimony in the extensive bibliography of survivor memoirs.

It turned out that the end of Setian’s story about “Le martyre d’un people” was not what it looked like. His departure from France had actually written a new and fateful chapter in the odyssey of the unrecognized copy of “Ravished Armenia,” as Kozanlian found out when he paid a visit to the 87-year-old former cameraman, who lived with his wife and two children and passed away on Jan. 26, 1997. He told his visitor: “I think that the Istanbul government paid the film production company to burn all the negatives. My rolls were the only remainders. Only this fragment has been conserved.”62

The film had come with him, but never arrived in Yerevan. Kozanlian gave the following version of its fate in an interview during another trip to Armenia in 1999: “When Setian came to Armenia in 1947, he also tried to bring his films. The security service confiscated the cargo in Batum and did not return it.”63 In the same way that religious literature was systematically confiscated, the feared Ministry of State Security (MGB, grandfather of the KGB) would have hardly allowed any politically sensitive material to enter the country.

In an ironic twist of fate, the all but forgotten protagonist of this decades-long search, Aurora Mardiganian, passed away in 1994, the year of the film’s discovery, without even the consolation of seeing a happy end to her tragic story. Two years after her death, Matilde Sánchez, a journalist of Clarín, the most widely read newspaper of Argentina, wrote a three-page essay on the film and its discovery, using materials provided by Kozanlian, as part of a lengthy discussion of the genocide. She noted that oblivion had covered Mardiganian’s trail, and her final paragraph reflected the lack of information at the time about her life after the film: “The journalist admits to being unaware of the actual whereabouts of the exile, who supposedly lived a few years in California, where she had a daughter [sic!] of remarkable similitude to her. But that girl, of course, carried another surname.” Her caveat sounds almost comic when read today: “Unless Aurora was an actress who had loaned her figure for the drama, mounted by the department of Armenian propaganda of the Relief in order to call the attention of American citizens and move the Congress…” Some factual mistakes appeared: The article claimed that Setian had actually recognized ‘Auction of Souls’ after watching the film at the time of his purchase, although no source substantiates that, and that the film, together with other cargo, had been robbed in transit from Batum to Yerevan.64 The two claims were included in the summary that historian Barbara J. Merguerian published a few weeks later in the Armenian Mirror-Spectator, which was translated into Armenian in the now defunct Nor Gyank weekly of California.65

The back jacket of the videocassette released in the early 2000’s omitted Kozanlian’s name and added unwarranted claims: “It presumably lost to history until the year 2000 when a researcher in Buenos Aires, South America, who for years had diligently investigated every lead to find the lost reels, came forward with this surviving 15-minute segment. He related the tragic fate of the film in the 1930’s and 1940’s and how the remaining reels of the rare nitrate based film were truly lost, presumably sunk with a ship on their way to the port of Batum.”66 It is clear by now that the segment was not discovered in 2000—perhaps the year when the anonymous publisher “discovered” his/her source—while the hitherto unheard suggestion that the film had been lost in the sea on its way to the Soviet Union (wrongly ascribed to Kozanlian) may be dismissed; this version leaves aside the basic question of how two fragile nitrate reels survived the shipwreck, while the others got lost.67 Nevertheless, the date 2000 is useful as terminus a quo for the release of the video.

A recent study of the Library of Congress revealed that of the 10,919 silent films produced between 1912 and 1929 in the United States, only 3,313 still exist, including incomplete ones. The reasons given are either the complete loss of material value at the onset of the sound movie era (the studios cleared their vaults and eliminated their original source of wealth) or destruction by degradation of materials.68 There seems to be nothing extraordinary in the apparent total loss of “Ravished Armenia”; foul play—Turkish direct or indirect intervention—remains within the boundaries of speculation. “But just as history can be revised and rewritten, so can films be restored, and rediscovered,” Slide had written in 1997. “Perhaps there is still hope of the resurrection of the film version of ‘Ravished Armenia.’”69 Unexpected findings have shaken silent movie buffs in the last years, such as Mary Pickford’s earliest film found in the attic of a barn in New Hampshire (2006);70 a complete copy of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis discovered in the Museo del Cine of Buenos Aires, along with three American and one Soviet silent movie (2008),71 and 75 American silent movies hailing from New Zealand (2009).72 It is not too bizarre to think that the elusive, complete version of “Ravished Armenia”—perhaps with a changed name—could be collecting dust in some forgotten corner of the continental United States, in Wellington, in Buenos Aires, or in some other place in this wide, yet small world. Time lends credence to this view and wings to hope.

Sources

1 Anthony Slide (ed.), Ravished Armenia and the Story of Aurora Mardiganian, Lanham (Md.) and London: Scarecrow Press, 1997, p. 17.

2 Special Report of the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures, January 25, 1919 (see the photograph in http://www.genocide-museum.am/eng/online_exhibition_6.php).

3 Mark A. Kalustian, “Ravished Armenia: The Auction of Souls,” The Armenian Mirror-Spectator, Nov. 7, 1987 (see idem, Did You Know That…?: A Collection of Armenian Sketches, Arlington (Mass.): Armenian Culture Foundation, 2004, pp. 140-145).

4 Aurora Mardiganian, Subasta de almas, Buenos Aires: Akian Gráfica Editora, 1999. For the text of the unpublished introduction, see Eduardo Kozanlian, “A propósito del libro ‘Subasta de almas’,” Armenia, May 19, 1999. There are also translations into Western (idem, ‘“Hogineru achurd’ girki masin,” translated by Vartan Matiossian, Haratch, June 24, 1999) and Eastern Armenian (idem, ‘“Hogineri achurd’ grki artiv,” Yerkir, Aug. 19, 2000).

5 Slide, Ravished Armenia and the Story, p. 17.

6 Goldberg had written to Kozanlian on Sept. 14, 1999: “I am writing, per our conversation, in search of permission to use your clip of the film Ravished Armenia starring Aurora Mardiganian. We would like to use your clip in our documentary on Armenian-Americans. (…) We will provide credit to you and any organization you are affiliated with at the end of our program” (Eduardo Kozanlian’s personal files, Buenos Aires).

7 See https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL652B7F8867E55844

8 Aurora Mardiganian, Subasta de almas, Buenos Aires: Arvest Ediciones, 2011. Contents: Aurora Mardiganian, “Subasta de almas”; Artsvi Bakhchinian, “El Genocidio Armenio en el cine,” translated by Vartan Matiossian; Sergio Kniasian, “Un investigador de Argentina descubre el film.”

9 See also Eugene L. Taylor and Abraham D. Krikorian, ‘“Ravished Armenia: Revisited:’ Some Additions to ‘A Brief Assessment of the Ravished Armenia Marquee Poster’,” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies, 2, 2010, p. 187. I would like to thank Eduardo Kozanlian, Marc Mamigonian, Artsvi Bakhchinyan, and Sergio Kniasian for providing information and sources for the writing of this article.

10 Artsvi Bakhchinyan, Hayere hamashkharhayin kinoyum (Armenians in World Cinema), Yerevan: Publishing House of Museum of Literature and Art, 2003, p. 47. The article mentioned in footnote 8 is a Spanish translation of pages 41-50 of this book.

11 ‘“Ravished Armenia’ in Film,” The New York Times, Feb. 15, 1919.

12 Motion Picture News, July 5, 1919.

13 “Hay gaghtakanutiun” (Armenian Community), Gochnag Hayastani, July 7, 1919, p. 872.

14 For the sake of example, in October 1919 Armin T. Wegner gave lectures in Berlin illustrated with slides of his photographs of the genocide (Sybil Milton, “Armin T. Wegner: Polemicist for Armenian and Jewish Human Rights,” Armenian Review, Winter 1989, p. 24).

15 It refers to the fact that the memoir was serialized in New York American, a morning newspaper published by William Randolph Hearst between 1895 and 1937. In this last year, it merged with his evening newspaper New York Evening Journal to become the New York Journal-American (1937-1966).

16 Vahan Chukasezian, ‘“Ravished Armenia’n” (“Ravished Armenia”), Yeritasard Hayastan, May 14, 1919.

17 Anthony Slide, Early American Cinema, new and revised edition, Lanham (Md.) and London: Scarecrow Press, 1994, p. 214. Mardiganian also appeared in J. Michael Hagopian’s The Armenian Case (1975) and was interviewed as part of the Oral History Project of the Zoryan Institute in the 1980s.

18 Moosheg Vaygouney, class of 1904 of the University of California, lived in Berkeley (“Directory of Older Alumni,” The Journal of Agriculture of the University of California, April 1917, p. 269).

19 Teghekagir Hay Azgayin Miutian Amerikayi 1917-1921 (Report of the Armenian National Union of America 1917-1921) (Boston: Azg-Pahak, 1922), p. 40.

20 Karekin Boyajian, “Der ke shahagortzvi hay pative” (The Armenian Honor is Still Being Exploited), Hairenik, April 26, 1921, quoted in Bakhchinyan, Hayere, p. 49.

21 See Artsvi Bakhchinyan, Armenian Cinema-100: The Early History of Armenian Cinema (1895 to mid-1920s), translated by Vartan Matiossian and Susanna Mkrtchyan, Yerevan: Armenian National Film Academy and Filmmakers’ Union of Armenia, 2012, pp. 143-146.

22 Shushan Avagyan, “Becoming Aurora: Translating the Story of Arshaluys Mardiganian,” Dissidences, vol. 4, iss. 8, article 13 (available at http://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/dissidences/vol4/iss8/13).

23 Slide, Ravished Armenia and the Story, p. 3.

24 The copyright was entered on Dec. 28, 1918 (Catalog of Copyright Entries for the Year 1919, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1919, p. 21).

25 H. L. Gates (editor), Hogineru achurde. Metz Yeghernen veraprogh hayuhi Orora Martikaniani vaverakan patmutiune (Auction of Souls: The Authentic Story of Aurora Mardiganian, an Armenian Woman Survivor of the Medz Yeghern), translated by Mardiros Koushakjian, Beirut: Zartonk Daily, 1965 (previously serialized in the daily Zartonk); Hoshotvatz Hayastan. Ays patmutiune Metz Yeghernits hrashkov prkvatz mi hay aghchka masin e (Ravished Armenia: This Story is about an Armenian Girl Miraculously Saved from the Medz Yeghern), translated by Gurgen Sargsyan, Los Angeles: n. p., 1995. It is noteworthy that both modern translations use the expression Medz Yeghern to translate the “Great Massacres” of the original (“The Christian Girl Who Lived Through the Great Massacres”/ “The Christian Girl Who Survived the Great Massacres”).

26 Armenia arrasada. Subasta de almas. El relato de Aurora Mardiganian, la joven cristiana, superviviente de las terribles matanzas, translated by J. R. López Sena, New York: International Copyright Bureau, 1919.

27 Atrocidades en Armenia. El exterminio de una nación, Edinburgh, London, and New York: Thomas Melson and Sons, n. d. For the date 1916, see Jean Pierre Alem, Armenia, translated by Narciso Binayan, Buenos Aires: Eudeba, 1963, p. 118.

28 Fa’iz-el-Ghusein, Armenia sacrificada, London: Oxford University Press, 1918. On this unknown Spanish translation (a microfilm of the book is available at the New York Public Library), see Vartan Matiossian, ‘“Armenia sacrificada’, de Fa’iz el-Ghusein. Un testimonio árabe y su desconocida traducción castellana,” in Nélida Boulgourdjian-Toufeksian, Juan Carlos Toufeksian and Carlos Alemian (eds.), Genocidios del siglo XX y formas de la negación. Actas del III Encuentro sobre Genocidio, Buenos Aires: Centro Armenio, 2002, pp. 277-291.

29 See http://www.genocide-museum.am/eng/online_exhibition_6.php

29 La Nación, Aug. 29, 1920.

31 La Razón, Aug. 31, 1920.

32 “Los principales estrenos locales,” La Nación, Aug. 29, 1920.

33 See the minutes of the Buenos Aires chapter of the Armenian General Benevolent Union, July 21 to Sept. 29, 1926 (in Armenian).

34 Baltasar de Laón, “Las familias armenias evadidas de Constantinopla al entrar en ella las tropas de Kemal bajá llegan a nuestro país,” Caras y Caretas, Feb. 10, 1923, where a photograph illustrated the game.

35 Bakhchinyan, Armenian Cinema-100, pp. 100-101. As a reflect of the Armenian tragedy, The Despoiler was preceded by two Russian feature movies, Bloody Orient (A. Arkadov, released in February 1915) and Under the Kurdish Yoke (a.k.a. The Tragedy of Turkish Armenia, A. I. Minervin, released in October 1915), of which there is no extant copy (idem, Hayere, p. 42).

36 Brian Taves, Thomas Ince: Hollywood’s Independent Pioneer, Lexington (KY): The University Press of Kentucky, 2012, p. 100.

37 See http://www.cinematheque.fr/sites-documentaires/triangle/impression/archives-photos-et-films-les-films-triangle-la-restauration-de-the-despoiler.php

38 Ian Scott, ‘“Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood’: British Filmmakers in Early American Cinema,” European Journal of American Studies [Online], Special issue 2010, document 5, par. 16.

39 http://www.afi.com/members/catalog/DetailView.aspx?s=1&Movie=13928

40 Henri Diamant-Berger, “Les films à voir,” La Rampe, May 17, 1917.

4[1] “Une date dans l’histoire du cinéma: La production Triangle 1915 1916 1917,” Ciné pour tous, June 3, 1921, pp. 8-10.

42 See http://www.cinematheque.fr/catalogues/restaurations-tirages/film.php?id=111751

43 Marc Vernet, “Vite, mettre en scène un génocide : The Despoiler, Reginald Barker 1915,” Ecrire l’histoire, no. 12, Fall 2013, p. 74 (see http://cinemarchives.hypotheses.org/1533).

44 Gevork Mirzoyan, “A Spirit of Perennial Youth,” Kroonk, 10, 1988, p. 21.

45 “Les présentations prochaines,” Les spectacles, May 11, 1928, p. 12; “Les présentations prochaines,” Les spectacles, May 18, 1928, p. 13.

46 See the advertisement in Cinémagazine, Sept. 10, 1926.

47 “Un choix heureuse,” Les spectacles, Sept. 2, 1927, p. 5.

48 Kinematograph Year Book, London: Kinematograph Publications Ltd., 1931, p. 27.

49 “Les présentations,” Les spectacles, May 25, 1928, p. 2.

50 “Haykakan taragrutiants filme” (The Film of the Armenian Deportations), Aztag, Jan. 19, 1929.

51 Abaka, Feb. 23, 1929, quoted in Bakhchinyan, Hayere, p. 48.

52 Bakhchinyan, Hayere, p. 312.

53 Mirzoyan, “A Spirit,” p. 22.

54 Gevorg Mirzoyan, “Vogin chi tzeranum” (The Spirit Does Not Grow Old), Sovetakan Hayastan monthly, 10, 1988, p. 34. The identity of “Reverend Father Rupen” remains undisclosed.

55 Mirzoyan, “A Spirit,” p. 23.

56 Vladimir Badasyan, “Der Zor (1926 t.)” (Der Zor, 1926), Kino, 8, 1991.

57 Mirzoyan, “A Spirit,” p. 23.

58 Badasyan, “Der Zor.”

59 Bakhchinyan, Hayeri, p. 48.

60 “British Drop Film Ban,” The New York Times, Jan. 21, 1920.

61 Slide (ed.), Ravished Armenia and the Story, p. 6.

62 Matilde Sánchez, “Imágenes mudas de Armenia,” Clarín, April 21, 1996. See Eduardo Kozanlian, “Los ojos de Cine Seto,” Armenia, Oct. 14, 1998 for a biographical outline of Setian and a personal memoir.

63 Artsvi Bakhchinyan, “Hartsazruyts Eduardo Gozanliani het” (Interview with Eduardo Kozanlian), Yeter, Nov. 17, 1999.

64 Sánchez, “Imágenes mudas.” For a brief reference to the discovery of the film, see Narciso Binayan Carmona, Entre el pasado y el futuro: los armenios en la Argentina, Buenos Aires: n. p., 1997, p. 284.

65 See Barbara J. Merguerian, ‘“Ravished Armenia’ Revisited,” The Armenian Mirror-Spectator, June 1, 1996 (Armenian translation: idem, “Ravished Armenia,” Nor Gyank, July 18, 1996).

66 For a picture of the jacket and a short discussion of the VHS and the DVD, see Taylor and Krikorian, ‘“Ravished Armenia: Revisited,” pp. 187-189, to whom we owe the identification of the music’s author. It is unclear whether the DVD used the VHS or one of Kozanlian’s copies as raw material.

67 See also the online exhibition about Ravished Armenia by the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute of Armenia, uploaded in 2009, which acknowledges Kozanlian’s role (http://www.genocide-museum.am/eng/online_exhibition_6.php).

68 Nick Allen, “Thousands of silent Hollywood films ‘lost forever,’ The Telegraph, December 5, 2013.

69 Slide, Ravished Armenia, p. 17.

70 Holly Ramer, “Mary Pickford Film ‘Their First Understanding’ Found in Barn Is Restored,” Huffington Post, Sept. 24, 2013,

71 Larry Rohter, “Footage Restored to Fritz Lang’s ‘Metropolis,’” The New York Times, May 5, 2010.

72 Dave Kehr, “Long-Lost Silent Films Return to America,” The New York Times, June 7, 2010.

The post The Quest for Aurora: On ‘Ravished Armenia’ and its Surviving Fragment appeared first on Armenian Weekly.