This article is the second in a two part series written by Armenian Weekly columnist Lalai Manjikian. To read part I, click here.

Every fall, my father who was born in Kessab, plants tulip bulbs in his Montreal garden, miles away from his ancestral land. I like to think he does so in an unspoken homage to Kessab—every year, renewing his unbreakable connection to his past.

As a child, my first memory of seeing red wild tulips grow in their element were on the raw mountains of Kessab, as opposed to being neatly transposed in a living room vase. It was a significant sight, given the fact that my parents had named me Lalai, which is this flower’s literary name. Surrounded by wild tulips and towering mountains, I too felt in my element, feeling a strong relationship with this mesmerizingly powerful land where my roots originate.

Only a few weeks ago, I browsed through pictures of Kessab in bloom posted on Facebook. I saw the hopeful images of trees beginning to blossom, warm Kessabi hatz (bread) straight out of the toneer (stone oven). Village life seemed to unfold as usual. I caught myself quietly smiling at pictures of children in Kessab dressed up for Paregentan in colorful costumes, with their radiating smiles seemingly untainted from severe civil unrest engulfing the region for the past three years. These photos provided me with a fragile sense of comfort that all is fine on the Kessab front, even as I thought of the current situation in Syria, where Kessab is precariously nestled in the country’s northwest corner, on the Mediterranean Sea, bordering Turkey.

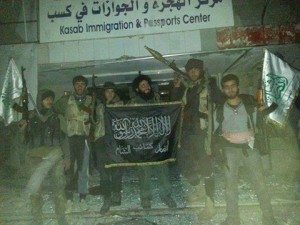

A few days ago, like a flash flood, those images of a Kessab spring were violently shattered. Years of hard labour, sweat, and love left behind following an attack on this treasured part of Armenian history dating back to the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia. The predominantly Armenian enclave of Kessab is now emptied of its Armenian population that has been there for hundreds of years, after rebel forces descended on the region from Turkey.

Houses are being looted, Armenians being displaced. We all know too well this recurring refrain etched in our collective memory, as history coldly repeats itself.

Over the past few days, anyone who has spent some time under Kessab’s magical spell or any Armenian for that matter has been taking numerous stabs in their hearts. Memories flooding our minds, as news trickles out from the region, and as the international community just watches with a blank stare, once again.

Perhaps naively, I always wanted to think that Kessab was untouchable, that it was my only tangible connection to my already devastated family tree, to my past, to my ancestors, at least on my father’s side. My mother’s family from the region of Tomarza in the Kayseri province still stand, but it is was long lost in many ways. Kessab, on the other hand, has always been alive for me. Accessible, it is living, breathing Armenian life, where old and new generations solidly overlap, like interlocking elbows during countless “Garmir fustan” dances endlessly streaming at weddings, baptisms or massarah/perpoor nights (grape molasses cooking feasts). A land where tradition is celebrated, a comforting dialect is spoken, where characters are as unshakable as the rocks that make Kessab. It is a place that is constantly renewed with the incessant flow of Kessabtzis coming and going to and from this enclave, bringing in the new, but also replenishing themselves with the water, air, food, and unfailing hospitality and genuineness of this rural marvel, still standing tall and strong like its mountains in the lap of the Mediterranean Sea.

We all know too well this recurring refrain etched in our collective memory, as history coldly repeats itself.

Countless lives started on that land. Men and women who perhaps moved on to other parts of the world, where they exceled in various domains, but always carried Kessab close to their hearts, and most importantly, always returned.

It is the only place where generations of my forefathers and mothers graves are marked, where life came full circle on a land they worked hard to maintain and where they now rest. A real gift that no one can afford to lose for a people afflicted with genocide where burials are scarce.

However days of victimhood are long gone. Resilience and survivorhood are practically engraved in our genetic make-up, with Kessabtzis being a special breed amongst Armenians, where will power, perseverance, and determination are defining common traits.

Spring has arrived in Kessab and as long as the wild tulips will pop their vivid red heads out, all the inhabitants of Kessab will eventually return to their homes and lands. All of us in the diaspora who are connected to Kessab in one way or another will visit again.

Who can give up on what they have loved, nurtured, protected for so long? Kessabtzis certainly never will.