Special to the Armenian Weekly

In 2005, a Turkish workman named Murat finds a dusty postcard hidden behind the wooden panels of a wall in an old house in south-central Turkey, in the city of Antep (Gaziantep).

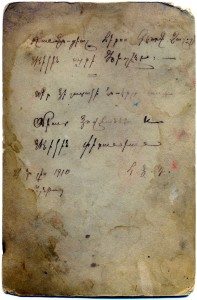

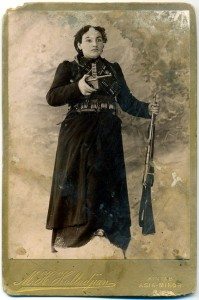

Image of the postcard found in the wall of an Armenian home in Ayntap: Heghine, the widow of Kevork Chavoush, with Mauser handgun in her right hand and a shortened-barrel (or stage prop) Mosin rifle in her left

On the front of the postcard is the black-and-white image of a woman in a long black dress; she’s holding a handgun in her right hand and a rifle in her left. Bandoliers are wrapped across her chest and around her waist. Nearly lost among the bullets and leather is a round brooch or medallion above her left breast.

In English, at bottom-left, is an embossed signature, “M. H. Halladjian,” and at bottom-right is a place name, “Aintab Asia-Minor.” On the back of the postcard is handwriting in a language that’s alien to Murat; only a part of a date is comprehensible: 1910.

* * *

Halfway through the first week of a draining two-week “pilgrimage” through historic Armenia, on May 26, 2013, our group of 12 Armenian “pilgrims” arrives in Antep (Ayntap, or Aintab, in Armenian). Our guide, Armen Aroyan, explains that the city was renamed Gaziantep—”Heroic Antep”—for having repulsed British and French armed forces in 1921, during the war of “liberation” that resulted in the founding of the Republic of Turkey in 1923.

As we drive through the city, it seems vaguely familiar, though I’ve never been here before. I can see parts of Beirut and Aleppo in both the old and the new buildings, the dusty cobblestoned streets, the small shops lining them.

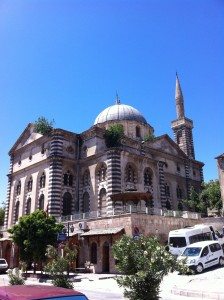

Our van pulls up to an imposing structure overlooking a main street. It’s the Sourp Asdvadzadzin (“Holy Mother of God”) Church, built in 1892, now converted to a mosque and renamed Kurtuluş Camii (“Liberation” mosque), Armen explains. After the long drive from Musa Dagh in our brand new Mercedes passenger van, we gladly begin to exit. My son, Garin Shant, my youngest, bounds out like a falcon fleeing a gilded cage; others, including my father, move out wearily, stretching old muscles that have grown accustomed to the inertia of sitting and waiting. All of us gradually make our way up, toward the church-mosque.

Using a magnifying glass, one is able to almost fully make out Heghine’s medallion/brooch, of a coat of arms consisting of a banner, on top of which are assembled a sword, feather pen, and spade, and three Armenian initials below them: Հ Յ Դ. (A.R.F.)

The wooden doors on the side of the building, facing us, are locked. The members of the group move on in various directions around the building, taking pictures. I walk to the “front” of the church-mosque, toward a wide walkway/courtyard overlooking the street; I’m actually at the back of the church, behind the altar, I find out later. Leaning against the railing I look over the edge. Across the street, I can see half-standing ruins of large houses with red clay roof tiles, and I notice a small, cross-shaped opening or window—then another. Considering their proximity to the church, and their grand size, they must be formerly Armenian-owned homes, I think to myself. I take pictures of them with my iPhone, knowing full well that I am too far to be able to capture the images of the windows.

I hear, then see, a small old man off to the side, behind me, sweeping the ground. His faded, oft-torn and oft-mended clothes hang loosely on his small frame; his shoes, too, are worn. For a split second I think he’s wearing a shalvar and pabuches.

He sweeps seemingly in slow motion, in half-hearted, incomplete strokes; just as likely, he’s simply too old, his range of motion limited, his limbs atrophied and no longer limber. I greet him with my nearly nonexistent Turkish and try to ask whether the mosque is open.

He motions that I follow… He’s dealt with tourists before. I follow. His pace is maddeningly slow. He doesn’t walk. He shuffles. Haltingly. I slow my pace to match his; he has the key, after all. And I don’t want to be rude, to imply with eager steps that he should walk more quickly. But I’m restless—have been for the entire trip so far—as if wanting to quickly reach the next place, then the next and the next, but also wanting to stay, absorb the essence of each site, to feel a part of it. Yet I can do neither.

Eventually, the old man reaches the wooden doors, in the meantime having built a small following of pilgrims curious to see what lies within the church-mosque. The doors creak and slowly swing open. The old man steps in, takes off his dusty shoes, and places them on a rack. We follow him in and take off our shoes, too.

We make our way around a partition to enter the church-mosque proper and are immediately confronted by the overwhelming red of an overly large Turkish flag dominating the wall in front of us, the only thing of color in relatively stark surroundings, though the interior of the church is beautiful. The oriental carpet beneath our stockinged feet makes the space seem tolerable, hospitable.

I immediately begin to walk along the walls, looking up and down for a remnant of anything Armenian, as I’ve done throughout the trip. (And, if I’m to be honest, as I’ve done all my life, pretty much everywhere I go. I suppose that’s what happens when one’s sense of home feels fragile and hazy.)

I find nothing on the cold walls of the church-mosque. Until I look up, high above what used to be the altar, above yet another large Turkish flag, and notice a medallion-shaped…something. The abandoned altar is too dark, and I can’t tell what the shape contains because what had once been there has eroded with time, or it has been intentionally chipped away. It’s even possible that it had contained nothing in particular, I think, then quickly dismiss it.

I take a few pictures, again knowing that I likely wouldn’t be able to capture a clear-enough image of what had once been there. Only after I place the iPhone in my pocket does the thought occur to me: Many Armenian churches have the figure of a dove or the letter “Է” above the altar—signifying, respectively, the Holy Spirit and God. Whichever had been there, the presence of neither seems very apparent now in the church-mosque.

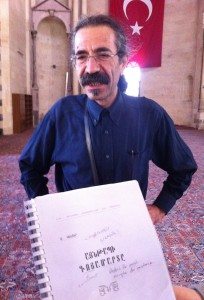

Murad, who discovered the postcard of Kevork Chavoush’s widow and subsequently translated Ayntapi Goyamarde from Armenian to Turkish

Normally, I wouldn’t feel great affinity toward a religious symbol—Christian, Armenian, or otherwise. But in its current, altered state, that empty medallion shape elicits…what? Resentment? Loss? Anger? Frustration? Sorrow? Those and much more that I cannot name, or probably even comprehend.

No wonder ancient (and not so ancient) cultures have assigned and ascribed so much power to symbols, amulets, and other talismanic objects, believing they hold power in, and influence over, the physical world.

They affect thought. And so they effect change.

In this case, it is the absence of an object—rather, the existence of a mere hint of it—that casts a powerful presence, substantiating what I sense and feel and know: that this building is not now what it once was, that what it is now isn’t really what it is, or is made to seem to be.

Every molecule of every remaining inanimate object of Historic Armenia is a microcosm of immense loss, massive erasure, and a brutal re-rendering of reality.

* * *

A stranger has joined us in the church-mosque. Armen introduces a few of us to an Antep native, Murad, a tall, thin, mustachioed Turk with dark hair tied back into a ponytail. He seems at once laid back and intense—the type who subsists on coffee and cigarettes. Apparently he and Armen are old friends. They do some catching up, discussing pictures of old Armenian homes that Murad has recently emailed to Armen.

At some point, standing in the middle of the church-mosque, Murad takes out some papers from his bag. A few of us gather around as he explains, in English, about a project he’s been working on. The papers are photocopied pages of an Armenian book, Ayntapi Goyamarde (“Ayntap’s Battle for Survival”) about the Armenian battles of self-defense against Turkish attacks in 1920-21. The author is A. Kesar, and the book was published in 1945, in Boston, by the Hairenik Press. I was once an editor at the Hairenik, I point out, surprised, never imagining that I would come across anything in the middle of Ayntap that would remind me of my long years in the Hairenik building in Watertown, Mass.

The cover page has notes in Turkish and English scribbled over and around the title. Murad flips through some pages, and we see how nearly every millimeter of white space between the lines of printed Armenian text contains handwritten Turkish. Murad explains that he has taught himself the Armenian alphabet, and with the help of dictionaries he’s been translating the Armenian text into Turkish so that he may learn the untaught history of his hometown.

I’m incredulous: Really? Why? How? A Turk learning Armenian so that he could translate the Armenian view of events in his “heroic” hometown nearly a century earlier?

The setting—an Armenian church seized and converted into a Turkish mosque and ironically renamed “liberation”—makes the proposition seem even more surreal: A Turk who is, in essence, “converting” Armenian text into Turkish. But now the intent is to reveal, not obscure, to reclaim, to name things as they are. To liberate.

Murad, an electrical engineer by training, tells us some of the back-story. The following is the version he emailed to me a couple of months after we’d met:

“Once upon a time I was a house restorer. At that time, I did not have sufficient information about the original (Armenian) owner of the buildings. I’d only have information on the owners after 1923, when the Turkish Republic was declared. During the restoration of an old house in the Kayajik region [of Antep], we had to restore some wooden parts of the house. The house had seven rooms and a big living room. I started to work in a small room on the first floor of the house. The architectural style of that room was that all of the walls were covered with wood, but unfortunately most of the wood was destroyed by the effect of humidity. For this reason, we decided to renovate all the wooden parts of this room. But we had to be careful when removing the old wood because the limestone under the wood could be damaged.

“When I started the removing operation, I found a picture between the limestone of the wall and the wooden part. First, I thought it was an ordinary paper, but when I looked it carefully I noticed that it is a photograph covered by dust. When I cleaned the dust, I saw a young woman with arms [weapons] and I could read, ‘Aintab Asia-Minor’ and ‘M.H. Halladjian.’ I thought most probably M.H.H. was a photographer and this is a very old photo. When I looked the back side, I could read only ‘21…1910.’

“As you can guess, I could not read the other parts of the writing. I thought the writing is in the Arabic language because at that time Ottomans used Arabic letters for writing. When I asked a friend who knows Arabic, he said, ‘This writing is not Arabic, it could be the Armenian language.’ Later, I met a family [of Armenians] who visited Antep, and they translated the writing.

Transliteration (in Western Armenian)

Hankoutsial heros Kevork Chavoushi

Digin ayri Heghine.

=

Mer hishadagi nvere asd[?]

Diar Hovhannes yev

Digin Piranian

21 Houlis 1910 H.H.T.

Aintab

The English translation

Deceased hero Kevork Chavoush’s

Wife, the widow Heghine.

=

Our memento this/here[?]

Mr. Hovhannes and

Mrs. Piranian

21 July 1910 A.R.F.

Ayntap

“Before the translation, I had one question: ‘Who was M.H. Halladjian?’ But after the translation, I had more than five questions. ‘Who were these women and men?’ Then, I decided to search for the history of Antep. These [events] happened in 2005.

“Later, I met with Armen Aroyan, and he gave a Xerox copy of the book K. Sarafian’s Brief History of Aintab. After reading that book, I decided to learn the Armenian language, because the history of Antep can not be researched and understood without the Armenian language. Now I can read, and with the help of a dictionary I can understand Armenian.”

* * *

The Murat of 2005 had become the Murad we met in 2013 at the Sourp Asdvadzadzin Church/Liberation mosque of Ayntap/Aintab, Antep/Gaziantep. At some point, I find out later from a mutual friend, he had changed the spelling of his name.

I’m not certain why. But I know it has something to do with people, places, and things.