By Varak Ketsemanian and Raffy Ardhaldjian

Special to the Armenian Weekly

May 28 just passed and Armenians celebrated Republic Day—the holiday that commemorates the day when Armenia became a republic and a reference to the first modern Armenian state of 1918 since the loss of Armenian statehood in 1375.

Clik here to view.

A demonstrations in Yerevan in the late 1980s (Photo: Ruben Mangasaryan)

This year marked the 99 years of independence for Armenia. While it is a small blip in our long history, it is an important milestone to critically reflect on. It was an attempt at establishing both a physical Armenian statehood and the best government possible at the time.

Since then, also in 2017, Armenia just passed through historic Parliamentary Elections that transitioned the country into a parliamentary democracy enshrined by Armenia’s new constitution. While the elections were at times tainted by instances of vote-buying and interference, technical solutions and procedures to address voting irregularities and fraud seemed to have improved election standards as Armenia limps in its post-Soviet transition. While most diasporan communities were busy campaigning for the movie The Promise, an unprecedented conference took place in Yerevan in April, addressing a political vision that has recently gained momentum in Armenia’s political parlance—namely “Azg-Banak” (A Nation in Arms/Das Volk In Waffen).

Against this backdrop, there seems to be misdirected anger, much confusion, and some apathy within the nation globally as it transitions into its next century of post-genocide collective future and faces the challenges of stable and sustainable statehood.

In this article, the authors aim to address some key questions for Armenian political thought in the 21st century. What does May 28th evoke in Armenians 26 years after Armenia became an independent country? Is it the century old Turkish-Azeri existential threat as demonstrated in populist nationalism that underlies modern Armenian identity? Is Armenia a failed state? Or does it trigger even deeper issues like Armenia’s transitional struggles from “post-Soviet” to being an “Armenian state” as Armenians face the challenges of statehood?

Both authors matriculated in the Lebanese-Armenian community, where May 28th was always a favorite holiday, as it evoked a sense of hope and rebirth. At the Hamazkayin Palandjian Djemaran Lyceum of Beirut (where both authors went to school), generations of Armenian public intellectuals were educated, including Dr. Vartan Grigorian (President of the Carnegie Foundation). Statues of previous principals Levon Shant (Vice Chairperson of the Parliament of the First Republic) and Simon Vratsian (the last Prime Minister of the First Republic of Armenia) were constant reminders of hope for diasporan generations. Intellectual discourse in this “exilic nationalist” context[1] often addressed “Armenian values” as youth interacted with leaders of the First Republic like Garo Sasouni and others.

Clik here to view.

A 1994 Armenian postage stamp dedicated to the 125th Anniversary of the birth of Levon Shant (1869-1951)—Vice Chairperson of the Parliament of the First Republic

The sense of hope that the founding fathers of the republic were able to achieve stands in contrast in many ways to today’s reality. The future of Armenian attempts at statehood is frankly unclear to many in the diaspora. The Armenian pursuit of nationhood and statehood seems to have followed a thorny path since the 1860s—a path that included genocide, Sovietization, Bolshevik terror in the 1930s, huge losses in World War II, and recently blockade and war with Azerbaijan.

But things worsened for the Armenian republic since 1991, as one third of Armenian’s population left the homeland, mostly as a result of the de-industrialization of the national economy and increasing unemployment rates. In the various communities of the diaspora, on the other hand, Armenian identity seems to be facing assimilation, and some drift into once familiar ethno-religious identities and communities. A phenomenon, nowadays much accelerated by technology and globalization, turning communities into various local sub-cultures, and away from the Armenian “collective agency” of the post-genocide generation.

It seems that humanity and globalizations are providing more communion to Armenians than the nascent nation state itself and global Armenians seem to be drifting towards local ethnic commitments rather than genuinely multi-local diasporic engagements[2]. Ethnics differ from diasporics in the fact that their perspectives are not “multilocal” and do not link their local identity with their imagined relationships with other Armenians elsewhere as well as the homeland. Armenians also seem to be moving passively into the realm of “individual agency” as more are able to work globally in more places. But is humanity too large and too diverse to provide meaningful communion to the members of the small Armenian nation? Are local ethno-religious communities enough to counter transnational liberalism & multicultural pressures? Are “paper Armenians” without any political attachment (inside and outside Armenia) enough to further develop a nation state after 100 years of statehood? While it is hard to envision a perfect society, we feel it is appropriate to bring up key questions on Armenian society in the aftermath of Republic Day.

Ideologically speaking, looking at Armenian nationalism of the last quarter century, we feel that by itself, it has mostly been insufficient to create the key objectives of an ideology for a nation-state. Mainly, Armenian nationalism has been unable to:

- Create a sustainable national economy;

- Create proper governance that integrates communities and regions of Armenia outside of Yerevan and the diaspora(s);

- Create a minimal national political culture (a system of common values and Armenian worldviews) and identification for the entire nation, including the diaspora(s);

- More fundamentally, we feel it failed at creating efficient governance that responds to citizen needs. One that learns from others in devising policies and uses data and scenarios in its long term planning and execution.

In a larger context, while the language of the Armenian “transnation”[3] and now the “Global Armenian” (by the likes of Ruben Vardanian among others ) is employed to describe or evoke new identities, in fact there seems to be no substantive collective, national identity that can be the source of mobilization and “collective agency” in the face of crises or a national vision.

We feel that the only real rallying cry came in April 2016 during the four day April War as worldwide Armenians felt a familiar existential threat for a brief period. The globalization of Armenians today might require reconstructing new principles to motivate the nation’s “best and brightest “within and outside the homeland. It might require multifocal identities linking them to their locality and the homeland, combining transboundary, cross-border culture, politics and democracy, and encompassing a larger segment of Armenians than the ever shrinking two million citizens of Armenian (35% of whom seem to be trapped in post-soviet poverty) or any tiny ethno-religious community of the diasporan sub-cultures.

The authors believe that an alternative to the existing ideological void could be the gradual development of civic forms of Armenian constitutional patriotism as a value system within the nation state and its diasporas. What does patriotism mean? According to Ron Paul (a U.S. populist ideologue). “A patriot is an individual who is also willing to stand up against one’s own government if need be when the government is wrong.” In the case of Armenian identity, the attachment to the homeland will need not only be triggered when external threats exist, but also guided with deep common social values that can provide a more cohesive platform for effective and inclusive work. We call it the “Armenian value stack.”

We argue here that Armenian political thought in general should recast itself as a defender to an “Armenian values stack” in the fast changing realities of the 21st century. Political scientist Irina Ghaplanyan would call this “meaning creation”[4] which could also signify articulating what the new processes and institutions of nation building development would entail beyond a normative understanding. If the Armenian modern nation is going to revive past its post-Soviet identity as the primary political vehicle to sustain the trans-nation going forward and differentiate it from the alternatives of migration, then at a minimum better definitions of “meaningful Armenian values and a sense of destiny” need to be articulated by Armenian political thought.

In this context, we feel that these values should contain much more than what’s being omitted from modern Armenian nationalism; these values need to go beyond just ethnic traditions and ritualistic religious norms (yes, our church is ritualistic and not necessarily spiritual) and address relevant economic and social policies that impact Armenian citizens and diasporans the way other small nation states like the Nordic countries, Singapore, and even Dubai have done.

What has been omitted from populist liberal nationalist narrative today is Armenian society’s deep social, structural and institutional issues. These include the crackdown on civil society, Armenian women’s issues, and most importantly financial inequality and the cause of the poor.

The other aspect in today’s Armenia that troubles the authors is Armenia’s neo-liberal elite’s often-ferocious sense of entitlement (including the self-serving diasporan ones) that views Armenia as a personal canvas and experimentation zone. Increasingly, we are seeing “non-inclusive elitist and often exclusive tendencies” in all aspects of societal life ranging from education to culture and business. It is as if the elite has imposed its own cast system on society between the haves and have-nots. The haves feel entitled to control politics, business, country governance as well as the attempts at designing/institutionalizing how a future Armenia will look like and operate. And the rest are expected to serve in the Army, perform sideline cheers, act as the help/workers, or be miserably poor. The authors are less worried about relative differences in economic equality here, and more about fairness articulated through, institutional efficiency and opportunity.

The First Republic of 1918, ruled for a brief period by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) as a “center left party” at the time, was not the monopoly of a single party or societal class in the context of its times. It can be argued that it actually was a progressive bastion in many ways—it had the first ever woman ambassador in the history of modern diplomacy, Diana Abgar. We will not begin to comment on women’s rights in Armenia today, since much has come out in media recently. We feel we have collectively regressed.

Clik here to view.

Diana Abgar

Practically speaking, the authors believe that the next Armenian ideological war will not be fought on nationalistic battlefields or even in the hearts and minds of Armenians. It will be fought with cold, hard facts delivering answers to questions like if Armenia’s economy can deliver growth and if impoverished citizens have a chance to rise from poverty based on their merit. Citizens will look at how efficient the allocation of labor and capital in Armenia are, and if the rules of the game are stable enough to encourage growth and a better future for their offspring. Otherwise, they will emigrate. This is a reason for Armenian political minds to make essential services like the education system work better, and not leave it to chance. For instance, children born in the regions outside of Yerevan today will enter the workforce much less prepared than those of the elite in Yerevan.

The Declaration of State Sovereignty of Armenia (1990) which included 12 statements, and which later served as the “basis for the development” for the Armenian Constitution until today, does not seem to reflect the “Armenian value stack.” Outside of the nation state, we feel that most trans-state Armenian institutions, including the church and others, are not in sync with the times and failing to sustain the “feeling of communion” and common bonds between the nation as a whole and the homeland.

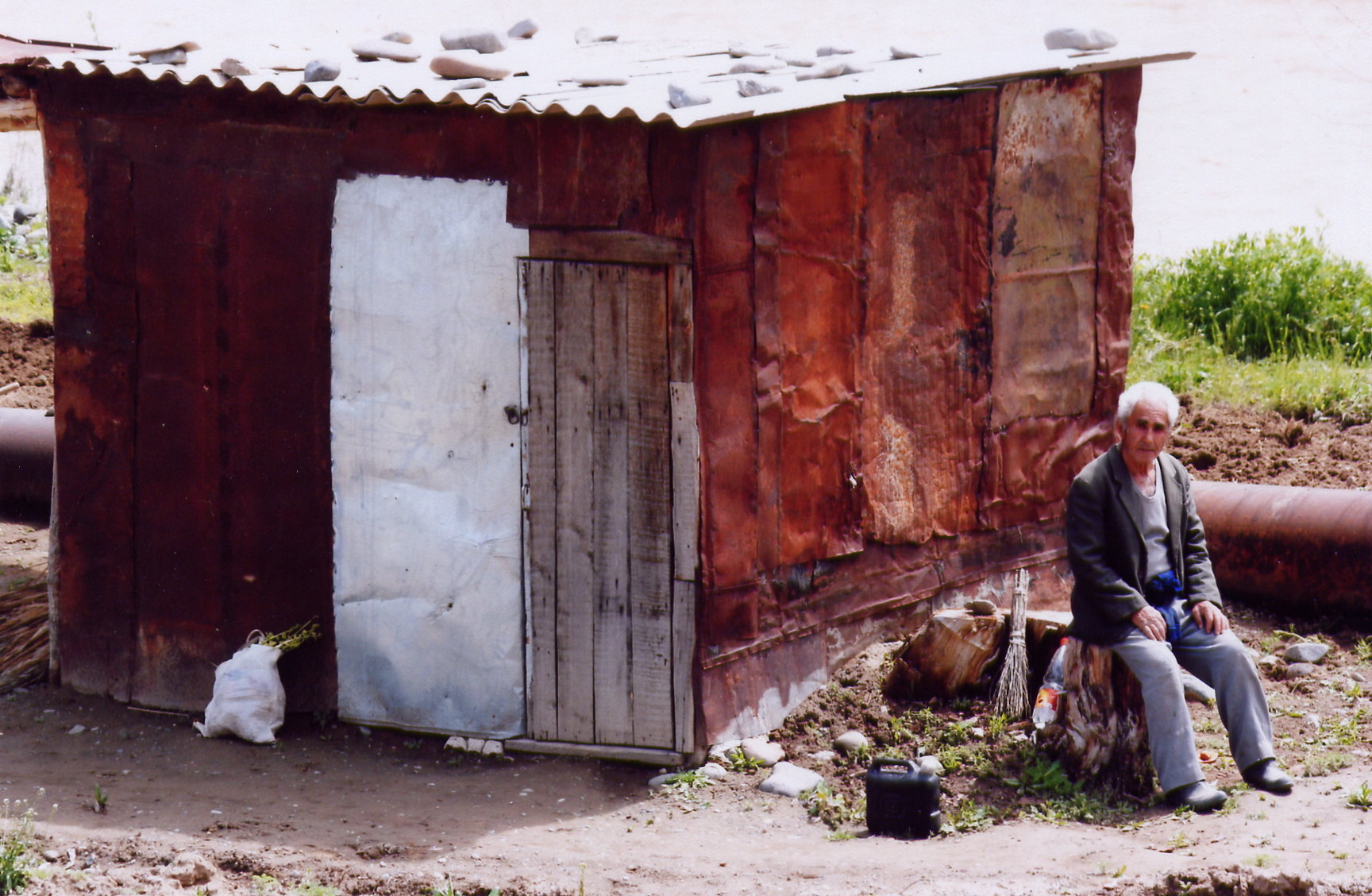

Clik here to view.

A man sits outside a lean-to he calls home outside of Yerevan. (Photo: Tom Vartabedian)

Clik here to view.

A girl holds her cat in an impoverished part of Dilijan (Photo: Raffy Ardh

In such an environment, narrow Armenian nationalist political ideology merely based on ethno-religious identities of a small nation that wants sovereignty and self-governance, is becoming increasingly ineffective in the complex dynamics of the 21st century. In the post-Cold War era, Armenians dreamed of a “new world order,” in which the spread of democracy and work ethic would automatically bring about a free, independent, and prosperous Armenia. That dream seems to be over, and a long road towards much needed development lies ahead if Armenians want to face up to the challenges of statehood.

In 2017, the Republic of Armenia officially shifted into a parliamentary democracy like most European countries. Yet the political spectrum (along the left–right axis) in Armenian life leaves much to be desired for and has room for further development. For instance, despite the presence of the ARF in the government, the party’s left wing ideology has hardly been felt in Armenia in the last 25 years. Calls for social justice by the ARF have not been backed by redistributive social and economic policy action. A recent a study commissioned by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung shows most Armenian youth are firmly on the socialist end of the spectrum.[5] Similarly, other key issues, such as feminist and green ideologies, have not yet found their proper place in the Armenian left–right political spectrum

While Armenians throughout the world get ready to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Republic next year, a lot remains to be done to be true to the spirit of the founding fathers of the 1918 Republic beyond the usual commemorative efforts and statue erecting ceremonies. Just like Aram Manoukian, who is widely regarded as the founder of the First Republic of Armenia, “forged an army from disheartened men,”[6] today’s challenges in Armenia require similar political will and resourceful minds.

Clik here to view.

The coat of arms of the First Republic of Armenia

We would like to end with a quote from a blog post of the late Allen Yekikian. “Years ago amid the chaos of the First World War and the turmoil of genocide, a small but resilient people drew on their legendary past for strength as they made their last stand for freedom at the gates of Sardarabad. At stake was their very survival.”[7]

Today almost a century later, at stake is the survival of the very Armenian state. This time its security is not only threatened by the Turkish-Azeri axis (and Russian geopolitics)—it is also threatened by the vacuum in Armenian political values and the lack of an Armenian worldview that connects Armenian identity with the state as we continue facing the challenges of statehood. Reversing these trends will require nothing less than a moral renaissance in Armenian life. Armenians need to develop a passion for righteous discontent with the status quo if a collective state is of any importance.

Two-hundred thousand years ago, humans originated in Africa and expanded through migration and evolution into the Armenian plateau and beyond. That evolution is still constantly at work as global migration and adaption figures show. The amount of information that comes into our brains today in one day exceeds what the average Armenian experienced throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. It seems that the path forward in statehood will require that Armenians refine a clear, differentiated positioning to give their nation state an advantage in attracting investment, business and tourism, and in building markets for its exports. Most importantly, it will require Armenians to further define the principles of “the Armenian dream” so that the Armenian identity provides “meaningful communion” in the context of a challenged nation state when many alternatives exist. For instance, the Nordic countries with a population of only 26 million provide a strong example of a collective “value stack” that has been evolving and adapting to modern life. Many that choose to live there do so partly because they like the “Scandinavian Dream.”

Liberal or populist nationalism cannot simply be the answer to Armenia’s statehood challenges. There is the urgent need to dig deeper in the midst of the intellectual crisis as Armenian ethno-national identity continues to adapt and evolve. “Mer Hayrenik,” the national anthem of the Republic of Armenia in 1918, was re-adopted as the anthem of the newly-independent state in 1991. Today, it is practically an element of civic education in Armenia and the diasporas. For it to provide meaningful communion to the Armenian trans-nation for generations to come, it will need to continue to evoke a deep sense of patriotism and devotion to not only a geography and an ancient culture, but increasingly to novel civic values of a modern and efficient Armenian society.

***

This is the first article in a series dedicated to the 100th Anniversary of Armenian statehood.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Varak Ketsemanian is a frequent contributor to Aztag Daily, Asbarez and Armenian Weekly. He is currently a PhD student at Department of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University

Varak Ketsemanian is a frequent contributor to Aztag Daily, Asbarez and Armenian Weekly. He is currently a PhD student at Department of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University

Raffy Ardhaldjian is a finance/technology professional and diasporan Armenian political thinker with an engaged history in social Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. entrepreneurship in Armenia since independence. He holds graduate degrees from the Fletcher School of law and diplomacy and the University Of Chicago Booth School Of Business.

entrepreneurship in Armenia since independence. He holds graduate degrees from the Fletcher School of law and diplomacy and the University Of Chicago Booth School Of Business.

Notes

[1] Tölölyan, Khachig. “From exilic nationalism to diasporic transnationalism”. The Call of the Homeland: Diaspora Nationalisms, Past and Present, co-edited by Allon Gal, Athena Leoussi, and Anthony Smith, Brill (The Netherlands, 2011).

[2] Tölölyan, Khachig. “Rethinking Diasporas,” Diaspora: a journal of transnational studies, Volume 5, Number 1. pp. 16-7.

[3] Tölölyan, Khachig. ”Elites and Institutions in the Armenian Transnation,” Diaspora: a journal of transnational studies, Volume 9, Number 1. pp. 1-16.

[4] Ghaplanyan, Irina. personal communication, (Feb 1, 2017).

[5] “Independence Generation Youth Study 2016 – Armenia”. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (Yerevan, 2016)

[6] Tsarukyan, Andranik. “Tught Ar Yerevan” (“Letter to Yerevan”) 6th ed. Hairenik (Boston, 1954). pp. 22-23.

[7] Excerpt from the blog May 28: At stake was the survival of a nation (May 28 2008)