Special for the Armenian Weekly

Hundreds of people in a well-lit room dotted with tables, and somehow I’m discovered amidst it all. I’m the shy, 14-year-old being approached by a short, stubby, eager man with graying hair and a face carved with wrinkles. He’s smiling.

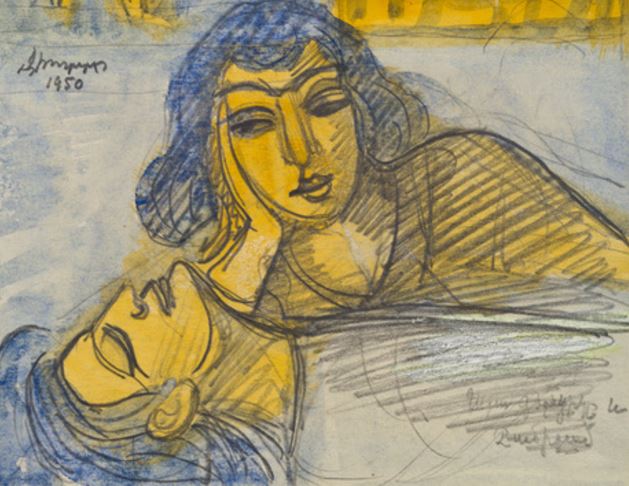

Ara and Shamiram, 1950 – paper, water color, pencil. By Gevorg Grigoryan (National Gallery of Armenia)

On second thought, it’s not all too surprising. I’m a blonde in a room full of Armenians.

“Are you Shamiram?”

He speaks English—a relief. I smile sweetly and nod. The man beams and thrusts out his arms—ta-da!

“I am Ara!” he says, “You know the legend, yes? We must have a picture!”

We pose and smile. I’m too timid to make conversation with him and he melts back into the crowd.

I’m at an event with my Auntie Pauline and Uncle Armen, celebrating the donation of an osteoporosis machine to an Armenian hospital by Auntie Pauline’s brother, John Bilezikian. The machine is the reason for our trip, as its donation is in honor of their late mother Zabelle Bilezikian. We make up a little posse of Bilezikians and Barooshians: John and his wife Sophie, their nephew Greg and his wife Nancy, Uncle Armen Barooshian, Auntie Pauline (a former Bilezikian) and me, Shamiram Barooshian.

There’s also Larry. His last name is Mowat. He’s here for work, representing the company that makes the osteoporosis machine. He’s not Armenian.

***

Roughly three thousand years ago, on the banks of the Tigris River near modern-day Baghdad, there lived a beautiful woman named Shamiram.

Shamiram was queen of the city, then called Ninevah, which was part of the great Assyrian Empire. Queen Shamiram was rumored to be a sorceress, the daughter of a fish goddess, and is famous for her beauty and sexuality.

On the northernmost banks of the Tigris lived Ara, called “The Beautiful,” Prince of Armenia.

Word of Ara’s beauty had spread across the region, and soon reached Shamiram’s ears. She quickly fell in love with the idea of the handsome Armenian prince. She desired to marry him, and began lavishing him with gifts. He would be her second husband. Sources say her first, Ninus, left her in a rage because of her infidelity; others say he was killed in battle.

Ara was already married. He refused Shamiram’s proposal and, one by one, sent her messengers and the tokens they brought back to her.

***

There’s a name for people like Larry Mowat who aren’t Armenian: odar.

I learned it at AYF Camp Haiastan, where my cousins, brothers and I went later that summer. One of the counselors—we called them unger or ungeroui, the word for “friend” or “comrade” in Armenian—was a non-Armenian. Everyone gossiped about the odar. They wondered why he’d want to be a counselor at an Armenian summer camp if he wasn’t Armenian.

He left after the first week. No one was surprised, really, me least of all. I felt bad for him. Armenians have a way of knowing each other, mostly through the church but also through youth organizations like Armenian Church Youth Organization of America (ACYOA) or the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF). I quickly discovered that most of the campers not only knew each other, but had also been going to Camp Haiastan since they were little. And, many of them spoke Armenian. I’d always been jealous of my classmates at school who could speak more than one language. I had a strange childhood fantasy of needing to call my parents from school and switching to Armenian to communicate with whoever answered the phone.

Being at camp, I was glad that I knew at least a little bit. I’d spent the last two years walking up to the Armenian Church with my brothers to take language lessons. Our teacher’s name was Miss Emma. We’d meet her, my dad, and a few other students in one of the Sunday School rooms and practice writing and speaking. She taught us simple words like gndak (ball), kapik (monkey), and lolik (tomato). This was enough vocabulary for me to parse aghchik shun, something I kept hearing some of the older campers saying to one another. Aghchik is girl; shun means dog.

Still, more often than not, my brothers, cousins and I were lost. We mouthed our way through morning prayers: the Hayr Mer, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Jashagestsook, a prayer said before meals. I didn’t know the steps to the dances at the camp socials. I’d even missed out on the history, hearing about things like the Battle of Sardarabad for the first time when my cabin sang a song about it on Song Night.

Even though I’d been to Armenia, eaten plenty of chorek and pilaf and kebabs, even though I had an Armenian name and Armenian blood, I was something of an odar at Camp Haiastan. My friends referred to me as the albino, albeit endearingly. My blue eyes stood out in the sea of brown ones, winning me an award for best eyes by default.

***

Shamiram was outraged but undeterred. She led an army to Armenia to kidnap Prince Ara. Though she and her soldiers won the battle, Ara was killed in the fighting. Devastated, Shamiram called on the gods to resurrect him.

“I have prayed to the gods to lick his wounds and heal him,” she told the angry Armenians, “Ara will revive.”

He didn’t and, devastated, Ara’s countrymen tried to avenge their Prince’s death.

***

I’m talking about myself as different. Having studied difference and outsiders in history and literature, I feel uncomfortable using this word. I am blonde-haired, blue-eyed, white, American, native English-speaker. But I’m also something of an odar outside of camp because of my name.

“What was that?” I repeat it two, three, four times. They say, “Where is that from?” or “That’s a unique name.” They try to sound it out. “ShAM-ee?” “ShAR-mee?” “Sham-ee-RA?”

“ShAHmee,” I say. I’d repeat it over and over on the first day of school each year. By high school, I learned to raise my hand and say “Shami” when teachers paused at the “Sh.” I avoided pronouncing the full “ShAH-mee-RAHm” because I felt embarrassed.

As I’ve gotten older, it’s not the uniqueness of my name that shocks people, but the fact that my remarkably non-Armenian face is attached to it. When students sign up for tutoring appointments with me, there is no picture next to my name. More than one, at some point in the session have said something like, “I thought you would be Indian.” One of those was Indian himself. A boss I had a few summers ago thought she’d brought the wrong resume to my job interview.

The place where I am proud of my name is amongst my family, as I am named for one of its most endeared members. My great grandmother Shamiram was a source of incredible strength and love in the Barooshian family, and she is still spoken of as such, missed by everyone who knew her.

I learned recently that friends and acquaintances that couldn’t pronounce or spell her name called her Charlotte. I go by Sarah, but only at Starbucks and Panera and other places that ask for a name to go with your order. It’s easier than spelling out Shami three times and then cringing as the person who puts my order on the counter fumbles over the pronunciation. Sometimes, when I say Sarah, they ask “with or without the h?” and I don’t know how to respond.

When I was younger, it used to drive me crazy that my name wasn’t on keychains and stationery. Now it feels special. I’ve never met another Shami or Shamiram, so it’s a conversation piece, a topic for my college essay, something memorable. Sometimes it’s nice to feel like one in a million.

***

To stop the fighting, Shamiram dressed one of her men as Ara and presented him before the Armenians, who believed her magic had saved him. Legend has it that, on her return to Ninevah, Shamiram buried Ara at the foot of Mount Ararat and his spirit rose, giving the mountain the shape of his sleeping form.

***

I’m not one hundred percent Armenian, by blood or in practice. I go to the Armenian Church on rare occasions, my language skills are no better than they were at camp, and I don’t participate in the network of Armenian youth in my area—partly out of shyness, partly because I don’t speak the language or go to church, and partly because they do and are closer because of it. Who am I to call myself Armenian, except that my name suggests it?

And even the name Shamiram is not a name common among Armenians because Shamiram herself was not Armenian. She was an Assyrian Queen who plays a part in an old legend about an Armenian prince named Ara. She fell in love with him but he didn’t return the affection, so she did what was sensible in the ninth century BCE and invaded.

I think about that word—invasion—as I write about Armenian people, food, traditions, and secrets, and me with only a 25 percent claim to them.