Special for the Armenian Weekly

I am Bolsahye—my Armenian parents were born in Istanbul, or Bolis. Sometimes when I tell other Armenians this, I am met with a terse “oh,” and the conversation quickly dissipates.

Sometimes people are genuinely confused and do not understand why my last name is Cinar and does not end in “–ian”. I still remember an instance in elementary school when my cousin and all the other Bolsahye students in his Armenian school class were withheld an invite to their Aleppo-Armenian classmate’s birthday party. Worst of all, I have been told straightforwardly and in all seriousness that people like me are not “real Armenians”.

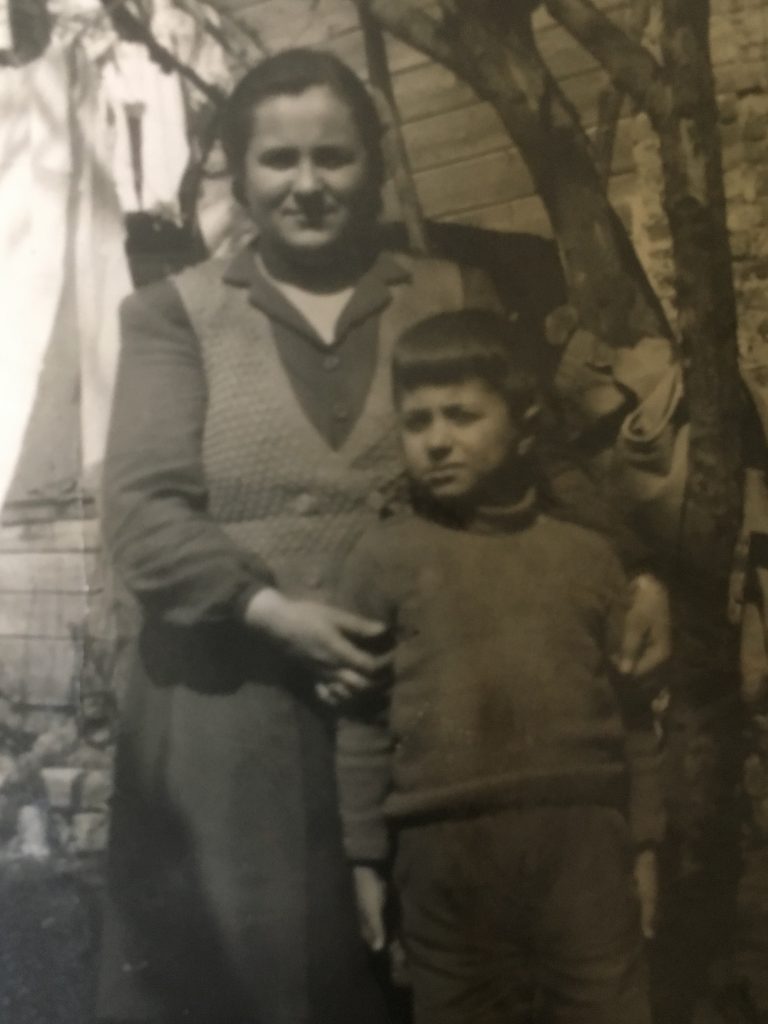

Hagop Yassi (the author’s grandfather) and his mother, Zaruhi, in Samatya, Istanbul, circa 1948 (Photo courtesy of Lori Cinar)

Yes, people really do say those things.

They say them because of the misconception that anything that has to do with Turkey is inherently bad. You might be thinking “there’s no way that people are so closed minded that they would tell you you’re not a ‘real Armenian’. That sounds like a taunt from a first grader!” Well, the answer is yes. The people who say things like this are among us. They are well educated and well liked. They sit next to us in church and send their children to camp with ours. They are Armenians who choose to isolate their own kind on the basis of where they are from. It may sound ridiculous, but it is very real and I want to explain why I believe it needs to stop.

I would like to give the aforementioned individuals the benefit of the doubt. Most people who are not Bolsahye do not necessarily understand or think about what it was like to be an Armenian who stayed in Turkey after the Armenian Genocide. Most Armenians fled their homelands—by choice or by force—to other nations that welcomed them, for the most part, with open arms. These Armenians were free to worship, speak, teach, and generally continue living their lives free to be Armenian. They opened schools, carried on our culture, created literature and art, all in Armenian. They were able to bear their name—one of the most basic human experiences—with pride and without fear.

My family could not do any of these things. Mine and countless other families in Istanbul did not have the luxury of being able to speak and worship in their own language as often or as openly as they pleased, something other diasporan Armenians may take for granted. Bolsahyes were forced to veil their Armenian identities and incorporate the Turkish language and culture into their lives as a means of survival.

The misconception that we are more sympathetic to Turkish culture should be replaced with giving credit for building a large and active Armenian community in a country where we are clearly an unwanted minority.

Perhaps this circumstance might be better explained with an example. My grandfather was born in Istanbul and was given the name Hagop at birth. When his parents filed for a birth certificate, his name was conveniently misspelled as ‘Agop Yassi’ (this was an all too common practice by the Turkish government as an effort to thwart the retention of Armenian-ness. My father’s given name is Avedis but was reported as Avadiz on his birth certificate). And so, Agop Yassi went through his life as an Armenian in Istanbul. He carried around the title of “less-than” with him everywhere he went, imposed on him by the nation he was living in. He endured instances of personal and communal persecution and segregation. If he was spotted wearing a cross around his neck or speaking Armenian in public, he was called gyavur (a derogatory Turkish slur which means infidel, akin to calling a black individual the n-word).

Luckily, he had the opportunity to attend an Armenian church where he served in the choir and received an education at the Sahakyan School in Samatya. He kept his head down, married my grandmother, and moved to New Jersey in 1971 after having their daughters Arpine (my mother) and Ani. When he arrived in the U.S., he took full advantage of his newfound freedom and officially changed his name to Hagop Yassian, as it was always meant to be.

Can you imagine being a proud Armenian and living amongst the people who committed those malicious, violent acts against your family? What must he (and the thousands of other Armenians in Turkey) have felt about the continued attempts to dismantle our culture, including forcing him to go by a name that was not Armenian?

The author’s grandparents, Hagop and Tushguhi Yassi, on their wedding day in Istanbul, 1964 (Photo courtesy of Lori Cinar)

I sometimes wonder if the people who condemn Bolsahyes think that any of them felt good or safe or at home in Turkey. Do they think they liked knowing that they lived amongst others who were never taught of the injustices perpetrated against them and instead were taught to hate them? My grandfather says he finally left Turkey because he was tired of being treated like a second-class citizen. And still, even now in America, his own granddaughter and countless other descendants of Bolsahyes have to defend their “Armenian-hood” to our own community.

Armenians born in other parts of the world rarely struggled with issues like this, yet so many of them do not consider that this may be the reason many of us do not bear a “–ian” at the end of our last names.

Other Bolsahyes were not as lucky as my grandfather. Many Armenians in Turkey did not have access to local churches, could not afford to send their children to private Armenian schools, or felt generally unsafe making any public indication that they were Armenian. In fact, many of my more senior family members cannot communicate with me in Armenian at all because they never had the opportunity to learn or speak it. Yet that does not change the fact that these individuals staunchly remained close to their roots, living only within the Armenian community, marrying fellow Armenians, and sending their own children to Armenian school when they could. So what makes these Armenians any less than the rest? They still held onto their identity even when they were not allowed to express it which, to me, translates to doing the best they could under the circumstances.

Many Armenians I know can speak Arabic, Russian, or a variety of other languages because of the spread of our people. As the saying goes, “Kani lezoo kides, aytkan mart es” (“The more languages you know, the better person you are”), and I wholeheartedly agree. But why is it acceptable for other diasporans to celebrate the languages, cultures, and foods of the places they and their parents grew up while they would prefer that my family just forget everything about where we came from? Of course, most Bolsahyes do not have the intention of promoting the Turkish culture. We clearly recognize it as the culture of our oppressors and we have felt that oppression even more recently than others have. We simply want to be able to enjoy being Armenian the same way everyone else does.

The single issue about Bolsahyes that really causes me the most strife is this: if my parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents had the bravery to maintain their faith and their identity within a state that continues to deny the Armenian Genocide, while still producing hayaser families who continue to promote their Armenian heritage, what exactly have they done wrong? What makes us any less than Armenians who are from Egypt or France or Iran?

Yes, my grandfather might still watch the news on Turkish television, and yes my father still speaks Turkish amongst his friends and family, but these are not sins. Do those actions negate the fact that they learned the Armenian language in a country that basically forbade it? Does it render my grandfather’s six grandchildren – who all actively participate in their Armenian community, churches, and schools – unworthy of calling themselves Armenians? Does the occasional purchase from a local Turkish supermarket make my grandmother a traitor even though she uses those groceries to prepare Armenian meals for her family?

In saying all of this, I am by no means promoting Turkish goods, tangible or intangible. What I am trying to argue for, though, is that some Bolsahyes consume these Turkish products—like movies or language—for their familiarity. It’s part of how they grew up and what they’re used to. We can’t expect them to not have assimilated to Istanbul culture at all. Even decades before the Armenian Genocide a great many Armenians who were living throughout the Ottoman Empire spoke and read Ottoman Turkish simply because they lived there. Haven’t you ever heard a song from when you were younger and been suddenly filled with fond memories? Telling Bolsahyes that they are less Armenian for having these basic human feelings is almost like telling a black man in America that he should be ashamed for enjoying the songs of his childhood because they are the songs of the white man. Shouldn’t he be allowed to participate in the culture in which he lives and at the same time maintain his own personal roots? When my father says he remembers a certain song from his teenage years in Turkey, I see no reason to be upset by it.

The author’s grandparents, Hagop and Tushguhi Yassi, and mother Arpine in Istanbul, 1970, Istanbul (Photo courtesy of Lori Cinar)

The reason that I chose to express all of these thoughts is because of a Facebook post that sparked a decisive conversation within my friend group. A fellow Armenian posted a status condemning those who supported Turkish food products in grocery stores and went so far as to say that those individuals “made [him] sick”. He placed blame on Armenians who still live in Turkey for assimilating in a country whose government destroyed our people and culture. I wished there were a way that I could scream through my laptop screen. How could he possibly place blame on Armenians for assimilating to the culture of the place where they live? Are they not brave for remaining Armenian in a country where the odds continue to remain stacked against them?

The heroic efforts of Istanbul-Armenian individuals like Hrant Dink and Garo Paylan, who risk their lives working hard to maintain our rights and heritage in Turkey, garner a great deal of attention from the greater Armenian community. While a great many Diapsoran Armenians think of them as heroes, they forget to acknowledge that these men are the products of the same Istanbul-Armenian community that I am from. Hrant Dink wore Turkish clothing and Garo Paylan probably dances to Turkish music. It does not make either of them any less Armenian.

That is why I would like to pose a question to the Armenians, wherever they maybe—why are we being so unfair to one another? To think of any Bolsahye (or any hye, for that matter) behavior as shameful is only perpetuating the hateful view that the Ottomans had of us all 102 years ago.

Just because your family fled and mine had the misfortune of having to stay does not make us different. When Armenians segregate and ostracize one another, that is when the plan for our people’s destruction succeeds.

When our community becomes more understanding of all of our different backgrounds and the different struggles that all of our people have gone through, only then will we be able grow and prosper.

As a first generation American, my parents never raised me as anything but Armenian, and that is how I live my life. I am only ever an Armenian.