The Armenian Weekly’s Exclusive Interview with Artsakh Ombudsman Ruben Melikyan

On March 9, Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabagh) Ombudsman (Human Rights Defender) Ruben Melikyan met with the editors and staff of the Hairenik Weekly and Armenian Weekly newspapers, as a part of his tour of the Eastern United States.

On March 9, Artsakh Ombudsman Ruben Melikyan met with the editors and staff of the Hairenik Weekly and Armenian Weekly newspapers, at the Hairenik headquarters in Watertown, Mass. (Photo: The Armenian Weekly/Rupen Janbazian)

Upon entering the doors of the Hairenik headquarters in Watertown, Mass., the Ombudsman immediately felt a sense of familiarity. “I always feel like I’m at home when visiting Armenian institutions,” Melikyan said, admiring a historic photo of a delegation of the First Republic of Armenia visiting Massachusetts in 1919.

Melikyan is no stranger to the Boston-area. An alumnus of Tuft University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy Tavitian Program, he spent quite a bit of time in what he calls his “second favorite” city, back in 2008.

Since May 2016, Melikyan has lived in Stepanakert after he decided to take the job as the small nation’s Human Rights Defender—a decision, he says, was very easy to make.

At the Hairenik, Melikyan candidly spoke about his responsibilities, the challenges he faces, and his prospects for the future of Artsakh. He also detailed the importance of the Armenian Diaspora and the role it can play in Artsakh.

“One of [Artsakh’s] main advantages is the Armenian Diaspora—Spyurk. From the very beginning, I started to find ways to cooperate with the Diaspora by working with various different groups within it. I’m open to cooperate with any group, for the sake of the people of Nagorno-Karabagh and for the sake of human rights,” he explained.

According to Melikyan, one of the biggest problems in the Artsakh conflict is the lack of international presence there, mostly because of its unrecognized status. “For political reasons, some may not recognize the reality—not recognize Nagorno-Karabagh as the independent country it is. But no one can deny people,” Melikyan said.

“There’s a new type of discrimination that we face, one that is not connected to skin color or language, but connected to the political status of the country. Artsakh cannot be discriminated against for that… We are strong enough to do anything, but it is vital to bring the international community to Artsakh,” he added.

Below is the interview with Melikyan in its entirety.

***

The Armenian Weekly: Welcome to back to Boston.

Ruben Melikyan: Boston’s probably my second favorite city… After my city.

A.W.: And where is your city?

R.M.: Yerevan. I was born and raised there. I moved to Artsakh after the April War. I probably have Artsakhi origins, though. My grandfather’s surname was Melik-Israelian, and the Melik-Israelians were one of the five Melikdoms of Artsakh. I’m not certain, though. I’m a lawyer. I need evidence.

A.W.: Maybe that is what made you end up in Artsakh.

R.M.: When I was a child, my father’s family always spoke about this possible heritage and that is why Artsakh has always been very important to me. When I became the first head of the newly established Academy of Justice of Armenia—the institution for initial and continuous training for judges, prosecutors, investigators—in 2013, one of the first things I did was establish contact with relevant Artsakh authorities in order to cooperate and have the same thing for Artsakh.

This is very important, because unfortunately, Artsakh is outside many of the processes that are in Armenia. Armenia has very good ties with European, American non-governmental organizations (NGO), government organizations in the justice and human rights spheres. There are many capacity-building initiatives there. Unfortunately, they don’t cover Artsakh because of political reasons.

After the April War erupted, I got a call. It was mid-April and I was invited to work in Nagorno-Karabagh. They told me I had a couple of days to think about it and discuss it with my family. I told them right away that I didn’t need two days. I figured if they suggested and thought I was the best candidate, I wouldn’t be able to look myself in the mirror if I refused.

A.W.: Who’s they?

R.M.: The way it works in Artsakh is parliamentarians suggest the candidacy and then the Parliament approves. In some countries, the President appoints an Ombudsman, but not in Artsakh. So, I told them right away I was on board and the process started. On May 5, 2016, I was approved by Parliament and I began my work right away.

A.W.: You mentioned political reasons standing in the way of capacity building. How has non-recognition affected your work?

R.M.: In Artsakh, we have several disadvantages because of non-recognition issues, but we also have several advantages as well. I wanted to recognize them right away.

One of the main advantages is the Armenian Diaspora—Spyurk. From the very beginning, I started to find ways to cooperate with the Diaspora by working with various different groups within it. I’m open to cooperate with any group, for the sake of the people of Nagorno-Karabagh and for the sake of human rights.

My first international visit as Ombudsman was in the summer of 2016, when the Armenian National Committee of Europe (The European Armenian Federation for Justice and Democracy-EAFJD) invited me to Europe for some very productive meetings.

Then, other organizations also started to cooperate. For example, the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) recently invited me to Europe again. There, I held a press conference in the European Parliament and had an open meeting with civil society in Brussels, with many people—including Azerbaijanis—in attendance.

We have some other things in the works. I can’t confirm, but I will say that we are currently working with a Diasporan organization on a new report of the April 2016 events.

It’s a strategic decision to directly cooperate with the Diaspora and to have the Diaspora engaged in Artsakh. My first priority is engagement. Unfortunately, many people in the Motherland treat the Diaspora only as people who have money. I treat the Diaspora as people who have ideas, passion, devotion, networks—which is the most important asset we could ever dream of.

A.W.: Are you able to freely engage with other Ombudsmen?

R.M.: We try to be engaged and involved in European and global Ombudsman and human rights networks. My predecessor succeeded, for example, in the European Ombudsman Institute, and our institution has been a member of that platform for four years. Just recently, we had a meeting with the head of the European Ombudsman Institute.

I’m not a politician. I’ve never been a member of any party. I’m a specialist of the law. For political reasons, some may not recognize the reality—not recognize Nagorno-Karabagh as the independent country it is. But no one can deny people. People are always there and they cannot be in a worse position than others.

There’s a new type of discrimination that we face, one that is not connected to skin color or language, but connected to the political status of the country. Artsakh cannot be discriminated against for that.

The recent developments in Artsakh, especially Azerbaijan’s policy of first blacklisting and now prosecuting people who just visit Artsakh, is just one way the discrimination is not properly assessed by the international community. This is one of the messages I try to convey.

Another thing that I am working on is the issue of the April events.

A.W.: Tell us about that. You released two reports on the events of last April.

R.M.: I have been working on the issue of the April events having two things in mind. First of all, there are no international institutions, NGOs, or human rights organizations that offered to do a fact-finding mission or to release a report on what happened. Its’ unfortunate. That is why I had to take it upon myself.

Some might say, “but you are not impartial.” Indeed, I can be perceived as being biased. I am Armenian, and I am proud of being Armenian. That is the reality. But when there is no one reporting on [the Azerbaijani atrocities], I had to do it.

I conducted fact-finding missions abiding by international standards. I openly talk about it and tell international organizations that if they are ready to come to Artsakh and to monitor what is going on, we would be happy to have them. The developments showed that, unfortunately, there are still no international organizations that are ready to do so.

It’s not a coincidence that the day I selected to publish the report was Dec. 9—the international day of Genocide Prevention designated by the United Nations through an Armenian initiative. That press conference was in Talish village, which was totally destroyed because of the April War.

Important work is being done and my mission here is to spread the word about it—to get the attention of human rights organizations and to show them that they are needed in Artsakh. The mere presence of them can be seen as a guarantee for Azerbaijan not to carry out the same atrocities it did last year.

We have videos that people in Azerbaijan uploaded to different social media platforms. They were deleted after a while, but we had already downloaded them. There are some terrible things in those videos. We prepared English subtitles and blurred out faces so that they can be used without any problems. We will publish them.

At the end of February, there was another escalation of the situation in Artsakh. Azerbaijani forces tried to do the same thing they did last April, but failed. Fortunately, this time around things were different. All the donations that came in after the April War went to the right places. When the [Azerbaijani side] suffered the loss in February, they began to throw anti-Armenian hate speech all over the internet, and even uploaded new material from the April War. One of the new videos even shows Azerbaijani soldiers threatening to commit genocide against the Armenian people. There is evidence of clear Armenophobia and intent, and that evidence was provided by them, just a week ago.

The situation is serious and the international community must pay attention to it.

A.W.: What purpose will the presence of international human rights organizations serve? Will the current situation change?

R.M.: Their presence will serve two purposes. First of all, Azerbaijan will possibly think twice about attacking and carrying out atrocities again.

Secondly, their presence will be very important for Artsakh’s society itself. We need international standards to be set in Artsakh. Although many observers say that the situation is good overall, I’m not satisfied. I know that there are many things that have been created in North America, Europe, and the Western world that we can use in Artsakh—mechanisms, structures, and so on. Capacity-building should be a top priority for us. The involvement of international human rights organizations can help bring that capacity building to Artsakh.

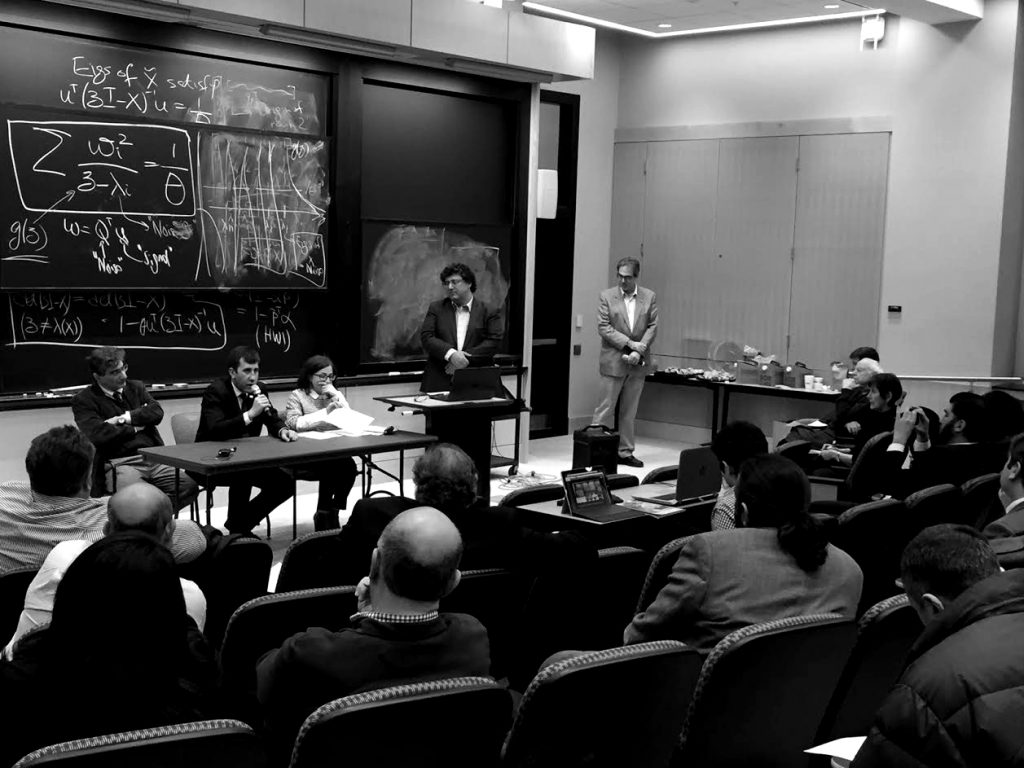

A.W.: Aside from planned meetings, you’re in the Boston area to take part in a panel being held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) called “The Four Day War and its Aftermath—Perspectives on Security, Diplomacy, and the Prospects for a Lasting Peace.”

R.M.: We use the term April War, because there were escalations until the end of April. The aggression didn’t simply stop after the four days. My predecessor’s second report detailed the shelling of Martakert, Talish, and other areas.

A.W.: Is there hope for a lasting peace?

R.M.: Unfortunately the numbers show that Azerbaijan has not changed their strategy. It may have changed its tactics, it has become more aggressive, but their strategy has not changed.

A.W.: What is their strategy?

R.M.: Their strategy is that they want everything. Many Artsakh Defense Army servicemen were killed and wounded since April. There were some escalation periods as well, the last one being in the end of February.

Azerbaijan continuously increases the caliber of their weaponry and in the February attack, it was clear who started the attack. They tried, but were completely crushed. At least six of its servicemen were killed—five in the field and one in hospital. Unfortunately, statements from the international community—including those from the OSCE Minsk Group—don’t put the blame where it belongs.

A.W.: You were quick to condemn Belarus’ decision to extradite Russian-Isreali blogger Alexander Lapshin. You called his prosecution an “attack free speech and freedom of movement” and called the case a “black-and-white issue.” You also called for human rights defenders and journalists to visit Artsakh more as a response.

R.M.: I handled that case very seriously, not only because of Mr. Lapshin’s destiny—the fact that he is being for prosecuted for visiting Artsakh and speaking about its independence, which is very important—but also because his case is clearly being used by Azerbaijan to threaten others not to visit Artsakh, not to engage with Artsakh, and not even to talk about Artakh’s people’s lawful aspirations. The evidence is very clear there. I am sure you remember the photos of Mr. Lapshin being arrested at the Baku airport. He was treated like world’s most wanted terrorist.

As soon as those pictures of his arrest emerged, tens if not hundreds of emails were sent to people who are blacklisted by Azerbaijan with threats that this could happen to them; that this could become their destiny. This is clearly being used by them.

There is a state-backed policy to threaten people. While it is understandable that people will avoid Artsakh as a result, my concept is that we must find people—honest journalists, human rights activists—who will focus on Artsakh issues because of cases like this. We’ve been finding success, but we must continue working on this. The Diaspora can be a great partner in this work—to bring people’s attention to this problem.

A.W.: What has been successful so far?

R.M.: The recent referendum in Artsakh showed positive steps in this regard. There was more of [an international] presence there. I believe that was the reason why Azerbaijan, on the very day following the referendum, announced that it will start a criminal prosecution against some European Parliamentarians. Everyone who tries to even engage with Artsakh suddenly becomes a target.

For the human rights community, this should and must be condemned in very strong terms. There are many condemnations, but we need to go further and use this situation to highlight the problems.

A.W.: Azerbaijani authorities repeatedly accuse the Armenian side of being the aggressor. How does your office respond to such accusations?

R.M.: Azerbaijan has made several accusations of Armenian aggression. I have made it very clear through public statements that if there is any evidence of that, I am willing to hear it. I published my contact information and they can contact me directly, or publish it publicly. I am a human rights defender, not an Armenian-rights defender. This is my job and I am going to handle it.

That statement was made on Dec. 31 and there has been no reaction since. I am still here, ready to handle it. War crimes are war crimes for everybody. We cannot tolerate any war crimes. The fact remains that there are still no details and no evidence.

Melikyan at the Hairenik. The Ombudsman wished to pose in front of the historic photo of a delegation of the First Republic of Armenia visiting Massachusetts in 1919. (L to R) Rupen Janbazian, Michael Mensoian, Zaven Torigian, Ruben Melikyan, Dickran Khodanian (Photo: Tsoleen Sarian)

Unfortunately, there aren’t any independent bodies to come and assess the situation. It’s a vicious cycle and I’m trying my best to break it by reporting in the most professional level I can. The report took more than six months, including many on-site visits, media monitoring, consultations with military and technical experts, requesting documentations from relevant authorities, interviews, and so forth. These are the internationally designated ways of reporting.

Yes, I am Armenian, but try to be as impartial as possible. This is why it’s so important to have other people there. Come and check. Go to Azerbaijan and check their evidence.

The most important thing with the Artsakh conflict is that unlike all other conflicts, there is one fundamental difference: Armenophobia. There is an unacceptable level of Armenophobia in Azerbaijani society.

A.W.: You visited captured Azerbaijani serviceman Elnur Huseynzade in early February, just a couple days after his capture. You said in a statement that Huseynzade had been provided with a public defender, a translator, and treated with dignity. What was the reaction from the Azerbaijani side regarding this?

R.M.: When we announced that I had visited him, the best reaction I received in the comments section from Azerbaijan was cursing. There was not even one neutral opinion about what I had done. Azerbaijani authorities never do the same to captured Armenian soldiers—they never guarantee their well-being. In my statement, I said that I am ready to do my best to guarantee [him] a lawyer of his choice. We are trying to create a culture of law and everyone has the right to defense. We do these sort of things and the reaction from Azerbaijan is always negative.

I will give you another example. My counterpart in Azerbaijan, the person responsible for human rights protection there, had a public statement saying, “Ramil Safarov must become an example of patriotism for the Azerbaijani youth.”

The situation is different from all other conflicts and we need to make the international community understand this. It’s not a normal situation and anything could happen. We must all do our best to ensure that no more lives are lost.

A.W.: If you were to note one major change in the Artsakh conflict since last April, what would it be?

R.M.: I know that our soldiers are morally stronger since last April. April showed that we are united—Armenia, the Diaspora, and Artsakh are united. People in Artsakh say that during two days in April more people came there then the entire 1990’s.

‘I know that our soldiers are morally stronger since last April. April showed that we are united—Armenia, the Diaspora, and Artsakh are united.’ (Photo: ‘We Are Our Mountains’ monument in Stepanakert, Artsakh – Araz Chiloyan)

We are strong enough to do anything, but it is vital to bring the international community to Artsakh. The presence of international human rights organizations is lacking, and we need to address that. That’s my mission.