Special for the Armenian Weekly

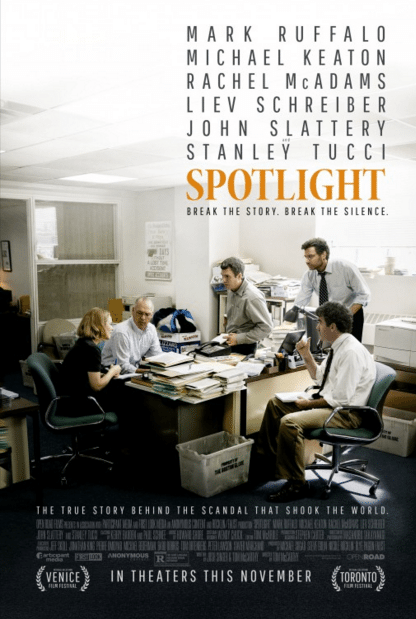

It’s no secret by now that Boston has been Hollywood’s darling for the past few years. Just this fall, two Boston-themed movies have been released. For once, one of them wasn’t about Whitey Bulger. Released to rave reviews on Nov. 6, “Spotlight” stood out as a very different sort of “Boston movie.” Part of what sets it apart is that the story it portrays likely would never have been known had it not been for the tireless work of two Boston-area Armenians: veteran reporter Stephen Kurkjian and attorney Mitchell Garabedian.

Set in 2001, the film centers on the Spotlight team at the Boston Globe, the investigative team that has broken many of the city’s most defining stories. At that time, the team, made up of Walter “Robby” Robinson, Sacha Pfeiffer, Michael Rezendes, Ben Bradlee Jr., and Matt Carroll, was investigating the sex abuse scandal in the Catholic Church, the discovery of which would ricochet around the world. But in early 2001, no one knew that the problem extended beyond Boston, and the reporters were as shocked as the public when the extent of the abuse within Boston alone was brought to light.

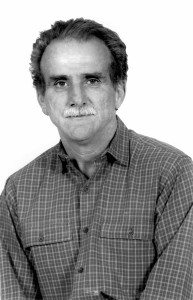

The cracks in the surface of the church’s reputation had begun to emerge in 1992, when Kurkjian investigated the case of James Porter, a priest in Fall River, Mass., who was convicted in 1993 of molesting 28 children and sentenced to 18-20 years in prison. Though Kurkjian discovered a handful of other priests between 1992 and 1993, who followed the same pattern of repeat abuse and quiet reassignments to new parishes, he had no inkling of the scope of the church’s cover-up.

Kurkjian, portrayed in the film by Gene Amoroso, worked as a reporter for the Boston Globe for 40 years and was a founding member of the Spotlight team in 1970 before relocating to Washington, D.C., to become chief of the paper’s Washington bureau. He returned to the Spotlight team shortly after the story on the sex abuse scandal broke and the team was flooded with calls from former victims. In the film version, this is right about when the credits begin to roll, but as Kurkjian can attest, there’s quite an epilogue.

Kurkjian had been busy with post-September 11 coverage in mid-January 2002 when he was reassigned to the Spotlight team. The team’s work was so secretive that even a fellow Globe reporter like Kurkjian didn’t know what the team had been working on until the public did. One of the film’s most climactic scenes is one in which Rachel McAdams’ Pfeiffer confronts a former priest named Father Paquin on his doorstep about accusations that he molested young boys. In reality, that encounter took place some time after the story broke, and Kurkjian was the reporter who obtained Paquin’s chilling confession by showing up outside his door in Medford, Mass., one Friday evening. “The killer thing that he said to me was, ‘I never got pleasure, I gave pleasure.’” Paquin pleaded guilty in 2002 to molesting at least 14 boys, but was released from prison this past October.

The film has been accused of minimizing Kurkjian’s role in uncovering the scandal; Kevin Cullen of the Boston Globe wrote in a Nov. 22 column that Kurkjian, “a journalistic icon,” was unjustly “portrayed as a curmudgeon who was dismissive of the importance of the story. That couldn’t be further from the truth, and Kurkjian did some of the most important reporting as part of the team that won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for exposing the coverup.” That Pulitzer Prize was Kurkjian’s third, which speaks more convincingly to his credentials than a Hollywood script ever could.

Indeed, the Paquin interview wasn’t Kurkjian’s only startling confrontation while covering the story. In the wake of the scandal, Cardinal Bernard Law, then the bishop of the Boston Archdiocese, had all but disappeared from public view. Kurkjian, who had interviewed Law before, heard from a friend that he would be presiding over the funeral mass of an elderly priest in Belmont, Mass. After the mass, Kurkjian asked a priest if he could speak to Law, and was told that if he met him by his car outside, he would be able to talk to him briefly.

“So I went out, and I said, ‘Cardinal, where have you been?’ And he came out and he was sneering…and he said, ‘I’m going to the Vatican tomorrow.’” Kurkjian asked Law several questions, all of which he evaded. Law left Boston the next day for what turned out to be an even more influential position at the Vatican.

Ultimately, Kurkjian says, the Catholic Church failed in its part of the social compact. “One of the ways I gauge how good a scandal could be is by looking at what the institution’s—the goal of the institution that’s involved in the scandal—is. And here you had the Catholic Church, that is dedicated to the faith and children, and the wrong that’s involved here was the injuring of children. So that’s really a basic disconnect, a basic deceit of the goal of the institution…and the secrecy of the church condoned and furthered the wrongdoing.”

As depicted in the film, many of the documents that ultimately allowed the Spotlight team to piece together the extent of the sex abuse scandal and break the story only surfaced due to the tenacious legal work of attorney Mitchell Garabedian. Garabedian, whose character is portrayed in the film by Stanley Tucci, was instrumental in the publicizing of the scandal due to his refusal to allow the abuse victims he represented to sign confidentiality agreements in return for settlements from the Catholic Church. Numerous victims over the years had been advised to sign these agreements by other attorneys, who saw them as the only way their clients would get any sort of compensation.

Attorney Eric MacLeish, also depicted in the movie, led many of his clients to sign such agreements. He has criticized his portrayal, writing in a Facebook post that such settlements were an “absolute condition” if victims hoped to get anything out of the church. What they got were typically small settlements, limited by state law that capped suits against charitable organizations at $20,000.

However, MacLeish’s claims of an absolute condition fail to explain how Garabedian managed to win cases against the church without submitting to confidentiality agreements, or how he managed to legally maneuver around the $20,000 settlement cap. MacLeish subsequently alleged to the Boston Globe in 2010 that he himself had been a victim of multiple, separate instances of sexual abuse as a child, which he claims precipitated severe post-traumatic stress disorder and his subsequent departure from the law.

It’s hard to know exactly what enabled Garabedian to achieve such a starkly different result for his clients, but in what will be one of the film’s most memorable scenes for any Armenian viewer, his character credits it to his being “an outsider.” In the scene, Stanley Tucci’s Garabedian and Mark Ruffalo’s Rezendes are sitting together in a diner discussing the developing story, and Tucci remarks that the scandal took so long to be brought to light because it needed the perspective of outsiders, in the form of Marty Baron, the Globe’s Jewish editor, and Garabedian, an Armenian. In one of the film’s few hard-to-believe lines, Tucci quips, “How many Armenians do you know in Boston?”

The real-life Garabedian, who has been a practicing attorney since 1979, credits his success in part to a “very solid foundation as a child in my Armenian upbringing, socially, religiously, and otherwise. I think my upbringing helped in terms of seeing right from wrong, in terms of having the foundation to proceed.”

Such strength was necessary in the face of a ruthless retaliation from the church, which even resorted to having documents “disappear” from court files. “The Catholic Church, which is the richest institution in the world, was obviously asserting its power wherever it could to keep these matters silent. But they couldn’t control me, as an outsider. They threw everything they had at me, they threw every kitchen sink they had at me during the litigation, and they tried to have me sanctioned three times before the judge so that my license to practice law could be jeopardized. But it didn’t work.”

The film, according to Garabedian, offers a fairly accurate depiction of the legal process that was involved. Garabedian became involved in cases against the Catholic Church beginning in the mid-1990’s, when he was approached by victims of Father John J. Geoghan. “The Catholic Church [was] trying to hold itself out as a moral institution, as the most moral institution in the world, when actually it was the most immoral—there’s no excuse for allowing innocent children to be sexually molested. It showed that the church had serial pedophiles, and serial enablers of pedophiles.”

As the case grew from the first suit against Geoghan, filed in 1996, Garabedian came to represent 86 of Geoghan’s victims in a years-long process that included depositions of Cardinal Law and other high-ranking members of the Boston Archdiocese. In 2002, the victims were awarded a $10 million settlement. The following year, Garabedian represented 120 additional victims as part of a larger suit brought by a number of attorneys that resulted in a record-setting $85 million settlement with the Catholic Church. This and other subsequent settlements forced the church to sell large amounts of real estate and, in some cases, seek bankruptcy protection.

Garabedian went on to win a $12 million settlement in 2013 for 24 victims of former Jesuit priest Douglas Perlitz, who was convicted of abusing numerous boys at Project Pierre Toussaint School in Cap-Haitien, Haiti, and continues to represent Haitian abuse victims today. “Victims are pouring into my office from around the world. For instance, I represent 146 victims who were sexually abused, not by a priest, but at a Jesuit school in Haiti. He [Perlitz] got almost 20 years in prison on a plea.”

In spite of his numerous victories on behalf of victims of abuse, Garabedian takes a dim view of the church’s prospects for redemption. “You’re dealing with an entity that has allowed tens of thousands of children to be sexually molested by pedophiles, and the enablers and supervisors have allowed tens of thousands of children [to be abused] over the course of decades and decades, and it’s only surfaced because they got caught…they continue to try to hide it. … If this wasn’t the church, if this was another group…why wouldn’t they be prosecuted?”

“Victims are still coming forward, and I think the victims who were sexually molested in the early 2000’s, late ‘90s haven’t reached the age where they’re old enough to come forward. I think the Catholic Church is a world unto itself and they feel as though in an odd way, they’re the victims, and they’re going to assert their influence and power to protect themselves… I think the Catholic Church thinks in terms of, as I said in the movie, in terms of centuries, and that this will all blow over, and they’ll try to rewrite history as the victims.”