An Interview with Karine Shnorhokian and Ron Levitsky

Special for the Armenian Weekly

The Near East Foundation (NEF), the successor organization of the Near East Relief (NER), recently partnered with the Genocide Education Project (GenED) and the Armenian Genocide Justice (AGJ) 2015 Committee of the Armenian Cultural Association of America to produce an educational curriculum that provides high school teachers with a companion lesson guide on the NER and America’s humanitarian response to the Armenian Genocide.

Armenian orphans of the Near East Foundation’s orphanage in Alexandrapol (Photo: Near East Foundation)

The Armenian Weekly spoke with Karine Shnorhokian, head of the Education Subcommittee of the AGJ, and Ron Levitsky, head author of the curriculum, to discuss the “They Shall Not Perish: The Story of Near East Relief” teacher’s guide. The education subcommittee has collaborated with key Armenian-American organizations over the years leading up to the Armenian Genocide Centennial to develop projects, programs, and events that contributed to the Centennial commemorations across the country.

“The members of the committee have long been active in providing quality seminars and content for educators on human rights issues, so the development of this curriculum was a natural next step,” Ara Chailian, member of the AGJC, told the Armenian Weekly. Chalian explained that with the efforts of all contributing parties, this example of community and citizen humanitarian activism is being given its proper place in history. “This will give educators another tool to fuel American students’ recognition of their ancestors’ role in world relief efforts and will motivate them to seize the critical moments in history, take a stand, and create movements of activism that change the courses of societies.”

Several important sources of evidence regarding the Armenian Genocide can be found in American consular and diplomatic reports in U.S. State Department records on the internal affairs of the Ottoman Empire. Additionally, headlines and reports that appeared in the U.S. media of the time covered the ongoing genocidal campaign. The plight of the Armenians was making top news throughout the country.

Not only were the American public and government aware of the atrocities taking place against the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, but both were actively working to put an end to the genocide while it was happening.

Many different aid programs, including the popular NER, were raising unprecedented amounts of funds to help save the Armenian people. In 15 years, the NER would raise more than $116 million and mobilize hundreds of volunteers to help the effort.

The NER’s response to reports of “crimes against humanity” against the Armenians and other Christian minorities of the Ottoman Empire is considered to be the United States’ first collective display of overseas humanitarian aid.

This past March, the NEF announced the launch of its traveling exhibition, They Shall Not Perish: The Story of Near East Relief, in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide and of the NEF’s founding. The 27-panel exhibition, which features high-quality reproductions of archival photographs and documents, chronicles the launch and legacy of the NER.

Last month, the NEF also launched the Near East Relief Online Museum, which features digitized collections of photographs, letters, and journal entries pertaining to the relief efforts. The museum aims to serve as a resource for scholars, students, and anyone with an interest in this critical period in American philanthropic history.

Below is the interview with Shnorhokian and Levitsky in its entirety.

***

Rupen Janbazian: How was the idea of the “They Shall Not Perish: The Story of Near East Relief” teacher’s guide conceived?

Karine Shnorhokian: While studying nursing in college, one of my professors read my last name and said to me, “You must be Armenian.” She then explained how growing up, she couldn’t leave the dinner table unless she finished the food on her plate since there were “starving Armenians.” This struck my interest.

Like many Armenians, I was very active in educating others about our story, our struggle, our plight, and our demand for recognition. However, one huge component of our story of 1915 is our survival. And survival of the Armenians would not have happened without the NER’s efforts.

As we mark the Centennial of the Armenian Genocide, I felt a sense of responsibility and a need to shed light and acknowledge the men and women who sacrificed so much to save the “starving” Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks. These orphaned children, who would later become our parents, grandparents, and great grandparents, were eternally grateful.

Though the story of the NER has been told time and time again, there was a need to create a cohesive curriculum that contains all the necessary components for an educator to use in their classroom. With this, we are not only educating about world history, but we are recognizing America’s history and philanthropic efforts, which raised more than $116 million for humanitarian work.

R.J.: Why did you feel it was important to have such a curriculum prepared?

K.S.: In respect to our educators, we understand that teaching history is such a difficult topic, since yesterday’s news becomes tomorrow’s history. We also understand the difficulties of needing to compress hundreds if not thousands of years into one calendar school year.

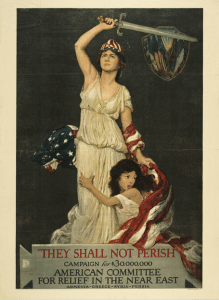

1918 poster by Douglas Volk depicts a young girl, symbolizing the Near East, clinging to the legs of a woman holding a sword and U.S. flag, symbolizing America (Photo: Near East Foundation)

With that being said, the creation of “They Shall Not Perish: The Story of Near East Relief” is unique, since it sheds light on the risk that individuals took during this horrific time to save men, women, and children in their most vulnerable state. It leads to an opportunity to teach our students that there are those that will not idly stand by when mass atrocities are occurring—that we have the power to stop the injustices in the world.

Genocide continues to occur; in the past two decades, genocides in Rwanda, Bosnia, and Darfur have taken place. One day, I know my children will ask me why we did not do something for the innocent victims of these genocides, and I must accept the fact that we, as humanity, did not do enough.

I believe that history repeats itself, and that this curriculum will allow for students to take ownership and responsibility when these crimes happen and be proactive instead of reactive in times of crisis.

R.J.: Why the Near East Relief story?

K.S.: The story of the Near East Relief needed to be told. I have always been fascinated as to how much effort and fundraising went into this relief project. Far too often, we focus and discuss the negative, and although more could have been done during the genocide, the fact that these missionaries set off to unknown and unchartered territories is quite admirable. The fears, concerns, and significant harm that these individuals faced are beyond comprehension.

My nursing background makes me appreciate the compassion, but it also makes me cringe at the number of life-threatening diseases these people were exposed to. Prior to this campaign to help raise money and awareness, no one knew who or what an Armenian was. People had limited knowledge other than media reports of how severe and dire the situation truly was, and yet, these missionaries willingly signed up for this humanitarian mission, going to such great lengths to save people they hardly knew. It makes me proud as a nurse, as an ethnic Armenian, and especially as an American.

Armenians are eternally grateful for this initiative. We will never forget what was done and we thank America for leading such an important initiative. As Americans, this is not something we should hide. We should be proud of this chapter in American history. We should teach our youth that compassion does exist, and not hide behind the fear of threats for keeping quiet and not acknowledging the truth.

R.J.: Why is it important to include lessons on the Near East Relief in an American history or world history class? In what ways will this benefit students?

Ron Levitsky: Much of history has consisted of conflict—political, economic, social, and military. The brutality of human beings toward each other has not been limited to any particular time or place. Among the worst brutalities is genocide. Too often the world stands by and does nothing beyond feeble protest. However, Samantha Power, the current U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and author of A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide, notes that even in times of genocide there are individuals whom she calls “upstanders,” those who risk their careers, safety, and even lives to help victims of genocide.

There are perhaps no greater examples of upstanders than the men and women of the NER. They bore witness to the genocide that the Ottoman and Nationalist Turkish governments denied. These workers fed, clothed, and provided medical treatment to thousands of refugees. They became points of light in a brutal and horrific darkness.

The world can be a frightening place. Sometimes international problems can appear overwhelming, especially to children. It is especially important for teachers to offer historical examples of people who had the courage to be those points of light we want our students to grow up to be. Such were the men and women of the Near East Relief, and the story of their heroism needs to be included in an American or world history class.

R.J.: Who worked on the content for the curriculum? Why were these individuals/groups approached to work on it?

K.S.: In 2003, the Armenian Youth Foundation received a grant to hold an exhibit on the Armenian Genocide at the National Council’s annual Social Studies Conference. It was there that I met hundreds of educators interested in teaching the subject of genocide. The following year, we did the same thing in Baltimore, Md., also through a generous grant from the Armenian Youth Foundation. It was there where I met Ron, the author and developer of this curriculum.

Over the last 10 years, Ron has not only graciously volunteered his time to help author the Armenian Genocide curriculum, but has also worked on a curriculum on the Pontian Greek Genocide. Although he is very humble about his work, he is a missionary to our cause.

We were also very fortunate to have an active collective partnership with the Genocide Education Project and the NEF, most notably Sara Cohan, Pauline Getzoyan, Roxanne Makasdjian, and Shant Mardirossian. I would also like to give a very special recognition to Molly Sullivan, who helped with the final details in making this curriculum really come together.

Also, the Armenian Youth Foundation was once again instrumental in helping to fund the reproduction of these curriculum guides, which will be available for educators throughout the nation.

Whenever working on something like this, historical content and accuracy is so important. We could not have had a better team to work and review this curriculum every step of the way.

Knights of Columbus of Rochester, N.Y. collect a ‘mountain of clothes’ for Near East Relief in 1923 (Photo: Near East Foundation)

R.J.: What was the process of creating the curriculum? How did you decide what to include?

R.L.: Early on we decided to create a unit that could serve several functions. First, the unit would supplement an exhibit created by the NEF. Secondly, the curriculum would serve as background information for educators who were unfamiliar with the NER. Finally, the unit would provide teaching materials for those educators interested in incorporating the NER into their American and world history classes.

We decided not to include detailed information on the genocide itself—such as the causes, events, and aftermath—because that would make the unit far too long. We did decide to include the Greeks and Assyrians as well as Armenians, since NER efforts helped all three groups.

When beginning my research, I relied on three resources: Peter Balakian’s Burning Tigris includes a great deal of information regarding how Americans reacted to the genocide. Merrill Peterson’s Starving Armenians concentrates on American relief efforts. Of course, the NEF has a treasure trove of documents, photographs, and posters of the NER. Molly Sullivan, the director and curator of the Near East Relief Historical Society, was a tremendous help in locating and identifying photos and posters we used in the unit. She also is a wonderful editor.

I followed chronologically the development of the NER from its inception in 1915 to its becoming the Near East Foundation in 1930. Of course, the unit discusses the remarkable efforts of many NER workers overseas. However, we also wanted to emphasize the widespread support for the NER within the United States. Eventually every state and territory had at least one local branch of the NER.

Something I hadn’t realized when I began my research were the remarkable accomplishments of the women of the NER. In an era when most middle-class women stayed at home to concentrate on their own families, women of the NER continually risked their lives against overwhelming odds to protect and assist refugees, especially orphans. And a surprising number of these women were in positions of authority, for example, as doctors running clinics. These women courageously bore witness to the genocide, even as their own government tried to downplay these massacres in order to get along better with the new Turkish government.

R.J.: What were some of the challenges you faced while drafting the curriculum?

R.L.: There were several challenges in drafting the curriculum. There’s always the question of historical accuracy. For example, scholars don’t always agree on statistics (that is, number killed). We did have some historians vet the material.

We wanted this to be a unit on the Near East Relief, not on the entire genocide. We had to include enough background to help the reader/student understand what was going on within the Ottoman Empire, but not too much to make the unit unwieldy. We do include a list of excellent classroom resources on the Armenian and Greek Genocides.

We wanted to incorporate something of the Greek experience during this genocide. The NER helped Greek refugees tremendously, especially after World War I when the new Turkish government committed atrocities against the Greeks in the Pontus (Black Sea) region and Smyrna. Again, we had lots of discussion regarding how much to include.

The NEF has so many photos and posters that we had a difficult time selecting what would best illustrate the narrative of the lesson. Again, Molly Sullivan of NEF was a superb resource.

Finally, the layout had to be eye-catching and interesting. Fortunately, we had a professional graphics design firm help. We had quite a few people involved, from the West Coast to East Coast and in-between. That was helpful in that it brought a variety of experience and perspectives to the unit. Of course, with so many cooks in the kitchen, it tended to slow the process, but the final results are worth the delay.

R.J.: What do you hope this project will achieve? What are the next steps to insure that schools will incorporate lessons on the Near East Relief in their American or world history classes?

K.S.: With the curriculum completed, the next step will be to have it not only in print, but also on both the Genocide Education Project’s and NEF’s websites. We are also in the planning stages to organize workshops in various cities from coast to coast in the coming 2015-16 school year.

Currently, close to a dozen states mandate the teaching of genocide in their curriculum, and we will work to have this curriculum available to them.

One other unique component to this is the NEF’s traveling exhibit, “They Shall Not Perish: The Story of Near East Relief.” We will work to utilize the traveling exhibit in conjunction with the teacher’s workshops we host in the fall.

The post Teaching Genocide Prevention through the Story of Near East Relief appeared first on Armenian Weekly.