The Armenian Weekly Magazine

April 2015: A Century of Resistance

Approximately 65,000 people identified Armenian as their mother tongue in the 1927 Turkish census. Just over 77,000 professed Armenian Apostolic as their religion. Geographic breakdown is the only additional detail contained in the census, with 70 percent of the stated Armenians living in Istanbul. Outside of Istanbul, those listing Armenian as a religion would occasionally outnumber Armenian speakers, and vice versa. If one assumes the number of Armenians as being the higher of the two by geographic region, the total number of Armenians would be slightly more than 80,000 and the proportion outside Istanbul increases to approximately 35 percent.

The 1935 Turkish census supplies slightly more information. Mother tongue is further divided into second language spoken. In addition, religion by mother tongue is detailed. Interestingly, there were separate classifications for Gregorian and Armenian within religion.

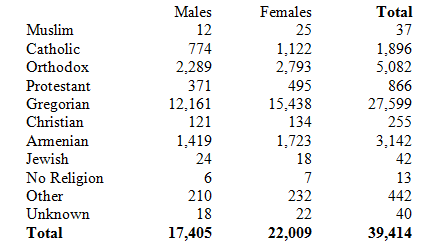

In Istanbul, the number of people professing either Armenian or Gregorian as their religion dropped from more than 53,000 in 1927 to 48,537 in 1935. The following table details the religions of those who listed Armenian as their mother tongue.

Istanbul 1935: Armenian as Mother Tongue

More than 8,000 Armenian speakers listed a religion other than Armenian Apostolic. If we add this number to those professing Armenian Apostolic, the total would be more than 57,000. Presumably then, 15 percent of the Armenians of Istanbul did not profess to be Armenian Apostolic. The greatest number of these professed to be Orthodox. It could simply be that through marriage some Armenians accepted Greek Orthodoxy. Similarly, approximately 200 Greek speakers professed to be Armenian Apostolic. Or it could be that some Armenians simply considered Armenian Apostolic as an Orthodox faith for census purposes.

Finally, approximately 4,800 people professed Armenian as their second language. There is no way to discern how many of these have already been accounted for, but it is assumed that most, if not all, are included with non-Armenian speakers classified as Armenian Apostolic.

All of this assumes accurate reporting by the population. “Hidden Armenians” have documented a fear of census takers in their accounts. Clearly, experience would have made most people cautious about self-identifying as Armenians, particularly in the more remote areas of the traditional Armenian homeland. For instance, no Armenian speakers or people professing an Armenian religion were recorded in the Van province in 1927 and only a handful of businessmen were recorded in 1935. Yet, published studies, as well as my own personal experience, indicate that there are many areas of Van where even today descendents of Armenians live. For example, while traveling in the region of Shadakh last year, I met numerous people who stated they had a grandparent that was Armenian.

With the passage of time, the remnants of the Armenian community were assimilated or blended with the much larger Muslim population. The educational system, as well as mandatory military service, contributed to assimilation along with economic and cultural pressures. The district of Beshiri possibly offers an interesting example of assimilation.

In 1927, 1,585 Armenian Apostolics were recorded in the Siirt province; of these, 1,369 were in the Beshiri district, though only 67 were Armenian speakers. While the districts within the Siirt province had changed by 1935 (e.g., Sasun/Sassoun was moved to the Mush province), Beshiri, where most of the recorded Armenians had been in 1927, was still part of the province. The total population of Beshiri grew from 13,000 to more than 16,000 by 1935; yet, the Armenian Apostolic population was recorded as only 70 in the entire Siirt province. The number of Armenian speakers was only 161, and an additional 146 had Armenian listed as a second language. So what happened to the 1,400 Armenians of Beshiri in those 7 years? Interestingly, while in 1927 the number of Apostolic Armenians far outpaced the number of Armenian speakers, the relationship reversed in 1935.

The growth in the population of Beshiri actually outpaced the rest of the province, so there is no indication that a large number had moved. However, in interviewing an Armenian whose family had come from Beshiri, it was learned that in 1929 there were clashes between the Kurds and Armenians and that some of the Armenians had left for Kamishli. Those that did not move clearly would have had incentive to hide their Armenian identity.

If we think of the great-grandchildren of the 1,400 Armenians of Beshiri, they would be between 100 and 12.5 percent (or 1/8th) Armenian, depending on the rate of intermarriage. In 1927, per the official census, 10.5 percent of the Beshiri district was Armenian. As of the 2000 census, the population of the Beshiri district was 33,106. Ignoring migration and differences in fertility and mortality rates, anywhere from 3,500 to 27,000 of these people could be descended from the original 1,400 Armenians.

Beshiri is not unique as an example.

The point of this detailed analysis is that we simply cannot know, with any reasonable accuracy, the number of Armenians in Turkey, much less those that are “hidden” or Islamized. No matter how much the calculations are further refined, they will not lead to a more accurate estimate. The above analysis, though, does explain why those who make such estimates often state widely varying numbers. What we do have is anecdotal evidence of the existence of large numbers of Armenians still living in the traditional Armenian homeland, and of what they endured in the 100 years since the genocide.

There are stories of conversions to Islam, of pressure to leave homes, of relatives lost and found.

Years ago, I met a group of men from my grandfather’s village at the church of Sourp Kevork in Istanbul. The village of Burunkishla was in the Boghazliyan district of Yozgat, and after the genocide many survivors from that region came together in the village. These men told of Muslim refugees from the Balkans coming to Burunkishla in the 1930’s, leading the remaining Armenians to gradually move to Istanbul and other places. In the 1990’s, I believe only one Armenian still retained property in Burunkishla.

Recently, while in Diyarbakir, in the courtyard of Sourp Giragos, I met a man from Istanbul whose family was also from Burunkishla. He supplied more detail to the story of the Muslims refugees. It was not simply that they had moved into the village; the government had demanded that each household supply rooms to these refugees. You can imagine the resulting strain of such an arrangement. I have read similar accounts from other towns as well, and it is clear that every effort was made to make the Armenians feel unwelcome in their own homes.

This pattern of discrimination, lack of security, etc., has continued uninterrupted for 100 years and has led to those remaining Armenians to either leave or borough further into hiding.

The most well-known account is Fethiye Çetin’s moving book about her grandmother. It can be viewed as marking the beginning of the current era for Hidden Armenians—a period of public recognition. The Hrant Dink Foundation is at the forefront of publicizing their stories, through conferences and books. Each account has significance.

In one account, a man discusses his grandparents: “This power of human beings to endure is beyond my understanding. Your three children are killed in front of your wife and your neighbors know about it. Then you go on living in the same town and give birth to other children. … I was never able to understand this.” Of course, oftentimes, the survivors had to not only live in the same town with the killers but live in the same household.

Thus, you have this intimidation that fosters the suppression of Armenian identity. The process of the genocide itself taught those who survived to remain hidden throughout their lives. Those who believed in periods of safety and increased rights would find that soon the atmosphere had changed and those who exposed themselves as Armenian suffered. Even the opening that presumably exists today is viewed with suspicion by untold thousands of Hidden Armenians.

A couple of years ago, we were in a village in the region of Moks and a man we were talking to said that there was an elderly Armenian woman in the village. He said that she was too ill for us to meet, but that her son was working in the field nearby. We found the man and inquired about his mother. He confirmed that she was indeed too elderly and sick for visitors, but in any event she was not Armenian. He claimed the other man had said she was Armenian because he had something against them. These feelings of insecurity thus linger, along with the need to deny one’s identity.

For many, there is also the perception of Armenian as a religion, not an ethnicity. Thus, the conversion to Islam marks a break with their family’s Armenian identity.

The rupture of family relationships is particularly emotional. Those that speak of their Armenian origins universally speak of lost relatives: the last saddle maker of Mezereh, the last Armenian of Chungush, a family from Sakrat. The sadness of loss, the desperation and hope in their eyes haunts me.

One account from Mush speaks of a father, a priest, being killed and the murderer taking his wife as his own. The priest had two children, a boy, age five, and a girl, three. The murderer decides only to keep the boy and throws the girl out of the house. For the rest of his life, the boy searched for his lost sister in vain.

In 1915, in a small village in Palu, there was a family of seven—a mother and father and five daughters. The father was decapitated and his body left by the river. One daughter was forced to marry a Turk in an effort to save her infant son, but the son was murdered anyway. Another daughter was taken by a Muslim family, yet cried so much that she was taken to an orphanage where she died of starvation. Two of the daughters, one an infant and the other age 17, were sent with their mother on the death march, never to be heard from again. The last daughter was taken as a slave to a Turkish family and lived that way for six years before being rescued. She was my grandmother. Each time I travel to those lands, it is with the hope that I will someday meet the descendents of my grandmother’s lost sisters.

I have joined the Armenian DNA Project in hopes that some day, one of the descendents of those lost girls will by chance also take a DNA test and we will find each other.

Until today, Armenians taken during the genocide were counted in the column of deaths. Even those who were taken considered themselves dead to their surviving family, which had managed to survive and escape. There is the story of Karnig Mekredijian, who had survived to form a family in Beirut. Yet, he still thought of his mother trapped in Kharpert. In the 1960’s, Karnig sent his wife to Kharpert to rescue his mother and bring her to Beirut. Her response was heartbreaking: “Look at my appearance, how I am dressed. It’s very difficult at my age to change and start a new life. I am dead for my kids over there, while here I have also a family, with a husband, kids, and grandchildren…”

We cannot change the victimization. The victims still exist. But to me, allowing the identity to blossom in each Hidden Armenian is to reduce the 1.5 million deaths.

I have stated this previously, but I can think of no better way to end. The Hidden Armenians must be welcomed back to their Armenian heritage. Not as second-class citizens, not to move from one discrimination to another, not to be viewed as less. They are thirsting for it! Each one is a precious miracle of surviving identity and is the key to the return of an Armenian presence on our homeland. Armenian culture and heritage was born of that land, and after 1,000 years of assimilation and purposeful destruction, we demand the right of its return.

This article appeared in the Armenian Weekly’s April 2015 Centennial magazine.

The post The Armenian Key to the Homeland appeared first on Armenian Weekly.