Special for the Armenian Weekly

ISTANBUL (A.W.)—On April 24, 2015, Armenians from all over the world converged in Istanbul to commemorate the Centennial of the Armenian Genocide. In the sea of people, Sevag Balıkçı’s portrait loomed overhead. Who was this young Armenian soldier killed during his military service four years ago, on April 24, 2011?

A Century after the Genocide

On April 24, 2015, the sun rose on Istanbul just like any other day. In Kadikoÿ, in the Asian part of the city, the streets were quiet. Shops were open and people were eating breakfast outside. It seemed as though everyone had chosen the same dish: a big white plate with cucumbers, greens, tomatoes, ham, cheese, and olives, and another plate with little compartments filled with jelly, butter, Nutella, and, in the middle, a boiled egg. I grabbed a quick bite and walked to the ferry station to get to the European side of Istanbul. I took the ferry heading in the direction of Eminönü. On the boat, waiters walked around with silver trays, offering orange juice, tea, and paninis to people on board. For 2 Turkish liras—not even $1.50—we could enjoy an apple tea while watching the landscape along the Bosporus.

When I arrived in Eminönü, I could see that we had to walk through a tunnel to get to the other side of the road and into the city. I followed the crowd, past little kids asking for money or selling things. I wondered who they were; someone would later tell me that they were Syrian refugees. In the spice bazaar, I wanted to stop and admire all of the colors in those little stores. But the streets were too small and the crowd was too big. And I needed to move fast. I had to be somewhere in less than 15 minutes.

For the inhabitants of Istanbul, April 24 is a day just like any other. But it is a symbolic day for the more than 40,000 Armenians who live there. This April 24, Armenians the world over united to commemorate the Armenian Genocide Centennial. Politicians headed to Yerevan. But for many Armenians, Istanbul was the place to be. At 11 a.m., the first event of the day took place in front of the Islamic and Turkish Arts Museum. One hundred years before, on April 24, 1915, this had been the Central Prison where 250 Armenian intellectuals were rounded up before being taken to the Haydarpasa Train Station, and then sent to their deaths.

Around 300 people were present this April 24 to commemorate the memory of the intellectuals. Arkan, 28, is Turkish. He was at the demonstration for one reason: “It is important to recognize the genocide of the Armenians. My whole life, it was like a subject we couldn’t talk about. I think it is our responsibility to show some solidarity. We did it. My ancestors did it. And since the genocide is not recognized, I feel ashamed. And until it is recognized, I will be [here]… All Turks should be [here] too.”

This is a feeling shared by human rights lawyer Eren Keskin. “We are the grandchildren of the perpetrators of genocide,” she said. “Perhaps not each and every one of us comes from the lineage of the people who directly participated in the massacres…but we were born into their ethnic and religious identity. We belong to a social group that has unquestioningly benefited from the order and privileges created by the perpetrators of the genocide.”

Hovhannes lives and works in Istanbul. As an Armenian, being in front of this prison is more than symbolic. “It is where it all started. We had to be here,” he told me.

One activist read a statement at the demonstration—“What we are speaking of here is a crime lasting 100 years. A denial lasting 100 years…”—that was signed by Anadolou Kultur; the Human Rights Association; the Committee Against Racism and Discrimination; Nor Zartonk; the Platform for Confronting History; the Turabdin Assyrians Platform; and the Zan Foundation for Social, Political, and Economic Research.

Some people wore a pin or a T-shirt with the design of the forget-me-not flower, and the words “Project 2015.” Inna is 25, and she came from Ankara. “I’ve been waiting a long time to wear this badge here in Istanbul. This flower means lots of things, but the most important for us is: ‘Don’t forget me.’ We will never forget,” she told me.

Many demonstrators held up portraits of the arrested intellectuals of 1915: Daniel Varoujan, Krikor Zohrab, Hagop Terzian, Roupen Zartarian… And in the middle of these old pictures, one was more recent than the others. It bore the words: “SEVAG, unutturmayacağız,” which translates to “Sevag, we won’t forget you.” Sevag Balıkçı was a young Armenian soldier who was killed on April 24, 2011, during his military service in the Turkish Army.

On the way to the ferry, to go to the next step of the commemoration, Benoît Marquaille, Regional Council of the Ile-de-France region, expressed his commitment to the recognition of the genocide. “I came with Benjamin Abtan, president of the Anti-racist European Movement. They are doing such an amazing job. I think I am the only French politician here today because they are all in Yerevan for the commemoration. It is symbolic to be here in Istanbul. It is where everything started. It is here that everything has to be played,” he said.

After 30 minutes on the boat, we got off at the Haydarpasa Train Station. As we had witnessed in front of the museum, people stood up in front of the station holding portraits of victims of the genocide, as well as signs that read, “This building is a crime scene,” “Genocide! Compensate!” and “Genocide! Recognize!” Some also came with portraits of their ancestors or with a red flower with the names of the intellectuals who were arrested and later killed. The train station is on the Asian side of Istanbul. The intellectuals were taken there to be deported to their deaths. And still, in the middle of the crowd, Sevag’s face stared back.

A demonstrator holds a poster of Sevag’s face and the words, ‘Sevag, we won’t forget you.’ (Photo: Elsa Landard)

At the end of the day, Istiklal Street, the longest street in Istanbul near Taksim Square, was filled with protesters, still holding pictures of the intellectuals and other victims of the genocide. They shouted slogans calling for unity, marking this day as only the beginning, and vowing to continue the struggle for recognition. Demonstrations are usually forbidden in Taksim Square, but Nesrin Goksungur, who is my translator, says the police can’t do anything in front of the French Consulate. “France recognized the genocide. In front of the consulate, we are normally safe. Normally. When there is a demonstration here, usually the police let it happen for about half an hour, just to let people say what they have to say. But after, we have to scatter. If we don’t, the police could intervene, and it won’t be fun,” she explained.

Turkish and Armenian songs were heard during the evening demonstration. Between the speeches, we could hear noise coming from the streets behind. No one around me could say with certainty if the approaching noise was coming from ultranationalist protesters. In fact, earlier that day, ultranationalists had held speeches in front of the French Consulate claiming that the Turks did not commit genocide, that they defended their native land.

Yervart Danzikyan, the editor in chief of Agos, told the Armenian Weekly that black flowers had been placed in front of the newspaper’s offices that very same day. “Being an Armenian journalist and especially writing about this issue is not easy. Sometimes, we can be fearful, but if there is no hope there is no life. So we hope things are going to change,” he said.

And everywhere along Istiklal Street, we still see Sevag’s portrait.

Who Was Sevag?

I am in a cab with my translator, Nesrin. Martin, who will record the interview, and Elsa, who will photograph, are also with us. Nesrin is on the phone with Ani Balıkçı, Sevag’s mother. The driver decided to drop us off early; thankfully, we are on the right street, but not the right number. Ani tells us where to go. Walking down this street, we can see a woman, wearing black clothes, on the phone on the terrace of an apartment building. Located on a quiet street of Kadıköy, the Balıkçıs’ apartment is on the last floor of the building. Ani motions to us to come up. She welcomes us. As do her cat and her dog. Nesrin is not very comfortable since she is afraid of cats and dogs—very ironic in a city where cats are everywhere and are often cherished. Ani reassures her: “We took him in because he was crying on the street. But I don’t like the cat hair.” Ani invites us to take a seat around her living room table. She sits. Behind her, a portrait of Sevag is on the mantel. Ani takes a deep breath. She knows I want her to tell me about her son.

On April 1, 1986, Ani Balıkçı is taken to the hospital. She is 7 months and 2 weeks pregnant. She and Garabet (Garbis), her husband, think they still have time before the birth of their son. However, she delivers the child early. She names him Sevag. The name is a tribute to Roupen Sevag, the famous Armenian poet who was arrested on April 24, 1915, and later executed. It is also a tribute to Sevag’s eyes, as “sev ag” means “black eyes” in Armenian.

After 20 days of hospitalization, the steep hospital bills weigh on Ani. Her son is in stable condition, and she wants to go home. The doctors insist that she stay. The hygiene of the premature infant is important, they say. They fear for the baby. Ani is a teacher in an Armenian school. She has to be present for an event she has organized with her pupils. April 23 is a holiday in Turkey: National Sovereignty and Children’s Day. Every year on that day, Turks mark the birth of the Turkish Republic. Children are at the center of this event, and speeches are delivered in schools. Ani remembers the long weeks of preparation: “I thought I still had weeks before delivering my baby. I had prepared the celebrations with my pupils. I could not miss it.”

Even though Ani was a teacher in an Armenian school, the event was compulsory. In Istanbul, around 3,000 Armenian students attend 16 Armenian schools. Teachers work hard to keep the Armenian language and culture alive. But students must follow the Turkish school program. Armenian children live between two cultures, and the Turkish one is dominant. But Ani loves to teach and to pass on her values. On April 23, 1986, she leaves Sevag home with his grandmother. The celebration goes well as planned, but the following day, on April 24, 1986, Sevag turns purple. Ani has to call the doctor and bring Sevag to the hospital. His lips are blue, his life in danger. Doctors don’t have any hope and tell Ani she should be prepared to lose him. That same day, Sevag’s heart stops beating. “A few minutes after they told me this, we heard the sound of a baby. It was Sevag. I’ve never felt so happy in my entire life. How could I know that I would lose him the exact same day, 25 years later?” she asks.

Sevag is a good child; he smiles a lot. He is also close to his sister, Lerna, who is like a second mother to him. He is roguish and full of joy and life. He loves to smile when people point the camera at him. He is also very sociable. The Balıkçıs are a normal family. And like in other families, meals are occasions to talk about neighbors or acquaintances. The Balıkçıs sometimes talk about people they don’t appreciate. Sevag, on the other hand, eats and listens but remains disinterested in these conversations Unlike his friends, Sevag does not like to fight. He is against violence. Except once. “I’d never seen him get into a fight with his friends. But one time, he came back home with his clothes completely torn. I asked him what happened and he told me that he had a fight to defend a girl that others had offended,” Ani remembers.

One day the Balıkçıs go on vacation in Cappadocia. This area in the center of Turkey is protected as a World Heritage Site. It is a volcanic region with rock formations called “fairy chimneys” that were sculpted by the wind, and dot the landscape. The subterranean cities are everywhere. Centuries ago, men dug in the rock to protect themselves from potential invasion.

Sevag is 8 years old when he discovers this area. He has a revelation when he sees the ceramics produced in the region: When he is older, he will become a ceramist. Fascinated by the arts, he decides to study plastic arts in high school, and then ceramic art in college. When he is a teenager, he makes a sculpture. His parents are very proud and display his art in the street. The sculpture disappears, though, and no one knows where it ended up. The Balıkçıs keep a picture of Sevag with his sculpture—it is precious for them.

Sevag loves to walk. During the summer, his family goes to the Prince Islands—more specifically, the Kınalıada Island, the fourth biggest island of the Prince Islands. The family spends their vacations there, where cars and other motor vehicles are forbidden.

When he is in Istanbul, Sevag likes to walk in Kadıköy, and more particularly in Moda. “After his death, we found Sevag’s pictures. Most of them were taken in Kadıköy,” says Ani. This district is located in the Asian part of Istanbul, and has become a cultural hub. Kadıköy’s center has many car-free streets. Simit sellers are everywhere, as are fresh juice sellers. Even if they are common in Istanbul, they make Kadıköy seem like a village, unlike the European part of the city where crowds are constantly present. The center of the district welcomes artists, writers, and second-hand booksellers. Soccer-lovers go to this area when there is a game at the Fernerbahçe Stadium. The area also has a reputation of being more liberal. It is where students like to go out, where people from all over the world like to live. In Moda, the parks offer a view to the Marmara Sea. There are many playgrounds for children. Along the walkway, couples sit looking at the sea.

Ani Balıkçı looks at photographs of her son in what was intended to be his bedroom in their new home (Photo: Elsa Landard)

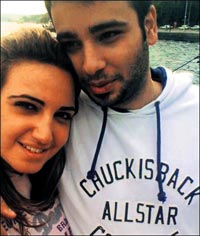

It is here that Sevag likes to walk with his girlfriend, Melani Kumruyan. Sevag wants to marry her. He has a ring for her. He likes this area so much that his parents decide to move to there while Sevag does his military service. They know their son will be very pleased by this. They even set up a room for him.

Sevag’s room is bright. The walls are white. One bed is set up on the right corner of the room, in front of the door. At the bed end, there is a little table made of wood and glass. There is a soccer cup, shaped like a plate. Next to the table, there is a piece of furniture, built in the shape of a glass bottle. Ani is proud: “Sevag made this.” His pictures are everywhere in the room. We can see his baptism, but also Sevag with his friends and family. Ani smiles as she looks at a picture of her dancing with Sevag. But Sevag never saw his bedroom. He died 20 days after his parents moved here.

A Deliberate Execution?

Sevag starts his military service in February 2010. His family tries to convince him to change his mind. If he signs up for another year of school, he could postpone his compulsory military service. In fact, the military service has to be completed before a person’s 38th birthday. At that time, in 2010, military service lasted 15 months—nowadays, it ends after 12. But in Turkey, men who have not completed their military service can’t do much else: They can’t get married; they can’t have a job. Military service is written on CVs, and is, almost always, a condition for employment. Being exempted is also not a good option. In fact, those who are exempted are called “kurut” in Turkish, which means “rotten.” The “kurut” are, for example, homosexuals. Homosexuality is not forbidden in Turkey, but it is considered a psychosexual disorder. Conscientious objection is not a good idea either, because it is considered as a crime for which you can go to jail. Ani remembers when she tried to convince him: “I told him to register at a college again, but he answered ‘I am sick of it. I want to do it, to end it, and I’ll be all set for the rest of my life.”

Military service has two parts. First, there is the learning portion. Sevag is sent to Bilejik, in the west of Turkey. When he takes the uniform, the army gives him a gun. Ani remembers their first phone call: “He told me, ‘Mum, they gave me a gun. What am I going to do with a gun?’” Ani tries to reassure him, telling him that he probably won’t have to use it. Even when he was a kid, Sevag never played with guns. “He neither liked weapons, nor the army. He has been raised in an anti-military way. He never had any plastic weapons as toys.”

After some time, Sevag is sent to the Batman area, in the southeast of the country, less than 100 kilometers from the Syrian border. The area is dangerous mainly because of the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) who claim the area. Kurdish identity is rejected, the Kurdish language is forbidden. The Turkish Army bombards them, and the PKK strikes back. One more time, Sevag’s family asks him to request a transfer to somewhere else. But Sevag does not want to. In Batman, he can make phone calls, which is not the case in all the bases. He asks his mother to send him colorful clothes since he dislikes the army uniform. Ani smiles as she remembers how happy Sevag was when he received his clothes. He calls often but does not tell his parents what’s really going on at the base.

Nothing makes them think that things are going wrong with the other soldiers. Pictures show Sevag on good terms with the others, even with the man who shot him. But some incidents worried the family. Sevag’s father, Garbis, has to go to the Batman base. Sevag was beaten by non-commissioned officers. One soldier said that Sevag stole from him. Garbis wants to protect his son, and tells Sevag they will pay for the missing items. Sevag is angry. Ani explains: “He was very angry. He said, ‘I don’t want us to pay for something I did not do.’” Sevag protects his parents from the truth; he just talks to his girlfriend. She tells Ani and Garbis that at Sevag’s base, there are fascists and ultra-nationalists.

The army claims Sevag’s death was an accident. But the “accident” occurred on April 24, 2011, the day of commemoration of the Armenian Genocide. Coincidence or not, the family and the Armenian community have doubts regarding the army’s explanation.

Ani asks if she can light a cigarette. I can feel that talking about her son brings forth many emotions. She tries to channel them. Tears are coming. She looks at the large glass of water in front of her, and takes a minute. She is going to tell me the day she learned about Sevag’s death.

April 24, 2011: It is a Sunday. The Balıkçıs are ready to celebrate Easter. They are not very religious but Garbis likes to go to church sometimes. This day is also the 96th commemoration of the Armenian Genocide. It is a symbolic day and a double occasion for Sevag’s father to go to church. On Easter morning, Ani calls Sevag to remind him that today, it is a holiday. Sevag asks if she can send him some pastries. Ani remembers: “I used around 7 kilograms of flour to make as much cake as I could.” She wants to please Sevag, but also the other soldiers of his unit. Sevag asks for clothes. He specifically wants white clothes. The post office is not too far from the apartment. Ani prepares the package and mails it to him. She wants her son to receive it as soon as possible. He only has around 20 more days to spend in the army before coming back home. Ani knows that very soon, he will be home and that he can eat as much cake as he wants. He will also go back to work at his father’s jewelry shop, not very far from the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul.

The day moves forward. Garbis is still at church. Ani receives a call. Her husband is calling. He seems worried. He tells her that a friend told him something was written about Sevag on Facebook. He asks Ani to look into it. Ani is not very familiar with social networks. “I wondered how I will find something about it. And I did some [online] search about the Batman area and the military [base] over there. I found a post in which I read that a soldier had been killed while joking with a friend. It was Sevag.” That is how she learned of her son’s death. The army tried to reach her but since the Balıkçıs had recently moved, they did not have time to notify the family. Ani couldn’t believe it. Sevag’s grandmother loses consciousness. She is still at the hospital—she hasn’t been the same since. During the funeral, officers from the Turkish Army are present in the Armenian church of Feriköy, in the Şişli area. Sevag’s coffin is covered with the Turkish flag. For the army, Sevag died a martyr.

Ani can’t talk anymore. Around the table, we can feel the emotion. Everyone is emotional. It was four years ago and I have the sense that it just happened. Ani has tears in her eyes. She asks if we want some coffee. We say yes without thinking about the fact that Turkish coffee is one of the strongest coffees in the world. Ani offers some chocolate to eat with the coffee. Garbis walks into the living room. He sits on the sofa and listens.

Symbol of a Community

When she learns about the death of her son, Ani is in shock. She tells the media that Sevag’s death has nothing to do with the Armenian Genocide. The soldier who killed Sevag was a friend of his. “I regret that. At that time I was in shock, and for me it was impossible to believe that he was killed intentionally. But he died on April 24.”

A week after Sevag passed away, a delegation of officers appears at their doorstep. They say, again, that it was an accident. That Sevag and Kıvanç Ağaoğlu, the shooter, were friends. That the two young men were joking around and that it was a single shot that killed him. This is also the version of the defendant. The army offers to take the family to where the shooting happened. It pays for the trip. Soldiers welcome the Balıkçıs in Batman. After a 15-minute helicopter ride they arrive at the base and meet the soldiers who were present the day of Sevag’s death, including Ağaoğlu. When it happened, Sevag and a few other members of the unit were fixing the fence around their station. They were not supposed to be armed, except for Ağaoğlu who was supposed to protect the unit in case of an attack. The area is on alert. On this day, no officer is present, which is unusual. For Ani, the incident was planned. “There was no officer, only soldiers are witnesses. One of them was shaking when we went over there. He was still afraid.” Ani asked him why he was so fearful. He said that he saw the shooter aim at Sevag. In court, the witness gets cold feet and on the day of the trial changes his story. Sevag’s family is now convinced: Their son was murdered.

The trial begins in the Diyarbakir Military Court, in eastern Turkey, a few weeks after the murder. Ağaoğlu is investigated. The Balıkçıs’ lawyer, Cem Halavurt, through an investigation of Ağaoğlu’s presence on various social media—especially Facebook—shows that he is a supporter of the nationalist politician Muhsin Yazıcıoğlu and of the hit man Abdullah Çatlı, who was responsible for bombing the Armenian Genocide Memorial in Altfortville, France, in 1984. Ağaoğlu’s Facebook page also shows that he is a member of the Great Union Party, an extreme right-wing Islamist political party.

Another fact intrigues the family. During the first hearing on July 24, 2011, a witness declares that Ağaoğlu threatened Sevag, saying, “I’ll kill you fatty.” But the witness later changes his story.

Melani Kumruyan, Sevag’s fiancée, tells the family that Sevag told her more than once that he was being threatened. She says that a soldier told him once, “If there is a war with Armenia, you will be the first I kill.”

Because of witnesses’ unwillingness to come forward, Ağaoğlu is still a free man. The trial went on for three years; at each hearing, Ani and Garbis had to move to a different city. For Ani, this was “a way to make us give up. They wanted us to get tired of it.”

Since April 24, 2011, Sevag has become a symbol for the Armenian community. April 24 is not only the day of the commemoration of the Armenian Genocide, it is also the day a 25-year-old Armenian was killed. It is what Garbis and Ani have been commemorating for the past 4 years now.

“We don’t commemorate April 24 as the day of the genocide, but as the day we lost our son,” says Ani. Last year, the Balıkçıs went to Paris to visit family members. It was on April 24. The French Armenian community was commemorating the genocide. Ani saw many portraits of Sevag held up high by the demonstrators on the Champs-Elysées. She is touched, but asks herself why her son’s picture is in the crowd. She wonders that on every April 24. It is a fate in the middle of history. Sevag’s fate. Between the insights provided by his family and the lack of evidence that continues to obstruct justice, Sevag’s family and the rest of the world will have to wait many more months, or perhaps years, before the truth comes out.

Until then, Ani and Garbis Balıkçı will keep wearing white on every April 24—the color Sevag mentioned when he last asked for new clothes. And every April 24, Sevag’s dark eyes will stare back at them from the crowd of demonstrators. Until justice is done.

The post Remembering Sevag Balıkçı on April 24 in Istanbul appeared first on Armenian Weekly.