WATERTOWN, Mass. (A.W.)—The Armenian Weekly had the opportunity to sit down with His Holiness Aram I of the Holy See of Cilicia on June 2 to discuss issues facing the church and Armenian communities worldwide.

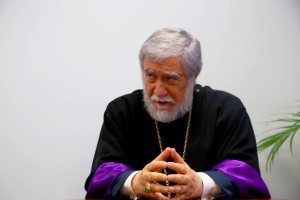

Catholicos Aram I with Armenian Weekly Editor Nanore Barsoumian (left), and Hairenik Weekly Editor Zaven Torikian

During the interview, Aram I discussed the concept of justice—a recurring theme in his public speeches, from Washington, D.C. to Boston—and the role of international law. He also spoke about the lawsuit the Holy See of Cilicia has filed against Turkey to reclaim the historic headquarters of the Sis Catholicosate.

Among other issues discussed was the Syrian crisis; Aram I emphasized the importance of preserving the Syrian-Armenian community, although he acknowledged that the situation is dangerous.

He also discussed women’s rights—specifically the ordination of women into priesthood—and addressed the challenge of remaining relevant in an ever-changing world.

“The church is not a museum. It is a missionary and dynamic reality,” he said.

Aram I arrived in Washington on May 7, and following the Centennial commemorations that took place in the capital, embarked on a pontifical tour of the Armenian communities in the Eastern U.S. He returned to Lebanon on June 4.

Below is the interview in its entirety.

* * *

Nanore Barsoumian—You were recently in Armenia, Rome, and Washington, D.C. What is your general assessment of the Armenian Genocide Centennial commemorations?

Aram I—On a global, pan-Armenian level, the commemorations were well organized. Each community organized the Centennial according to its own environment. My general impression is that not only was it well organized, but the spirit of the Centennial and our objectives were clearly manifested and articulated through these activities. What is most important is not just what we did within the context of the Centennial, but how we should continue the spirit of the Centennial. It is vitally important that we identify the emerging concerns, realities, and priorities, and try to bring them together to develop a common pan-Armenian strategy and vision.

In other words, I don’t consider the Centennial a collection of activities or functions pertaining to [the genocide], but a process. It’s a dynamic process and as such it must go beyond the limits and limitations of the Centennial. That is the message and the challenge of the Centennial.

N.B.—Your message consistently draws on the importance of justice. Please talk about the concept of justice in Christianity, and as it applies to the descendants of genocide survivors today.

Aram I—I have repeatedly reminded our people and the international public that justice is not a human-made concept or reality. Justice is a gift of God. But justice within the context of humanity is not an absolute value in the sense that justice implies accountability and transparency. We should use justice accordingly. That is the meaning of international law.

Justice is a core value that is at the heart of international law. Justice implies accountability from a Christian perspective—accountability to God. From a political perspective, [it implies] accountability to structures and institutions that are engaged in the governance of a given society. Therefore, we need to get justice both from a theological perspective, as well as within the context of political governance.

We cannot govern human societies—or any organization—without justice.

N.B.—Could you talk about the Sis Catholicosate lawsuit within the broader context of justice you spoke of moments ago?

Aram I—A number of international conventions—humanitarian conventions, conventions for the prevention of genocide, the declaration of human rights, and others—together constitute international law. The purpose of international law is to govern societies and states. Justice is there, at the heart of international law.

What concerns the lawsuit, we clearly said that the Catholicosate belongs to the Armenian Church. Due to historical circumstances, the clergy who had lived there for centuries were forced to leave their spiritual house. After 100 years, we think that it is time that we file this lawsuit demanding the return of the Catholicosate.

But let me look at this within a broader context: Almost two years ago, we organized an international conference in Antelias [Lebanon]; the theme of the conference was “From Recognition to Reparation.” That means that after 100 years, we believe that we need to move from recognition to reparation—in other words, from lobbying, from political activities, to the legal field.

Well, it’s not easy, but it is a must in my judgment. I believe that when we speak of justice, we look at it within [the context of] international law. Recognition of the genocide is important, but recognition is not an end in itself. Recognition has clear implications, meaning reparations.

International law uses different terms to define reparation, such as restoration, restitution, and compensation. So reparation is a general framework through which the perpetrator of the genocide—whether the state, the organization, the community, or even a person—should remain accountable.

Now, what do we mean by accountability? That you accept your crime and you take certain actions to repair that. What concerns the Armenian Genocide, we need to start this process of reflecting together as Armenian people. I believe that the state, the political organizations, and our churches should be part of this process. We need to develop a pan-Armenian vision, a pan Armenian strategy in respect to reparations. I think we may have different views, perspectives, and approaches towards what we want from Turkey. We have to bring these perspectives together within a holistic framework and try to develop our common pan-Armenian demands. We have not done so yet.

What concerns the Armenian Genocide, we need to start this process of reflecting together as Armenian people. I believe that the state, the political organizations, and our churches should be part of this process. We need to develop a pan-Armenian vision, a pan Armenian strategy in respect to reparations.

I believe that the lawsuit of the Catholicosate is a first legal action taken in the right direction. Our intention is to open—as far as possible—the legal door which was closed before us for a hundred years. For different reasons, we have not tried to open that door. This will become the first step in a long and complex process. It is not an easy process.

N.B.—The crisis in Syria continues to be worrisome, and it has galvanized Armenians around the world. What is your assessment of the situation in Aleppo? What can the diaspora do?

Aram I—The Syrian crisis is complicated. From the very beginning, we have adopted a clear policy with respect to our Armenian community. We said that we are with the people of Syria—we remain grateful to the people of Syria who received us after the Armenian Genocide and shared their homeland and bread with us. The regimes, the governances are provisional. We should remain attached to the basic perennial values of the people—the people’s power. That was our policy in respect to Syria.

…We are with the people of Syria—we remain grateful to the people of Syria who received us after the Armenian Genocide and shared their homeland and bread with us. The regimes, the governances are provisional. We should remain attached to the basic perennial values of the people—the people’s power.

Secondly, I know that the security situation is extremely unstable—not to say, dangerous. In spite of that, we believe that our community should stay there because the reorganization and revitalization of our community in Syria has a profound importance for our communities in the Middle East, the Armenian cause, and the Armenian people in the diaspora as a whole.

The Middle East is an important region for us. Lebanon and Syria are two very important countries. By all means we have to preserve our community there. That is why we are doing our utmost to help them on social and humanitarian levels.

Some families have left. I understand that. Around 10,000 Armenians are in Lebanon. Less than 10,000 are in Armenia. This is the actual situation in Syria. The most dangerous—I would say, precarious—situation is in Aleppo. We are closely following certain developments in Aleppo. We are trying our best, within the limits of our abilities, to preserve our community in Syria in general, and in Aleppo in particular.

N.B.—Like all churches, the Armenian Church is faced with modern changes today, struggles to be more current on major issues, as well as to reach out to the younger generation. What are some of the ways in which the church is trying to interact with the new realities on the ground?

Aram I—This has been and remains my major concern. I have written on this subject intensively. Today, the renewal of the Armenian Church is a must. Renewal is not just a reformation. The church should become more and more responsive to the emerging realities, to the issues and challenges that we are faced with today in different ways and in different environments.

Our church cannot remain stagnated and self-contained. The church is not a museum. It is a missionary and dynamic reality. The church has to become relevant, credible, intelligible, and acceptable.

Our church cannot remain stagnated and self-contained. The church is not a museum. It is a missionary and dynamic reality. The church has to become relevant, credible, intelligible, and acceptable. In order to do that, the church should constantly and creatively interact with its environment, and with the people. If you ask me whether this is the actual reality of our church, I will say yes to a certain extent. We need more—not only in the U.S. but in different parts of the world.

The church building is a structure; it is not as important. Our ultimate aim should be to have that church building serve to build our community as a church. The church should try to identify with the concerns, expectations, and needs of our people—to try to reorganize its missionary engagement accordingly. Otherwise, the youth will isolate themselves from the life of the church. We need to make our church attractive and relevant in order to attract the young generations.

Our organizations have become petrified and frozen. We are living in a globalized world—the global culture has been attracting our youth. Our organizations should come out of these stagnated and petrified states. In order to become a more dynamic organization, that interaction between the youth and the churches—or our organizations generally—is very important.

N.B.—Now societies in different parts of the world are more accepting to things that they weren’t so accepting of in the past. The church has generally held very traditional values.

Aram I—When you say traditional values, I think we need to differentiate between being traditional and blind. Blind traditionalism is one thing, and constructive and open traditionalism is something else. Tradition is very important. People, communities, structures, and organizations cannot be without traditions pertaining to values, aspirations, objectives, and ways of life. But tradition should keep pace with the rhythm of changing times and realities. We have not yet been able to do that. There are certain attempts and initiatives here and there, but we need more. We need to renew and change our traditions—keep the core and essence, but change the form to become more and more relevant to the new realities and expectations of our peoples.

N.B.—Women’s rights and equality are important issues today. You have, on several occasions, highlighted the importance of giving key roles to women. Even though there are women deacons in the Armenian Church, the church hierarchy is dominated almost exclusively by men, as it is in most churches around the world. What are your thoughts on women’s rights in general, and the church’s role in particular?

Aram I—Our church has been a broad-minded church. We have taken a very moderate, flexible, and comprehensive stand vis-à-vis the critical or controversial issues and challenges that face many societies. What concerns women, from its very inception our Armenian Church has always encouraged the participation of women in the life of the church. In the past, we have had the monasteries for women. We have deaconesses. So in the different spheres of our church, women are there. As I’ve always said, the woman’s place is not in the kitchen; the woman’s place is in our community and church life.

The only issue is women’s ordination into the priesthood. I think we need to discuss this matter. We need to discuss the theological and socio-cultural aspects. My approach is not a categorical one—a “yes” or a “no.” This is a question; and this should remain a question on the agenda of our church, and all the churches. This is an issue. At the proper time, we need to discuss this matter in our common attempt to renew and reform our church.

N.B.—Do you think one day we’ll see a woman Catholicos?

Aram I—The Bible says hope never abandons you.

The post On Justice, Syria, and Women’s Rights: An Interview with Catholicos Aram I appeared first on Armenian Weekly.