Competing Narratives of Suffering

The Armenian Weekly Magazine

April 2015: A Century of Resistance

A global non-governmental and governmental regime has arisen to promote “dialogue,” “reconciliation,” and various “peace processes” among peoples in conflict. I have no abstract objection to any of these terms or practices. In fact, dialogue and negotiation are laudable activities to be used as a means of settling disputes. What I object to are “people-to-people” programs that do not address the power imbalance between communities in conflict, between perpetrators and victims, and do not set as a precondition for their interactions a shared basis in historical truth.

There is government and foundation money to be had in running and participating in these programs, but “dialogue” and “coexistence” efforts have been codified and even industrialized in such a way that they sometimes inflict emotional and political harm on the people they are ostensibly meant to help. What happens when a “dialogue” session devolves into the telling of competing narratives of suffering? What happens when these competing narratives are seen only as individual stories of trauma removed from the political and historical contexts from whence they arose? I believe it is the moral and political duty of all involved to recognize and to address these contexts.

Why Can’t We All Just Get Along?

In the case of the Israeli and Palestinian conflict, the rhetoric of “peaceful coexistence” has often been used to undermine and criminalize Palestinian resistance to Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza and to the discriminatory treatment of Palestinian citizens of Israel. Many Palestinians reject coexistence programs and initiatives because of the way these efforts refuse to acknowledge the vastly unequal underlying power dynamic between the two peoples and in fact “normalize” the system of oppression under which Palestinians live in both Israel and the Occupied Palestinian territories. As an alternative, some Palestinian activists have promoted the idea of “co-resistance.”

Hundreds of Palestinians and Israelis demonstrate at the Qalandia checkpoint in northern Jerusalem in support of Palestinian independence. (Photo: Sheikh Jarrah Solidarity Movement)

Members of anti-occupation, pro-equality Israeli Jewish groups join the ongoing weekly non-violent protests in villages such as Bil’in and Nabi Saleh in the Occupied West Bank. Boycott from Within, a diverse group of citizens of Israel, advocates for the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement in support of Palestinian rights. Sheikh Jarrah Solidarity, a grassroots solidarity movement working towards civil equality in Israel and for an end to the Israeli occupation, was named for a neighborhood in East Jerusalem that is being colonized by violent, right-wing Israeli settlers with the aid of the Israeli government. Sheikh Jarrah Solidarity organized weekly protests between 2010-12 in support of Palestinians who were being evicted from their homes and displaced by Israeli settlers. The photography collective Active Stills, whose members document anti-occupation protests, includes photojournalists who are Israeli, Palestinian, and international.

One hopes that this model of working together can be furthered in Israel and Palestine, as well as replicated in other situations of oppression. With a common analysis of the problems and a mutual commitment to redress, it is possible for people from opposing sides of a conflict to work together for a shared future, not simply a rehearsal of a painful past.

Removing Splinters of Glass with Tweezers

In my own work as a Palestine solidarity activist, I have watched with admiration as members of Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) have labored within their own communities to help undo a false narrative about Israel as “a land without a people for a people without a land.” Many American Jews were taught that the birth of Israel was an experiment in social justice, when in fact that nation-state was founded upon the mass dispossession and ethnic cleansing of its indigenous Palestinian population. Most, if not all, nation-states were predicated upon the rejection, ejection, and erasure of minority and indigenous populations. For example, the United States was created through genocide against American Indians and its wealth was built upon the enslavement of Africans. Modern Turkey was founded through the expulsion of Greeks, the mass murder of Armenians and Assyrians, and the attempted forced assimilation of Kurds.

All nation-states hide these crimes behind nationalist foundation myths that lionize the perpetrators and dehumanize the victims. Citizens are then indoctrinated with these myths that become central to collective and individual identity. Undoing the indoctrination is for many a sad, painful, and lonely experience, but JVP provides a safe and welcoming space in which to do it. I have often thought that the process is akin to someone removing splinters of glass from their skin with a pair of tweezers. Some of these splinters are racist ideas and attitudes that are best examined within the group. Palestinians, for example, should not be held responsible for educating American and Israeli Jews any more than black Americans should feel required to undertake the education of white people who are dealing with their internalized racism.

In my work with the Occupy Wall Street movement here in New York City, I was impressed by the White Allies Working Group, whose main purpose was to educate white Occupy activists so that their often-unexamined assumptions and attitudes would not be a burden to black and other activists of color in the movement. Undoing racist indoctrination—even the kindest variety of liberal racism—is also akin to removing splinters of glass with a pair of tweezers, but there is no reason for people who suffer the consequences of that racism to witness and to share your pain.

Rejecting Dialogue in Favor of Conversation and Co-Resistance

This same principle is at play for me in Turkish-Armenian dialogue efforts. Let the progressive, enlightened Turks—those who have recognized and undone the false narratives about Armenians and the history of the founding of Turkey that they were fed in school and in the mainstream media in Turkey—do the hard work of educating their peers. Once each individual has managed to take apart and cart away the denialist propaganda hindering true communication, then we Armenians can engage in conversation with these like-minded citizens of Turkey. We can further join with them in co-resistance efforts, such as the two that I have been involved with in the past year.

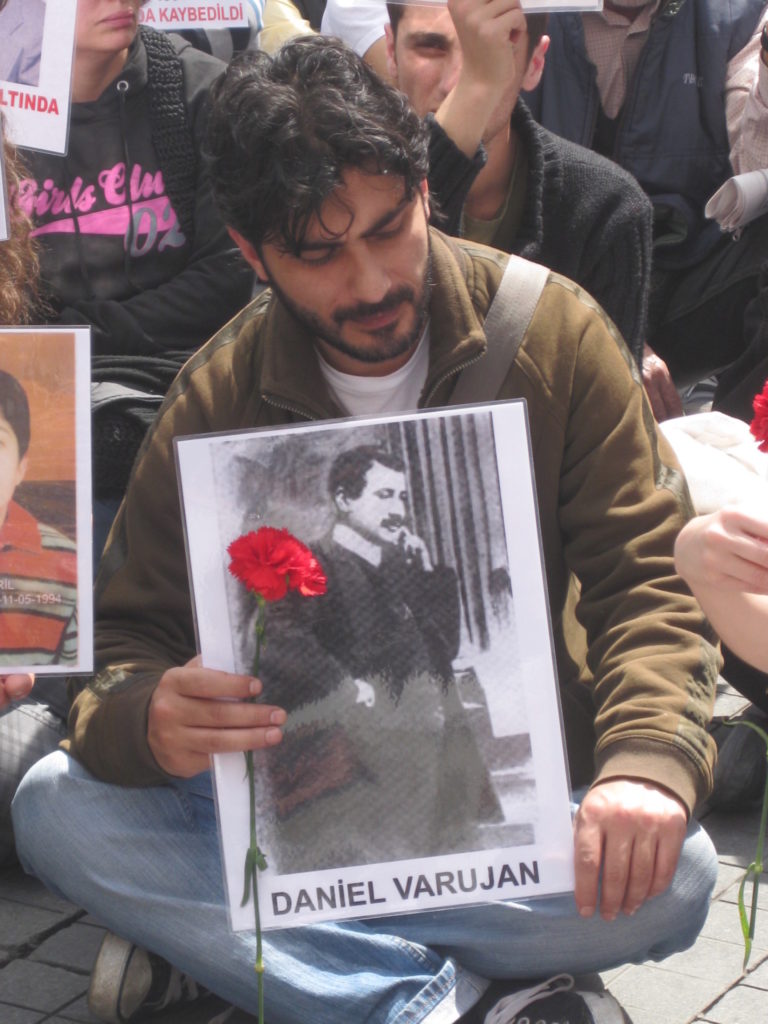

An activist holding poet Daniel Varoujan’s photo at one of the commemoration events in Istanbul. (Photo: Khatchig Mouradian)

In September 2014, I spent a week in Istanbul with a group of feminist academics, artists, and activists as a part of Columbia University’s Women Mobilizing Memory Workshop. Participants were from New York City, Santiago, and Istanbul, and the week was filled with discussions, lectures, and presentations about mass trauma, memorialization, and action for change. The topics we addressed were varied and included the Holocaust, the Pinochet dictatorship, the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center, the Armenian Genocide, the enforced disappearances of Kurds in the 1990’s, and the Dersim Massacre, among others. The Istanbul-based participants without exception used the term genocide in discussing what had happened to the Armenians in the final days of the Ottoman Empire, which was a tremendous relief to me. I didn’t have to “dialogue” or argue to prove what had occurred—we were able to engage in substantive conversations about history, historiography, and possible future amends.

For the past six months, I have been working on Project 2015, an effort to organize a mass fly-in of Armenians to Istanbul for the Centennial Commemoration of the Armenian Genocide. Our board is comprised primarily of Armenian-American scholars and professionals with a few Turkish Americans as well. We have partnered with human rights and civil society activists in Turkey who are helping us to navigate the permitting processes and local politics so that our joint events are respectful and secure. We have received some criticisms from Armenians in the diaspora and in Yerevan, suggesting that we are the “dupes” of our partners in Turkey, or that by going to Istanbul we are offering ourselves like “lambs to the slaughter.” But I firmly believe in the rightness of our efforts and the trustworthiness of our team. I am also committed to standing as a witness against denial and erasure with like-minded citizens of Turkey—Turks, Kurds, Greeks, Jews, Assyrians, and Armenians—as we memorialize the victims and the survivors of the Armenian Genocide. This is co-resistance.

The post Choosing ‘Co-Resistance’ Rather than ‘Turkish-Armenian Dialogue’ appeared first on Armenian Weekly.